Sex, Gender, & Intersectional Analysis

Case Studies

- Science

- Health & Medicine

- Chronic Pain

- Colorectal Cancer

- Covid-19

- De-Gendering the Knee

- Dietary Assessment Method

- Gendered-Related Variables

- Heart Disease in Diverse Populations

- Medical Technology

- Nanomedicine

- Nanotechnology-Based Screening for HPV

- Nutrigenomics

- Osteoporosis Research in Men

- Prescription Drugs

- Systems Biology

- Engineering

- Assistive Technologies for the Elderly

- Domestic Robots

- Extended Virtual Reality

- Facial Recognition

- Gendering Social Robots

- Haptic Technology

- HIV Microbicides

- Inclusive Crash Test Dummies

- Human Thorax Model

- Machine Learning

- Machine Translation

- Making Machines Talk

- Video Games

- Virtual Assistants and Chatbots

- Environment

Chronic Pain: Analyzing Sex, Gender, and Intersectionality

The Challenge

Sex, gender, and broader social factors, such as race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (SES), affect all parts of the pain pathway, from signaling to perception to expression and treatment. Recent studies have shown that women generally display a lower pain threshold across all types of pain—pressure, heat, cold, chemical or electrical stimulation, and ischemia (Bartley & Fillingim, 2013; Mogil, 2012). Some researchers attribute these differences solely to biological (sex) differences; others suggest that these observed differences are, at least in part, diminished or amplified by gender. The fact that women and men are raised to express pain differently may modify both their biological response to pain and their willingness to report it (Samulowitz et al., 2018). A better understanding of biological (sex) and sociocultural (gender) mechanisms of pain, and how these interact with pain management regimes, may lead to better health outcomes for pain patients. While women and men have historically dominated studies of gender in pain, research into pain among transgender and gender-diverse people is now underway.

More recent studies are adopting intersectional approaches. Newman and Thorn (2022) show that, in chronic pain, there was not a “universal gendered experience” but a dynamic interaction between gender and other social identities, such as age, sex, income, race/ethnicity, education, and literacy, associated with inequities. In their study, the most severely affected class was Black or African-American patients living below the poverty line with disabilities and low literacy.

Methods: Analyzing How Sex and Gender Interact

Biological mechanisms, such as sex hormones, influence the nervous and immune systems and thus the signaling, perception, expression, and response to treatment of pain. Gender roles and norms also influence pain. Gender norms, which vary across cultures, impact a patient’s perceived sensitivity to pain. During childhood, boys may be taught to be tough and stoic and girls to verbalize discomfort (Samulowitz et al., 2018). Researchers have demonstrated that these gender norms can be changed and that this can impact perceived sensitivity to pain (Robinson et al., 2003). Thus, observed biological differences (sexual dimorphism) might also be a consequence of gendered social and environmental influences.

Methods: Intersectional Approaches

An intersectional approach is important to consider when setting research priorities, developing hypotheses, and formulating research designs in studies involving human subjects. Taking an intersectional approach, for example, can better predict variations in health outcomes. The way the research problem is formulated will determine which intersecting variables are required for analysis. The most important categories, factors, and relationships cannot be determined a priori, but emerge during the process of investigation.Gendered Innovations:

1. Studying the Underlying Biological Mechanisms of Pain in Female-Typical Bodies and Male-Typical Bodies Promotes Sex-Specific Treatment: A better understanding of the influence of biological sex on the nervous and immune systems might help researchers design sex-tailored pain treatments.

2. Studying How Sex and Sex Interact: Men/boys, women/girls, and gender-diverse individuals are socialized to respond differently to pain and this might influence their sensitivity to pain. Researchers’ sex might also influence a research subject’s response to pain.

3. Studying How Sex/Gender, Race/Ethnicity, and Gender Diversity Intersect in Pain Reporting and Treatment: Sex and gender interact in chronic pain. These factors also intersect with other sociocultural factors, including age, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, education, and literacy. Physician sociocultural stereotypes and assumptions may also impact treatment regimes.

