Sex, Gender, & Intersectional Analysis

Case Studies

- Science

- Health & Medicine

- Chronic Pain

- Colorectal Cancer

- Covid-19

- De-Gendering the Knee

- Dietary Assessment Method

- Gendered-Related Variables

- Heart Disease in Diverse Populations

- Medical Technology

- Nanomedicine

- Nanotechnology-Based Screening for HPV

- Nutrigenomics

- Osteoporosis Research in Men

- Prescription Drugs

- Systems Biology

- Engineering

- Assistive Technologies for the Elderly

- Domestic Robots

- Extended Virtual Reality

- Facial Recognition

- Gendering Social Robots

- Haptic Technology

- HIV Microbicides

- Inclusive Crash Test Dummies

- Human Thorax Model

- Machine Learning

- Machine Translation

- Making Machines Talk

- Video Games

- Virtual Assistants and Chatbots

- Environment

Quality Urban Spaces: Gender Impact Assessment

The Challenge

The quality of urban spaces in everyday life is important for many, particularly children, caregivers, and elderly people. These groups spend more time in public spaces compared to working age women and men, and may face specific risks in public spaces (Sánchez de Madariaga & Neuman, 2020). Planning and designing public spaces that respond to the specific everyday needs of young children, caregivers, and the elderly make cities work for all. This case study will look at innovations and methods used in various cities to improve the quality of urban spaces in both suburban and dense urban environments, in the developed and the developing worlds.

Method: Gender Impact Assessments

Gender impact assessments allow city planners to understand who benefits from urban design and who is left out. From the results, conclusions can be drawn about what could be relevant for broader applications. Gender impact assessments produce systematic evaluations for developing more general recommendations. Where relevant, these assessments should include intersectional variables

Gendered Innovations:

1. Building Child-Friendly and Family-Friendly Streets and Public Spaces

Streets and urban public spaces are often designed and built giving priority to the needs of cars over the needs of people. Quality streets and public spaces require responding to the daily needs of people, particularly of children, the elderly, and their caregivers.

2. Building Playgrounds for Children of Different Ages and Genders

Children of different ages and genders use spaces in different ways, which sometimes conflict with one another. Considering the specificities of age and gender will improve the quality of playgrounds for all children.

Gendered Innovation 1: Building Child-Friendly and Family-Friendly Streets and Public Spaces

Gendered Innovation 2:Building Playgrounds for Girls and Boys of Different Ages

Method: Gender Impact Assessments

Method: Planning and Design Guidelines and Manuals

Conclusions

Next Steps

The Challenge

The physical features of urban space are key elements for supporting everyday life for all citizens independent of gender, age, socioeconomic status, race, physical ability, ethnicity, or other personal circumstances. When urban spaces are unsafe or inadequate, everybody suffers. Issues include narrow, poorly maintained or non-existent pavements; scarce or remote healthcare, educational, cultural or sports facilities, shops and workplaces; scarce or unsafe playgrounds and green areas. The lives of some people, including children, the elderly, and caregivers, can become especially difficult and limited (UNICEF, 2018; Bernard Van Leer Foundation, 2018).

While men are increasingly taking a larger share of caring responsibilities (O'Brien et al., 2003), women still do more. In 10 EU countries, in households with parents living as a different-sex couple with small children, women perform an average of 2 hours and 21 minutes of childcare per day compared to men’s 59 minutes (European Communities, 2004). This pattern holds in the U.S. as well. In 2018, the average U.S. mother spent 1 hour and 49 minutes caring for and helping children in her household, more than twice the average U.S. father’s 52 minutes (United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019). Single-parent households constitute a growing percentage of all households, and the parent is typically a woman. These households face additional difficulties in combining paid employment with caring duties and are among those in most need of support.

Where urban design is inadequate, children will not have the chance to grow up safely while exploring new boundaries and gaining autonomy. The elderly will not be able to lead an active autonomous life. Mothers and other caregivers will struggle to balance paid employment with their care responsibilities. Lower-income people, as well as racial and ethnic minorities, who are often concentrated in lower-income areas, will live in neighborhoods with comparatively poor urban spaces because of patterns of spatial segregation in cities around the world. As a result, women, children and the elderly from these groups will endure comparatively greater life limitations because of poor-quality urban spaces. While transgender and gender-diverse individuals suffer bullying and violence in public spaces (Eisenberg et al., 2019), the extent to which this can be addressed through urban design is limited.

Quality urban spaces designed to respond to the specific everyday life needs of women, children and the elderly is not, however, the norm. Suburban areas typical of North American cities lack sufficient density to ensure that facilities used on a daily basis, such as schools, doctors or sports fields, are within walking distance, which would allow young people to access them unaccompanied. Additionally, often there are insufficient passers-by in these areas to provide the informal supervision that affords a sense of safety.

