Sex, Gender, & Intersectional Analysis

Case Studies

- Science

- Health & Medicine

- Chronic Pain

- Colorectal Cancer

- Covid-19

- De-Gendering the Knee

- Dietary Assessment Method

- Gendered-Related Variables

- Heart Disease in Diverse Populations

- Medical Technology

- Nanomedicine

- Nanotechnology-Based Screening for HPV

- Nutrigenomics

- Osteoporosis Research in Men

- Prescription Drugs

- Systems Biology

- Engineering

- Assistive Technologies for the Elderly

- Domestic Robots

- Extended Virtual Reality

- Facial Recognition

- Gendering Social Robots

- Haptic Technology

- HIV Microbicides

- Inclusive Crash Test Dummies

- Human Thorax Model

- Machine Learning

- Machine Translation

- Making Machines Talk

- Video Games

- Virtual Assistants and Chatbots

- Environment

Systems Biology: Analyzing How Sex and Gender Interact

The Challenge

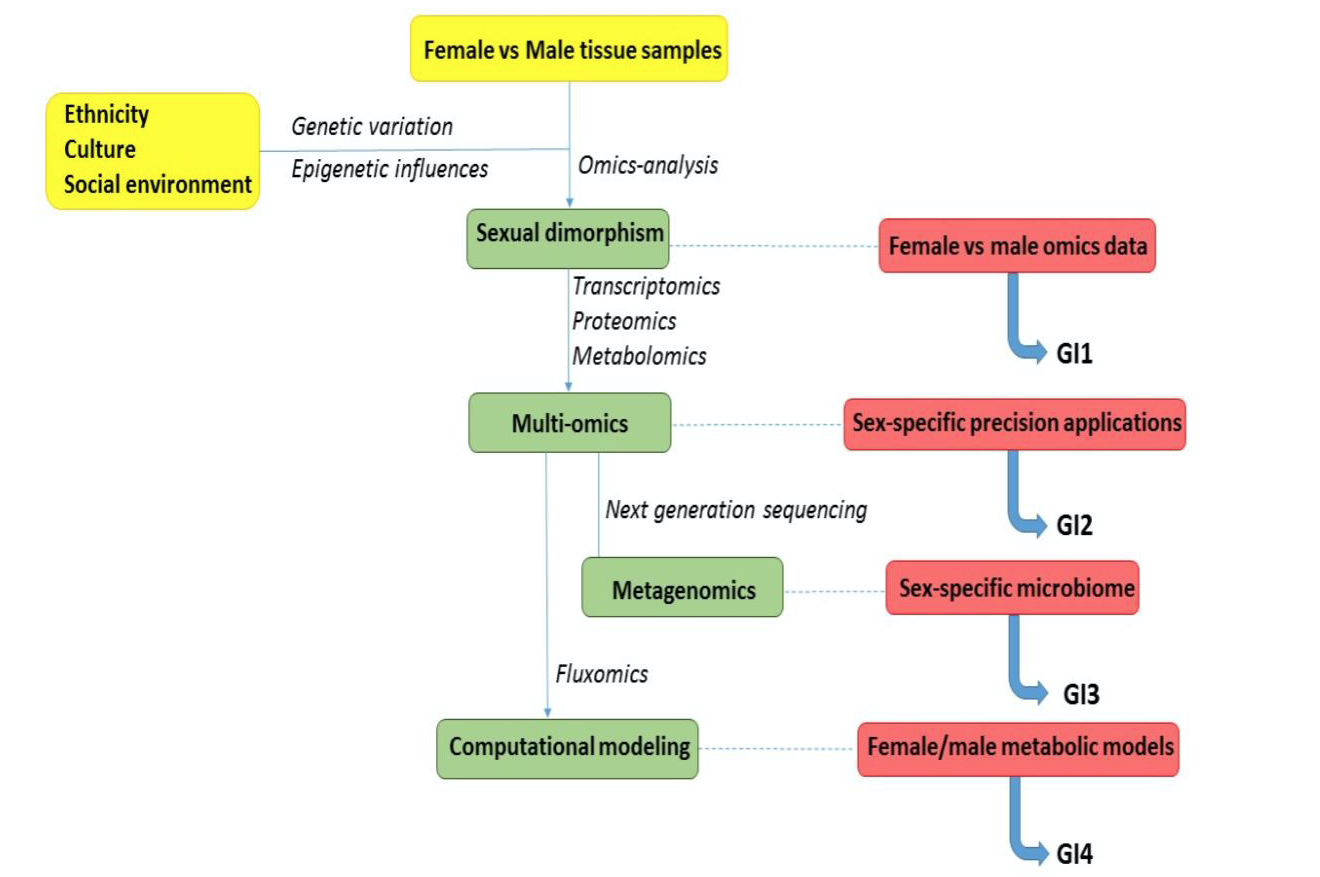

Sex and gender roles can impact the human metabolism. Consequently, prevention and treatment of many non-communicable diseases require a sex-related and gender-related approach. Systems biology is the integrative holistic understanding of biological systems. It is part of what now is referred to as systems medicine and aims to predict individual disease risk and precision treatment by mathematically modeling metabolic processes (Apweiler et al., 2018). Such dynamic models of disease are based largely on omics data (i.e., genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics—Zewde, 2019). Sex bias in the collection of these datasets, however, leads to sex bias in the mathematical models and their predictions.

Methods: Collecting Sex-Specific and Gender-Specific Data

The amount, quality and precision of data have an essential influence on research output. The growing use of large datasets and their integration in fields such as precision medicine, pharmacotherapy and nutrition brings this aspect to the forefront. When collecting information about sex, clear decisions need to be made on how sex is operationalized (e.g. through genomics data alone or in combination with hormonal profiles and phenotype). The same applies to the potential inclusion of gender in these analyses. Currently, the only immediately available option is the collection of data about gender identity. However, as modern biomedical technologies become more refined, information on gender norms and behaviors could also be collected. The integration of this information is the only way to create robust models of disease and generate new personalized therapies or preventative offers.

Gendered Innovations:

1. Collecting data on sexual dimorphism in gene expression improves biological modeling. Accurate biological modeling can be assisted by studies of sexual dimorphism in human gene expression (Labonté et al., 2017). Such studies should also take into account different ethnic, cultural and societal backgrounds, and different lifestyles.

2. Collecting Sex and Gender Data Fuels Integrative Omics. Integrative omics provides a basis for sex-specific precision applications in various fields such as medicine, pharmacotherapy and nutrition. Current datasets under-represent females and under-report participants’ gender identity (Gemmati et al., 2020).