The Challenge

Gendered Innovation 1: Studying the Underlying Biological Mechanisms of Pain

Gendered Innovation 2: Studying How Sex and Sex Interact

Method: Intersectional Approaches

Gendered Innovation 3: How Gender Impacts the Reporting and Treatment of Pain

Conclusions

Next Steps

The Challenge

Sex and gender affect all parts of the pain pathway, from signaling to perception to expression and treatment. Recent studies have shown that women generally display a lower pain threshold across all types of pain—pressure, heat, cold, chemical or electrical stimulation, and ischemia (Bartley & Fillingim, 2013; Mogil, 2012). Some researchers attribute these differences solely to biological (sex) differences; others suggest that these observed differences are, at least in part, diminished or amplified by gender. The fact that women and men are raised to express pain differently may modify both their biological response to pain and their willingness to report it (Samulowitz et al., 2018). This case study focuses on how sex and gender interact in pain.

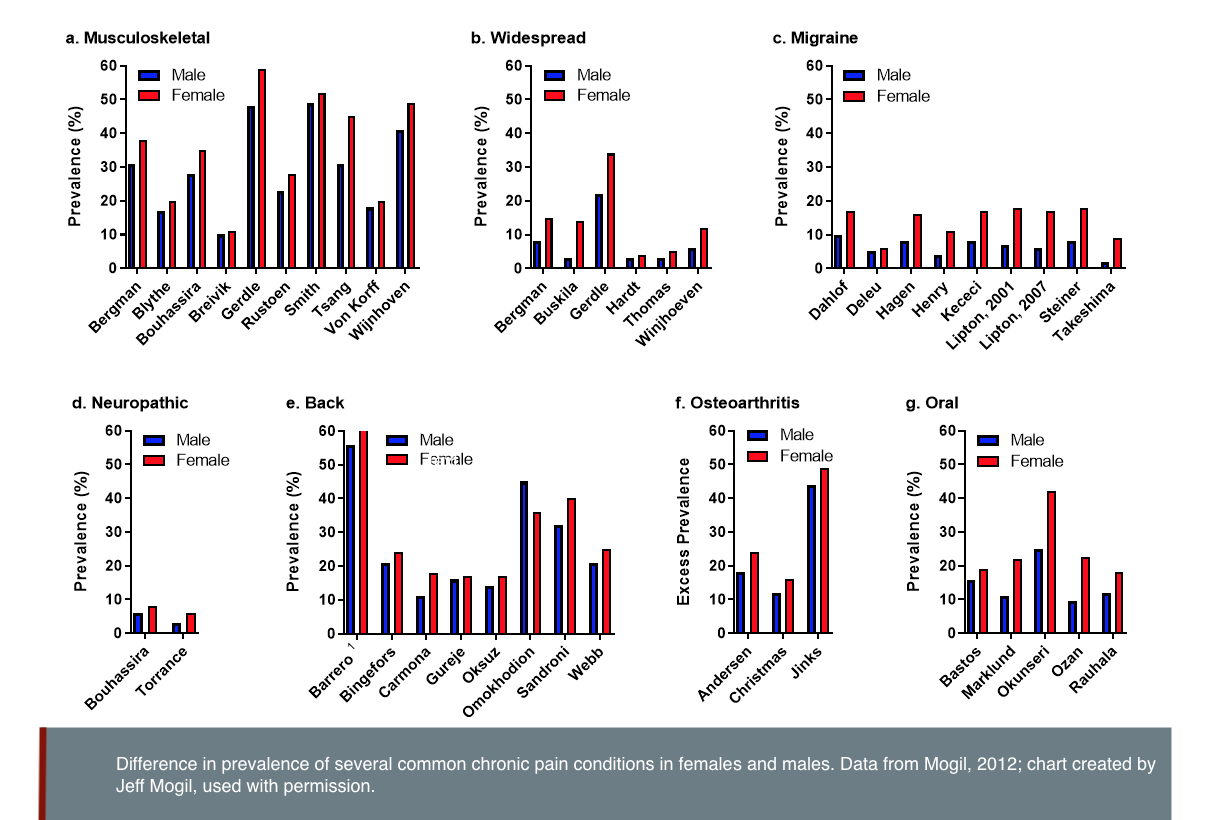

Chronic pain affects 20% of the adult population. Chronic pain refers to pain that persists past normal healing time and is commonly defined as pain that lasts more than 3 months (Merskey & Bogduk, 1994). Women, men and gender-diverse people all experience chronic pain. A higher prevalence of chronic pain has been reported in women compared to men (Greenspan et al., 2007; Mogil, 2012)—see figure below. Differences in the sources of pain also vary; migraine, rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia are more prevalent in women, while cluster headaches are more prevalent in men (Sorge & Totsch, 2017).

Gendered Innovation 1: Studying the Underlying Biological Mechanisms of Pain in Female-Typical Bodies and Male-Typical Bodies May Promote Sex-Specific Treatment

The nervous system and the immune system are both involved in the development, maintenance and control of chronic pain. In experiments with male and female mice, injuries to peripheral nerves caused an increased sensitivity to pain. In females, T lymphocytes (white blood cells) mediated the response. In males, the response depended on central nervous system cells called microglia (which act as immune cells) instead. The researchers found that testosterone activates microglia and suppresses T cells, while estrogens activate T cells. While in both cases the result is increased sensitivity to pain, the pathways are different. In the future this could possibly lead to the development of female and male-specific painkillers (Sorge & Totsch, 2017). The researchers could also show that changing hormonal profiles throughout the lifespan influenced the pain pathway. Pregnant female mice, for example, switched to the male-typical pathway, while male mice that lacked testosterone switched to the female-typical pathway. If the results can be confirmed in humans, this could impact humans throughout their lifetime, and affect treatment choices in patients undergoing hormone therapy.

Additional mechanisms might influence pain perception in females and males. Animal studies have shown that the number of certain pain receptors is higher in female brains (Sorge & Totsch, 2017), while the descending pain control pathways—where the brain inhibits pain perception despite injury—activate more strongly in males (Sorge & Totsch, 2017).

Similar sex differences may influence human pain. In the European Union-funded Horizon 2020 project, NGN-PET (NGN-PET), researchers are modelling neuron-glia networks in an effort to discover new pain treatments. The role of both neurons and glial cells in chronic pain is well-documented but has not been exploited to develop novel specific painkillers that target neuronal-glial interactions. One objective of this project is to understand the specific mechanisms involved in common neuropathic diseases and whether these explain the higher susceptibility of women to neuropathic pain. This approach might lead to a better understanding of sex-specific pain mechanisms, help identify new targets for pain treatments, and improve pain treatments in a sex-specific manner.

Gendered Innovation 2: Studying How Sex and Sex Interact

Researcher’s sex can also influence response to pain. In animal studies, mice and rats exposed to painful stimuli displayed less discomfort when the experimenter was male compared to a female (Sorge et al., 2014). The phenomenon appears to be mediated by olfactory stimuli, i.e. the animals smell the pheromones of the experimenter. Male rodents experienced physiological stress when smelling other males (in this case humans), which dampened the intensity of the perceived pain. This phenomenon, which the authors label the “male observer effect,” seemed to be present in both male and female rodents, though it was more pronounced in female rodents.

The role of olfactory substances in the modulation of pain has also been reported in humans (Villemure & Bushnell, 2007). In one study, olfactory exposure to androstadienone (a male sexual steroid) improved mood in women but not in men. When women were exposed to a pain stimulus, androstadienone increased pain intensity which might be explained by a heightened attentional state produced by the exposure to steroid hormones. Unfortunately, the researchers did not report the gender identity or sexual orientation of the participants, which might impact the female and male reactions to androstadienone.

Gendered Innovation 3: Studying How Sex/Gender, Race/Ethnicity, and Gender Diversity Intersect in Pain Reporting and Treatment

Sex and gender interact

Pain perception and expression are influenced by many factors, including social support, previous experience with pain, ethnicity, and the concomitant presence of other diseases like depression. Gender stereotypes can also modulate pain perception. In a study of 120 men in Germany, two groups of men were enrolled and given opposite preliminary information. One group was told that men were less sensitive to pain than women because of their evolutionary role as hunters, while the other group was told that women are less sensitive to pain because of the painful process of childbirth. The men in the first group reported less sensitivity to pain in the subsequent experiments. The associated imaging study (fMRI) suggests that this “gender priming” changed pain perception, not just the willingness to report pain (Schwarz et al., 2019). More research in this area, including with gender-diverse people, is needed (Abd-Elsayed et al., 2021).