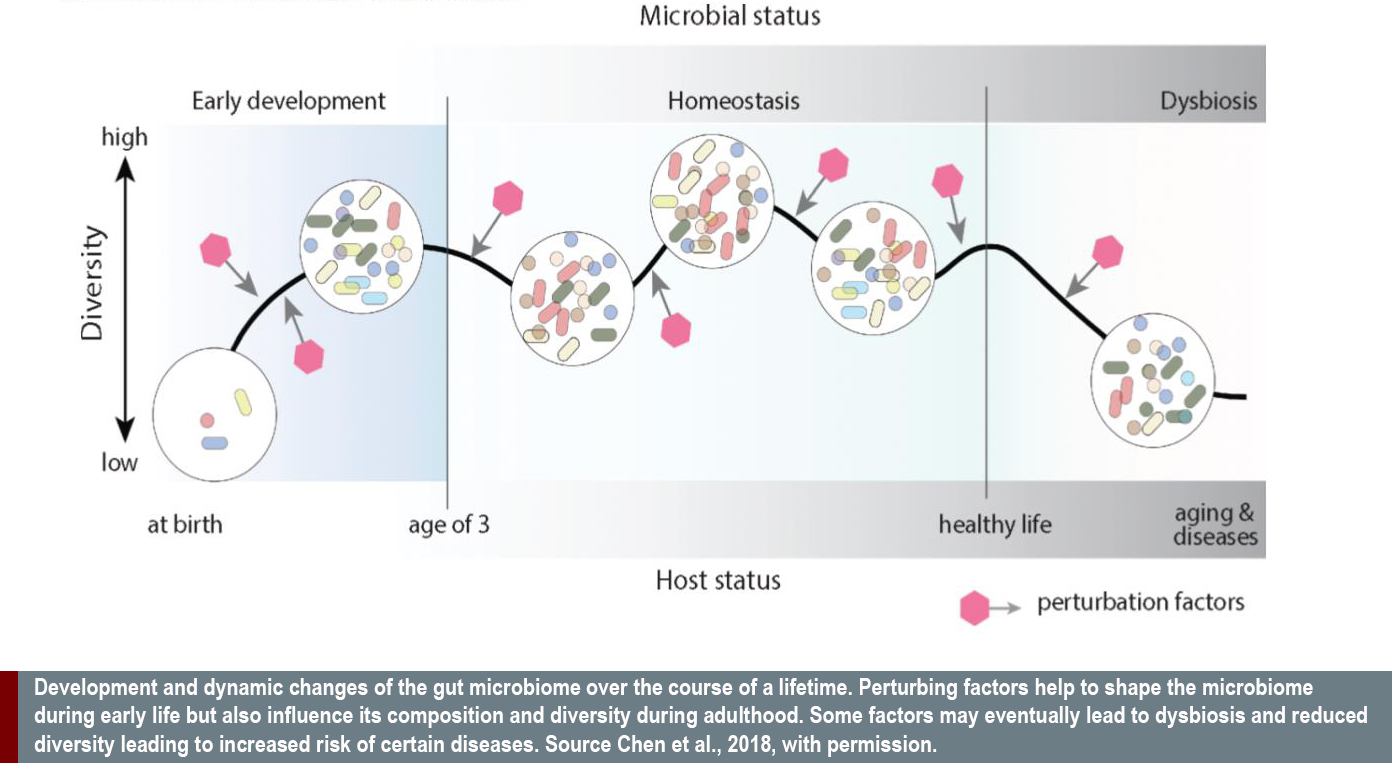

3. Analyzing Sex Improves Understanding of the Role of the Microbiome in Health and Disease. Sex differences are found in the gut microbiome. Analyzing these differences will enhance our understanding of how the microbiome influences the human metabolism and will sharpen our efforts to improve human health.

4. Integrating Sex Difference Improves Systems Biology Models. Researchers and funding agencies have a role to play in correcting sex bias in omics experiments.

The Challenge

Gendered Innovation 1: Collecting Data on Sexual Dimorphism in Gene Expression Improves Biological Modeling

Gendered Innovation 2: Collecting Sex and Gender Data Fuels Integrative Omics

Method: Collecting Sex-Specific and Gender-Specific Data

Gendered Innovation 3: Analyzing Sex Improves Understanding of the Role of the Microbiome in Health and Disease

Gendered Innovations 4: Integrating Sex Difference into Systems Biology Models

Conclusions

Next Steps

The Challenge

It is an interdisciplinary field of study that focuses on complex interactions within biological systems (Tavassoly, Goldfarb, & Iyengar, 2018). Systems biology lets us understand how interactions among multiple components form functional networks at the organism level. For example, Tareen et al. (2019) used systems biology to identify a molecular switch that tissues use to rely either on glucose or on fatty acids as fuel (Tareen et al., 2019). Systems biology also develops predictive computational models of disease that will transform disease taxonomies from phenotypical to molecular and will enable personalized/precision therapeutics (Bielekova, Vodovotz, An, & Hallenbeck, 2014). identity (Gemmati et al., 2020). Systems biologists often use “omics” data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) to provide broad insight into the molecular dynamics that accompany genetic, cultural, ethnic and societal influences on a living organism. For example, a high daily intake of fat (related to cultural and societal factors) has a negative influence on the metabolic performance of tissues in the body and increases the risk of type II diabetes. Systems biologists use omics data to understand a tissue’s metabolic status over time. Since there is sex and gender bias in clinical and omics data (Gemmati et al., 2020), current biological models apply to cisgender men, whereas models of other bodies and genders are under-represented.