Women’s higher risk of opioid dependency may be due not only to differences in metabolism (sex), but also to experiences of trauma or distress (gender) which are more prevalent in women. Some women—including women who have experienced violence, Aboriginal and Indigenous women (in Canada), non-cisgender women and trans women—have been found to be at a higher risk of opioid dependency (Hemsing et al., 2016).

Patient Gender

Gender roles and identity influence how pain is experienced, patients’ readiness to report pain, and pain management undertaken by healthcare professionals. Men may be less willing to report pain than women because dominant masculine gender roles associate male identity with toughness and stoicism (Robinson et al., 2001; Myers et al., 2003). Similarly, women are expected to report pain more readily. From childhood, girls and boys are frequently socialized to respond differently to pain; these attributes can vary across cultures and countries (Samulowitz et al., 2018). Researchers have demonstrated that these gender norms can be changed, which can in turn impact perceived sensitivity to pain (Robinson et al., 2003).

Patient race & ethnicity

Other sociocultural factors, including race and ethnicity, can also influence pain treatments. In U.S. emergency rooms, for example, white people are 25% more likely to receive medication for acute pain than Hispanic people and 40% more likely than African American people (Hoffman et al., 2016). Research is needed on chronic pain experience and treatment among other communities, particularly among Asian, Native American, and multiracial patients. One study found, for example, that Asian American patients showed the lowest pain prevalence across various pain definitions and model specifications. By contrast, Native American and multiracial patients showed the highest pain prevalence. It is important to understand that differences between ethnic groups often reflect socio-cultural inequities; for example, excess pain among Native Americans may be due to lower socioeconomic status (Zajacova et al., 2022; Kissi et al., 2022; Campbell & Edwards, 2012).

Patient sexual orientation; transgender and gender-diverse people

Research into pain among transgender and gender-diverse people (TGD) is just beginning. One study in Israel found that fibromyalgia (a chronic disorder that causes pain and tenderness throughout the body, as well as fatigue and trouble sleeping) is highly prevalent among Israeli transgender individuals, and that symptoms may be related to psychological distress and gender dysphoria (Pratt-Chapman et al., 2021). Transgender individuals are overall highly dissatisfied with their medical care (James et al., 2016).

Boerner (2023) points out that TGD people’s pain may include gender-related factors that can 1) be a source of risk (i.e., through minority stressors) or 2) promote strength and resiliency (through factors such as gender euphoria and a sense of belonging or community). Both pain and gender are embodied experiences, and pain may heighten the sense of disconnection between body and identity, as in the case of dysmenorrhea in trans masculine youth.

Intersectionality in pain

Newman and Thorn (2022) showed that, in chronic pain, there was not a “universal gendered experience” but a dynamic interaction between gender and other social identities (age, sex, income, race/ethnicity, education, and literacy) associated with inequities. The most severely affected class was Black or African-American patients with low socioeconomic status (SES), i.e., those below the poverty line, unemployed, with disabilities and low literacy or education). Another group characterized also by race (Black/African American) and low SES but who were older showed better outcomes, likely related to a better access to healthcare. The group characterized by female sex and employed showed the best outcomes.

A history of stressful life experiences, such as poverty or social discrimination, may also increase susceptibility to developing chronic forms of pain (Macgregor et al., 2023). In rodent pain models, animals exposed to repeated social/emotional forms of stress earlier in life exhibited greater hypersensitivity to both mechanical and thermal forms of pain later in life (Melchior et al., 2018). Pieritz et al. (2015) examined the relationship between a history of adverse life experiences and laboratory induced pain outcomes in a sample of healthy women and found that prior experiences of emotional abuse were associated with lower tolerance to heat pain at later points in time.

Method: Intersectional Approaches

An interactional approach is important to consider when setting research prioritew, developing hypotheses, and formulating research designs in studies involving human subjects. Taking an intersectional approach, for example, can better predict variations in health outcomes. While sex and gender are important concepts to consider (see Analyzing Sex; Analyzing Gender), they are shaped by other social and biological factors. The way the research problem is formulated will determine which intersecting variables are required for analysis. The most important categories, factors, and relationships cannot be determined a priori, but emerge during the process of investigation.

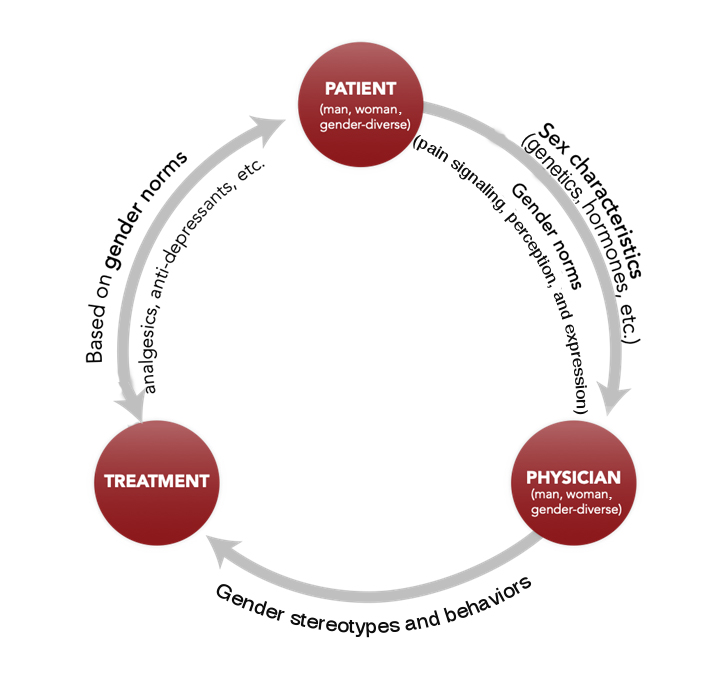

Healthcare providers, who themselves embody gender identity, norms, and relations, may treat their patients differently depending on their beliefs and subconscious assumptions. For example, in emergency medicine and prehospital settings, women with acute pain were prescribed fewer painkillers, especially opioids (Lord et al., 2009) and had to wait longer than men for treatment (Chen et al., 2008). In these acute settings, women appeared to receive more non-specific diagnoses, be treated less aggressively, and prescribed more antidepressants than painkillers compared to men (Hamberg et al., 2002; Hirsh et al., 2013; Hirsh et al., 2014). Conversely, women with chronic pain are more likely to be prescribed opioids than men (Serdarevic et al., 2017; Simoni-Wastila, 2000). This places women at higher risk of developing dependency and overdosing on prescribed opioids than men (Green et al. 2009; Unick et al. 2013). Nevertheless, deadly overdoses are higher in men than in women (Calcaterra et al., 2013).

The gender relations between provider and patient are complex. Researchers have found that women physicians were more likely to prescribe analgesics (painkillers) to patients in general and opioids to women patients, whereas men physicians were more likely to prescribe opioids to men patients (Safdar et al., 2009). In contrast, in an experimental study (as opposed to an observational one), Hirsh and colleagues found that women providers prescribed more antidepressants than men providers and offered more mental health referrals to women patients than to men patients (Hirsh et al., 2014). Women providers might be more inclined to consider psychosocial factors with women patients, which is in line with previous reports of the increased tendency of women physicians to discuss emotions and explore psychosocial factors (Roter, Hall, & Aoki, 2002). However, although emotional and psychological factors can contribute to chronic pain, women, men, and gender-diverse patients alike should have equal access to both medication and mental health treatment.

Physician gender also interacts with patient race/ethnicity. For renal colic, for example, men physicians tend to prescribe higher doses of painkillers (hydrocodone) to white vs. Black patients for renal colic, while women physicians prescribed higher doses to Black vs. white patients. Patient sex/gender may also play a role. When the patient is female, however, physicians overall prescribed lower doses to Black vs. white patients, whereas the reverse was true when the patient was male (Weisse et al., 2001; Weisse et al., 2003).

Conclusions

Both biological differences and sociocultural experiences across diverse populations influence chronic pain at all stages from signaling to treatment. A better understanding of how sex, gender, race, ethnicity, and TGD influence chronic pain may improve the quality of care provided to patients, the control of their pain, and their overall quality of life.

Much of the pain care in Europe and North America has been based on majority white, middle-class populations. Intersectional approaches that take into account divergent social identities, including age, class/socioeconomic status, disabilities, gender, migration status, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and transgender experiences, lead to more inclusive and equitable approaches to pain research and care (Macgregor et al. 2023; Walsh et al. 2022).