Gendered Innovations 1: Collecting Data on Sexual Dimorphism in Gene Expression Improves Biological Modeling

Omics studies of animal organs and body fluids have demonstrated sex differences in biochemistry and the regulation of gene activities. In the liver, for example, over 1000 genes are expressed differently in females and males. Sex differences in metabolic and gene regulatory pathways have also been demonstrated in humans. For example, metabolomic analysis of serum from participants in the German KORA cohort showed significant sex differences in concentration for 102 of 131 examined metabolites (Mittelstrass et al., 2011). Sex-specific Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS) showed that some of these sex differences resulted from genetic differences. Despite these indicative results, most systems biology studies have not considered sex.

Data on human sexual dimorphism are limited. Because biopsy material cannot be taken from many of the organs of living individuals, new strategies need to be designed to intensify studies on sexual dimorphism in genome expression, such as the use of iPSC (induced pluripotent stem cells) or organoids. Ideally, such studies would take into account differences in lifestyle, ethnicity, cultural and social background to incorporate intersectional factors into the data sets.

Gendered Innovation 2: Collecting Sex and Gender Data Fuels Integrative Omics

Integrative omics serves as a foundation for precision medicine, pharmacotherapy and nutrition (Karczewski & Snyder, 2018). Meta-analysis of omics data is a way to find novel diagnostic biomarkers, drug targets or nutritional pathways to prevent the onset of disease. Integrating sex and gender identity into the source data for integrative omics will be an essential first step towards more personalized medicine. Current datasets under-represent females and lack information about participants’ gender identity. Concerning information on the influence of gender identity, in 2018 the gender dysphoria treatment in Sweden (GETS) study was announced to investigate if and how cross-sex hormone treatment to align gender identity with physical appearance leads to metabolic and functional changes including at the genomic and epigenomic levels (Wiik et al., 2018). Big data that includes social and cultural information can open the way to sex-specific and gender-specific precision medicine (Das et al., 2020).

Method: Collecting Sex-Specific and Gender-Specific Data

The amount, quality and precision of data have an essential influence on research output. The growing use of large datasets and their integration in fields such as precision medicine, pharmacotherapy and nutrition brings this aspect to the forefront. When collecting information about sex, clear decisions need to be made on how sex is operationalized (e.g. through genomics data alone or in combination with hormonal profiles and phenotype). The same applies to the potential inclusion of gender in these analyses. Currently, the only immediately available option is the collection of data about gender identity. However, as instruments become more refined, information on gender norms and behaviors could also be collected. The integration of this information could generate new personalized therapies or preventative offers.

Gendered Innovation 3: Analyzing Sex Improves Understanding of the Role of the Microbiome in Health and Disease

Awareness of the gut microbiome’s role in health and disease is growing. Using gene sequencing to construct a Metagenome, researchers can now analyze the composition of the microbiome and quantify the different types of microorganisms present in our gut. The microbiome is influenced by the genetic make-up of the host as well as by cultural and social circumstances. Such sequencing has found women’s and men’s microbiomes differ. Sex differences in the microbiome may not only contribute to sex differences of gut-related diseases, but could also underlie sex differences in neurologic and neurodegenerative disorders (Thion et al., 2018) (H2020-EU.3.1.1. ID:733100, SYSCID). Research has shown that women tend to have microbiomes with significantly higher microbial diversity than men (Chen et al. 2018). The make-up of the microbiome is probably influenced by contraceptives with estrogen, which modify the growth conditions in the gut. Women’s microbiomes display higher resistance to various classes of antibiotics, which seem to follow differences in antibiotics use (Sinha et al., 2019) (H2020-EU.1.1. ID: 715772, BabyVir). These novel observations warrant more profound investigation and may result in sex-specific analysis of health and disease.