Next Steps

1. Preclinical and clinical studies must integrate new findings on sex differences in pain pathways to develop new treatments tailored to patient sex.

2. More research on the interaction between gender and the biology of pain is needed. These studies should include women, men, gender-diverse and transgender people from different sociocultural and ethnic backgrounds.

3. Future healthcare providers need to be taught the ways gender roles and behaviors across socioeconomic, cultural, and ethnic backgrounds impact pain management.

4. Adopting intersectional approaches can make pain research more inclusive (Janevic et al., 2022; Palermo et al., 2023).

Works Cited

Abd-Elsayed, A., Heyer, A. M., & Schatman, M. E. (2021). Disparities in the treatment of the LGBTQ population in chronic pain management. Journal of Pain Research, 3623-3625.

Bartley, E. J., & Fillingim, R. B. (2013). Sex differences in pain: a brief review of clinical and experimental findings. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 111(1), 52-58. doi:10.1093/bja/aet127

Bernardes, S. F., & Lima, M. L. (2010). Being less of a man or less of a woman: perceptions of chronic pain patients' gender identities. The European Journal of Pain, 14(2), 194-199. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.04.009

Boerner, K. E., Harrisonn, L. E., Battison, E. A. J., Murphy, C., Wilson, A. C. (2023) Topical Review: Acute and chronic pain experiences in transgender and gender-diverse youth. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 00, 1-8.

Burke, N. N., Finn, D. P., McGuire, B. E., & Roche, M. (2017) Psychological stress in early life as a predisposing factor for the development of chronic pain: Clinical and preclinical evidence and neurobiological mechanisms. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 95, 1257–1270.

Dance, A. (2019). The pain gap. Nature, 567, 448-450.

Calcaterra, S., Glanz, J., & Binswanger, I. A. (2013). National trends in pharmaceutical opioid related overdose deaths compared to other substance related overdose deaths: 1999-2009. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 131(3), 263-270. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.11.018

Campbell, C. M., & Edwards, R. R. (2012). Ethnic differences in pain and pain management. Pain Management, 2(3), 219–230.

Chen, E. H., Shofer, F. S., Dean, A. J., Hollander, J. E., Baxt, W. G., Robey, J. L., . . . Mills, A. M. (2008). Gender disparity in analgesic treatment of emergency department patients with acute abdominal pain. Academic Emergency Medicine, 15(5), 414-418. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00100.x

DOLORisk: understanding risk factors and determinants for neuropathic pain. Cordis. September 29, 2017. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/rcn/193238/factsheet/en.

Dragon, C. N., Guerino, P., Ewald, E., & Laffan, A. M. (2017). Transgender medicare beneficiaries and chronic conditions: exploring fee-for-service claims data. LGBT Health, 4(6), 404-411. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2016.0208

Fillingim, R. B., King, C. D., Ribeiro-Dasilva, M. C., Rahim-Williams, B., & Riley, J. L., 3rd. (2009). Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. The Journal of Pain, 10(5), 447-485. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.001

Green, T. C., Grimes Serrano, J. M., Licari, A., Budman, S. H., & Butler, S. F. (2009). Women who abuse prescription opioids: findings from the Addiction Severity Index-Multimedia Version Connect prescription opioid database. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 103(1-2), 65-73. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.03.014

Greenspan, J. D., Craft, R. M., LeResche, L., Arendt-Nielsen, L., Berkley, K. J., Fillingim, R. B., . . . Pain, S. I. G. o. t. I. (2007). Studying sex and gender differences in pain and analgesia: a consensus report. Pain, 132 Suppl. 1, S26-45. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2007.10.014

Hamberg, K., Risberg, G., Johansson, E. E., & Westman, G. (2002). Gender bias in physicians' management of neck pain: a study of the answers in a Swedish national examination. Journal of Women's Health & Gender-Based Medicine, 11(7), 653-666. doi:10.1089/152460902760360595

Hemsing, N., Greaves, L., Poole, N., & Schmidt, R. (2016). Misuse of prescription opioid medication among women: a scoping review. Pain Research and Management, 2016, 1754195. doi:10.1155/2016/1754195

Hirsh, A. T., Hollingshead, N. A., Bair, M. J., Matthias, M. S., Wu, J., & Kroenke, K. (2013). The influence of patient's sex, race and depression on clinician pain treatment decisions. The European Journal of Pain, 17(10), 1569-1579. doi:10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00355.x

Hirsh, A. T., Hollingshead, N. A., Matthias, M. S., Bair, M. J., & Kroenke, K. (2014). The influence of patient sex, provider sex, and sexist attitudes on pain treatment decisions. The Journal of Pain, 15(5), 551-559. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2014.02.003

Hoffmann, D. E., & Tarzian, A. J. (2001). The girl who cried pain: a bias against women in the treatment of pain. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 29(1), 13-27.

Hoffman, K. M., Trawalter, S., Axt, J. R., & Oliver, M. N. (2016). Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(16), 4296-4301.

James, S., Herman, J., Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., & Anafi, M. A. (2016). The report of the 2015 US transgender survey.

Janevic, M. R., Mathur, V. A., Booker, S. Q., Morais, C., Meints, S. M., Yeager, K. A., & Meghani, S. H. (2022). Making pain research more inclusive: Why and how. The Journal of Pain, 23, 707-728.

Kissi, A., Van Ryckeghem, D. M. L., Mende-Siedlecki, P., Hirsh, A., & Vervoort, T. (2022). Racial disparities in observers’ attention to and estimations of others’ pain. PAIN, 163(4), 745.

Lord, B., Cui, J., & Kelly, A. M. (2009). The impact of patient sex on paramedic pain management in the prehospital setting. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 27(5), 525-529. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2008.04.003

Macgregor C, Walumbe J, Tulle E, Seenan C, Blane DN. Intersectionality as a theoretical framework for researching health inequities in chronic pain. British Journal of Pain. 2023;17(5):479-90.

Melchior, M., Juif, P. E., Gazzo, G., Petit-Demoulière, N., Chavant, V., Lacaud, A., Goumon, Y., Charlet, A., Lelièvre, V., & Poisbeau, P. (2018) Pharmacological rescue of nociceptive hypersensitivity and oxytocin analgesia impairment in a rat model of neonatal maternal separation. Pain, 159, 2630–2640.

Merskey, H., & Bogduk, N. (1994). Classification of chronic pain. 2nd edition. Seattle: IASP Press.

Mogil, J. S. (2012). Sex differences in pain and pain inhibition: multiple explanations of a controversial phenomenon. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(12), 859-866. doi:10.1038/nrn3360

Myers, C. D., Riley, J. L., 3rd, & Robinson, M. E. (2003). Psychosocial contributions to sex-correlated differences in pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 19(4), 225-232.

Newman A. K., & Thorn B. E. Intersectional identity approach to chronic pain disparities using latent class analysis. Pain. 2022;163(4):e547-e56.

NGN-PET: Modeling Neuron-Glia Networks into a drug discovery platform for Pain Efficacious Treatments. Cordis. September 26, 2019. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/rcn/210123/factsheet/enPalermo, T. M., Davis, K. D., Bouhassira, D., Hurley, R. W., Katz, J. D., Keefe, F. J., ... & Yarnitsky, D. (2023). Promoting inclusion, diversity, and equity in pain science. Pain Medicine, 24(2), 105-109.

Pieritz, K., Rief, W., & Euteneuer, F. (2015). Childhood adversities and laboratory pain perception. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 11, 2109–2116.

Pratt-Chapman, M. L., Murphy, J., Hines, D., Brazinskaite, R., Warren, A. R., & Radix, A. (2021). “When the pain is so acute or if I think that I’m going to die”: Health care seeking behaviors and experiences of transgender and gender diverse people in an urban area. Plos one, 16(2), e0246883.

Robinson, M. E., Gagnon, C. M., Riley, J. L., 3rd, & Price, D. D. (2003). Altering gender role expectations: effects on pain tolerance, pain threshold, and pain ratings. The Journal of Pain, 4(5), 284-288.