Gendered Innovations 4: Integrating Sex Difference into Systems Biology Models

Because biomedical experiments more often use male animals and humans, more data about males than females are available to systems biology researchers. Consequently, mathematical models in biology are based primarily on male data. In order to close this sex gap, journals and granting agencies should promote data collection on females, which is a prerequisite for the generation of female-based models in parallel to the existing male-based models. In addition, available omics data sets are often composed of mixed female and male data, while in the analysis sex and gender are regarded as confounders. It is recommended that systems biologists systematically label the sex of the data and take this into account in the models they are building.

Naik et al. (2014) constructed the in silico model SteatoNet using liver metabolic data, to enhance understanding in research on liver disease etiology—but this model is valid for males only (Naik, Rozman, & Belic, 2014). Cvitanovic Tomas et al. (Cvitanovic Tomas, Urlep, Moskon, Mraz, & Rozman, 2018) have adapted SteatoNet to include sex differences by using data on estrogen and androgen receptor responses and consequent differences in growth hormone release. They call their computational model LiverSex and hope it will provide insight into sex-dependent liver pathologies. It has been validated for the mouse, but not yet for humans.

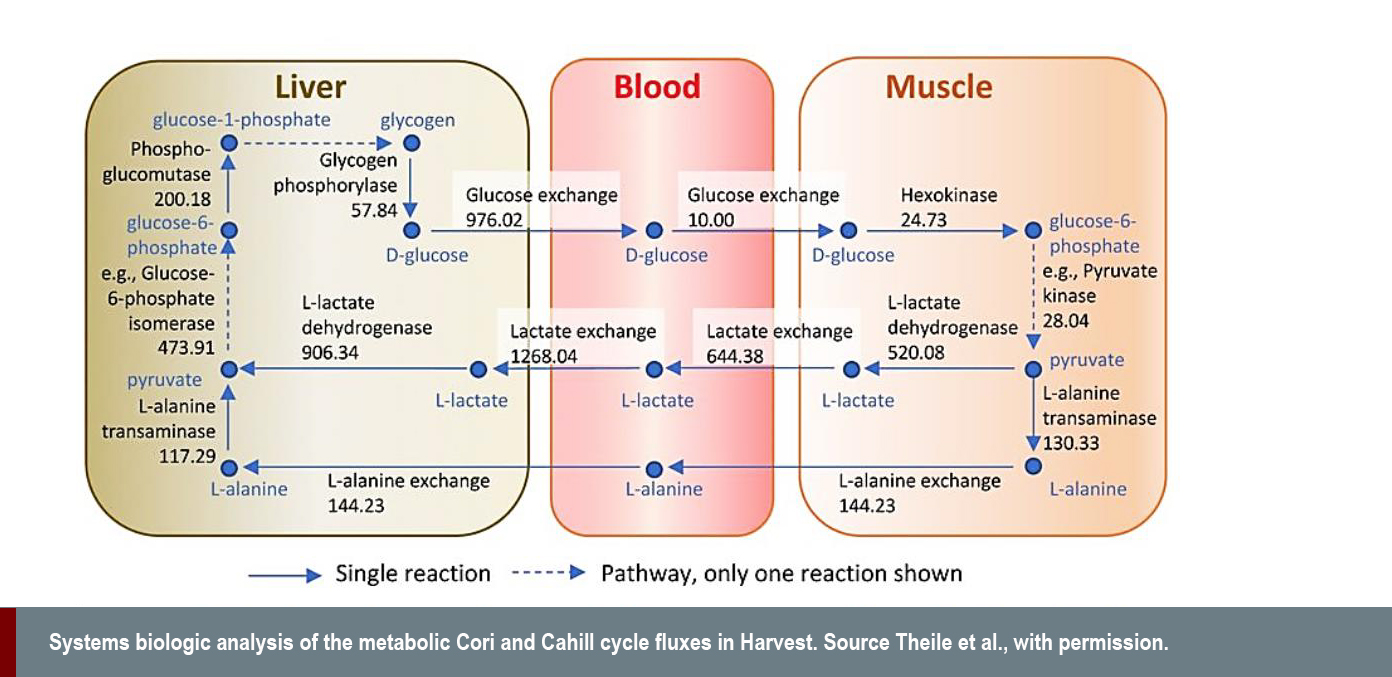

In the context of physiology and metabolism, researchers at the universities of Luxembourg and Leiden recently presented two validated, sex-specific, whole-body metabolic reconstructions, named Harvey and Harvetta (Thiele et al., 2018). The models represent the metabolism of twenty organs, six sex organs, six types of blood cells, the systemic blood circulation, the blood-brain barrier, and the gastrointestinal lumen with microbiome. There is potential for such models to be used to determine treatment methods in situations in which experimental testing is impossible, such as for pregnant women.

Conclusions

The human metabolism is influenced by sex and gender where genetic backgrounds interact with environmental factors that include lifestyle, ethnicity, culture, and social norms. Systems biology is a relatively new discipline with a growing impact in medical science. In the near future, it will enable the construction of mathematical models that can predict individual risk for common non-communicable diseases and guide best practices for prevention or therapy. Modeling is largely based on omics data, which at present lack information regarding sex and gender:

- 1. Studies on sexual dimorphism performed in humans under different living conditions are helpful for biological modeling.

- 2. Integrative omics will enable more individualized approaches to disease prevention and therapy. Source data need to include information on sex and gender (including cis- and non-binary genders).

- 3. The gut microbiome plays a role in health and risk for disease. Since the microbiome differs by sex, analysis of the microbiome should include sex as robust variable.

- 4. Although a few examples of male and female models of the human metabolism have been developed, the majority of models have been generated using male or mixed female/male data.

- 5. In such cases, the limitations of the model should be addressed. In some instances, the model can be retrofitted to include sex.

Next Steps

In systems biology the influence of sex and gender has received only limited attention. However, systems biology is still a young field. Now is the time to incorporate sex and gender as significant parameters in the design of omics experiments and mathematical modeling. Researchers, journals and funding agencies can raise awareness about the limits of single-sex datasets and make sex and gender analysis the norm in genomics, genetics and systems biology research.

Works Cited

Apweiler R. et al. (2018). Whither systems medicine? Experimental & Molecular Medicine, 50, e453.

Bielekova, B., Vodovotz, Y., An, G., & Hallenbeck, J. (2014). How implementation of systems biology into clinical trials accelerates understanding of diseases. Frontiers in neurology, 5.

Bielekova, B., Vodovotz, Y., An, G., & Hallenbeck, J. (2014). How implementation of systems biology into clinical trials accelerates understanding of diseases. Front Neurol, 5, 102. doi:10.3389/fneur.2014.00102

Cvitanovic Tomas, T., Urlep, Z., Moskon, M., Mraz, M., & Rozman, D. (2018). LiverSex Computational Model: Sexual Aspects in Hepatic Metabolism and Abnormalities. Front Physiol, 9, 360. doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.00360

Das A.V. et al. (2020). Clinical profile of pterygium in patients seeking eye care in India: electronic medical records-driven big data analytics report III. Int. Ophtalmol, 24 February.

Gemmati D. et al. (2020). "Bridging the Gap"everything that could have been avoided if we had applied gender medicine, pharmacogenetics and personalized medicine in the gender-omics and sex-omics era. Int J Mol Sci, 21, 296.