Robinson, M. E., Riley, J. L., 3rd, Myers, C. D., Papas, R. K., Wise, E. A., Waxenberg, L. B., & Fillingim, R. B. (2001). Gender role expectations of pain: relationship to sex differences in pain. The Journal of Pain, 2(5), 251-257. doi:10.1054/jpai.2001.24551

Roter, D. L., Hall, J. A., & Aoki, Y. (2002). Physician gender effects in medical communication: a meta-analytic review. JAMA, 288(6), 756-764. doi:10.1001/jama.288.6.756

Safdar, B., Heins, A., Homel, P., Miner, J., Neighbor, M., DeSandre, P., . . . Emergency Medicine Initiative Study, G. (2009). Impact of physician and patient gender on pain management in the emergency department--a multicenter study. Pain Medicine, 10(2), 364-372. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00524.x

Samulowitz, A., Gremyr, I., Eriksson, E., & Hensing, G. (2018). “Brave men” and “emotional women”: a theory-guided literature review on gender bias in health care and gendered norms towards patients with chronic pain. Pain Research and Management, 2018. doi:10.1155/2018/6358624

Schwarz, K. A., Sprenger, C., Hidalgo, P., Pfister, R., Diekhof, E. K., & Buchel, C. (2019). How stereotypes affect pain. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 8626. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-45044-y

Serdarevic, M., Striley, C. W., & Cottler, L. B. (2017). Sex differences in prescription opioid use. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 30(4), 238-246. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000337

Simoni-Wastila, L. (2000). The use of abusable prescription drugs: the role of gender. Journal of Women's Health & Gender-Based Medicine, 9(3), 289-297. doi:10.1089/152460900318470

Sorge, R. E., Mapplebeck, J. C., Rosen, S., Beggs, S., Taves, S., Alexander, J. K., . . . Mogil, J. S. (2015). Different immune cells mediate mechanical pain hypersensitivity in male and female mice. Nature Neuroscience, 18(8), 1081-1083. doi:10.1038/nn.4053

Sorge, R. E., Martin, L. J., Isbester, K. A., Sotocinal, S. G., Rosen, S., Tuttle, A. H., . . . Mogil, J. S. (2014). Olfactory exposure to males, including men, causes stress and related analgesia in rodents. Nature Methods, 11(6), 629-632. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2935

Sorge, R. E., & Totsch, S. K. (2017). Sex Differences in Pain. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 95(6), 1271-1281. doi:10.1002/jnr.23841

Unick, G. J., Rosenblum, D., Mars, S., & Ciccarone, D. (2013). Intertwined epidemics: national demographic trends in hospitalizations for heroin- and opioid-related overdoses, 1993-2009. PLoS One, 8(2), e54496. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054496

Villemure, C., & Bushnell, M. C. (2007). The effects of the steroid androstadienone and pleasant odorants on the mood and pain perception of men and women. European Journal of Pain, 11(2), 181-191. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.02.005

Walsh D. et al. (2022) Bearing the burden of austerity: how do changing mortality rates in the UK compare between men and women? J Epidemiol Community Health, vol.76: 1027–1033.

Weisse C. S., Sorum P. C., Sanders K. N, & Syat B. L. Do gender and race affect decisions about pain management? J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(4):211-7.

Weisse C. S., Sorum P. C., & Dominguez R. E. The influence of gender and race on physicians' pain management decisions. J Pain. 2003;4(9):505-10.

Zajacova, A., Grol-Prokopczyk, H., & Fillingim, R. (2022). Beyond Black vs White: Racial/ethnic disparities in chronic pain including Hispanic, Asian, Native American, and multiracial US adults. PAIN, 163(9), 1688.

Women, men, and gender-diverse individuals perceive pain differently. They often express pain differently and may receive different treatments. A better understanding of sex and gender differences in pain may lead to better health outcomes.

Gendered innovations:

1. Studying the Underlying Biological Mechanisms of Pain in Women and Men Promotes Sex-Specific Treatment. A better understanding of the influence of biological sex on the nervous and immune systems might help researchers design sex-tailored pain treatments.

2. Studying How Sex and Gender Interact. Men/boys, women/girls, and gender-diverse individuals are socialized to respond differently to pain, and this might influence their sensitivity to pain. Men, for example, may be less willing to report pain than women because gender roles in Western cultures often associate male identity with toughness and stoicism.

3. Understanding How Gender Impacts the Reporting and Treatment of Pain. Gender stereotypes can influence how pain is experienced, a patient’s willingness to report pain, and how healthcare professionals manage pain. For example, some healthcare providers are more likely to classify pain as psychological in women compared to men.