Karczewski, K. J., & Snyder, M. P. (2018). Integrative omics for health and disease. Nat Rev Genet, 19(5), 299-310. doi:10.1038/nrg.2018.4

Labonté B. et al. (2017). Sex-specific transcriptional signatures in human depression. Nat Med, 23 (9), 1102-1111.

Mittelstrass, K., Ried, J. S., Yu, Z., Krumsiek, J., Gieger, C., Prehn, C., . . . Illig, T. (2011). Discovery of sexual dimorphisms in metabolic and genetic biomarkers. PLoS Genet, 7(8), e1002215. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002215

Naik, A., Rozman, D., & Belic, A. (2014). SteatoNet: the first integrated human metabolic model with multi-layered regulation to investigate liver-associated pathologies. PLoS Comput Biol, 10(12), e1003993. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003993

Sinha, T., Vich Vila, A., Garmaeva, S., Jankipersadsing, S. A., Imhann, F., Collij, V., . . . Zhernakova, A. (2019). Analysis of 1135 gut metagenomes identifies sex-specific resistome profiles. Gut Microbes, 10(3), 358-366. doi:10.1080/19490976.2018.1528822

Tareen, S. H., Kutmon, M., Arts, I. C., de Kok, T. M., Evelo, C. T., & Adriaens, M. E. (2019). Logical modelling reveals the PDC-PDK interaction as the regulatory switch driving metabolic flexibility at the cellular level. Genes Nutr, 14, 27. doi:10.1186/s12263-019-0647-5

Tavassoly, I., Goldfarb, J., & Iyengar, R. (2018). Systems biology primer: the basic methods and approaches. Essays Biochem, 62(4), 487-500. doi:10.1042/ebc20180003

Thiele, I., Sahoo, S., Heinken, A., Heirendt, L., Aurich, M. K., Noronha, A., & Fleming, R. M. T. (2018). When metabolism meets physiology: Harvey and Harvetta. bioRxiv, 255885. doi:10.1101/255885

Thion, M. S., Low, D., Silvin, A., Chen, J., Grisel, P., Schulte-Schrepping, J., . . . Garel, S. (2018). Microbiome Influences Prenatal and Adult Microglia in a Sex-Specific Manner. Cell, 172(3), 500-516.e516. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.042

Wiik, A., Andersson, D. P., Brismar, T. B., Chanpen, S., Dhejne, C., Ekstrom, T. J., . . . Gustafsson, T. (2018). Metabolic and functional changes in transgender individuals following cross-sex hormone treatment: Design and methods of the GEnder Dysphoria Treatment in Sweden (GETS) study. Contemp Clin Trials Commun, 10, 148-153. doi:10.1016/j.conctc.2018.04.005

Zewde T.N. (2019) Multiscale solutions to quantitative systems biology models. Front Mol Biosci, 6, 119.

Systems biology is the integrative holistic understanding of biological systems. It is part of what is now referred to as systems medicine and aims to predict individual disease risk and precision treatment by mathematically modeling metabolic processes. Sex and gender roles can impact the human metabolism. Consequently, prevention and treatment of many non-communicable diseases require a sex- and gender-related approach.

Gendered Innovations:

1. Collecting data on sexual dimorphism in gene expression improves biological modeling. Accurate biological modeling can be assisted by studies of sexual dimorphism in human gene expression. Such studies should also take into account different ethnic, cultural, and societal backgrounds, and different lifestyles.

2. Collecting Sex and Gender Data Fuels Integrative Omics. Integrative omics provides a basis for sex-specific precision applications in various fields like medicine, pharmacotherapy, and nutrition. Current datasets underrepresent females and underreport participants’ gender identity.

3. Analyzing Sex Improves Understanding of the Role of the Microbiome in Health and Disease. Sex differences are found in the gut microbiome. Analyzing these differences will enhance our understanding of how the microbiome influences the human metabolism and will sharpen our efforts to improve human health.