At the same time, cities in which high-density development and residential neighborhoods are the norm often lack open green areas and playgrounds that can be used safely by unaccompanied young people. In suburban areas, such outdoor spaces are on private property, as part of patios or gardens in residential developments. In high-density neighborhoods, green space is often missing, and children lack opportunities for play and exercise. Both children and adults often lack opportunities for social interaction and a sense of community.

In the developing world, all these problems coalesce and are often more severe, with a lack of walkable streets, public spaces, playgrounds, easily accessible facilities and amenities, and basic urban infrastructure such as pavements or even lighting (INIUA, 2017).

Improving the quality of urban spaces by looking at the specific needs of children, the elderly and caregivers will create better urban environments for everyone. Improving the quality of urban spaces in ways that provide better support for these groups is a challenge that will require design solutions and measures tailored to both low-density and high-density environments, taking into account the economic capacities and constraints of cities and countries.

The main physical characteristics of streets and public spaces that support the daily lives of children and their families include (Gehl Institute, 2018; NACTO, 2018; ODI, 2017; Krishnamurti et al., 2018; Sánchez de Madariaga & Neuman, 2020):

- 1. walkable streets with reduced traffic that enable and encourage active independent mobility for young people, the elderly and everyone else, and reduce the adverse health effects of pollution (particularly severe for children, because they breath at the height of exhaust pipes and their bodies are still maturing)

- 2. formal and informal natural public spaces for outdoor play that encourage the physical, psychological, emotional and mental development of children and support their caregivers

- 3. formal and informal indoor and outdoor community spaces that create opportunities for social connectedness, promote a sense of ownership, and support the development of agency and the decision-making capabilities of young people

- 4. sufficiently dense and mixed-use spaces which facilitate undertaking daily activities within walking distance from home, including independent school attendance, shopping for groceries, seeing a doctor, and sport.

Gendered Innovation 1: Building Child-Friendly and Family-Friendly Streets and Public Spaces

Numerous initiatives around the world have improved public spaces for children and their families.

Japan provides a striking example of how cities can develop child-friendly routes to school. Unlike in most countries today, Japanese children are expected to go to school on their own from a very young age, either using public transport or on foot. Both schools and local governments work together to plan, design and build physical features of sidewalks and streets along children’s school routes. Physical improvements can include one or several of the following (Krysiak, 2019): relocating pedestrian crossings; longer green lights for pedestrians; temporary traffic closures near schools at peak times; signs to alert drivers that there are schoolchildren nearby; pictograms such as small feet painted at crossings to remind children to watch out for traffic.

The Bernard Van Leer Foundation, a Dutch organization, works with cities around the world to improve urban space and streets for toddlers and children through its Urban95 program (Bernard Van Leer, 2018). In Lima, for instance, the Urban95 program has developed child-friendly routes to preschool bringing together three local governments—the municipalities of Carabayllo, Comas, and San Juan de Miraflores—with non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The project addressed the travel needs of toddlers and parents living in the hilly neighborhood of Alto Perú who chose to take long and expensive taxi trips because the shortest pedestrian route was dangerously steep, garbage-ridden and uneven. The project involved cleaning up trash, building retaining walls, installing double handrails at adult and toddler heights, planting trees and vegetation, and adding seating and rest areas.

The City of Vienna developed a specific pilot project to improve public space in Mariahilf (Irschik & Kail, 2013), a small and dense central district with narrow streets and some vertical inclines of up to 31 meters. Before the intervention, Mariahilf had about fifty public stairways and flights of steps, more than thirty of which were without ramps; about 25 percent of all sidewalks were less than two meters wide, below the minimum width needed for walking in pairs; about 50 percent of all intersections were difficult for pedestrians to cross. The project sought to reduce these architectural barriers and improve safety. This involved developing a checklist for street design to address both technical standards for pedestrian movement and social factors such as pedestrian routes to major destinations in the district. As a result, planners: widened more than 1000 meters of pavement; improved more than sixty intersections that reduced pedestrian crossing times; implemented barrier-free design across the neighborhood; installed numerous seating facilities; installed new lighting in twenty-six spots; and refurbished three public squares.

In the U.S., the non-profit organization KaBOOM! works to support child development in low income areas by creating opportunities for play in public space for children in collaboration with cities around the country. In collaboration with the William Penn Foundation of Philadelphia, KaBOOM! developed Play Everywhere Philly (Play Everywhere, 2018). This is a city-wide competition awarding a million U.S. dollars in grants for local groups working with professional designers to create interactive play installations. The interventions involve the creation of play-oriented learning features on pavements and footpaths, at bus stops, and outside business premises for children aged 0–8. These included objects, sculptures, drawings, plantings, signs, symbols, words, texts, or games aimed at stimulating children’s attention, involvement and imagination.

Pioneering work on women’s safety was developed and carried out by Montréal and Toronto in the 1990s (Michaud, 1997). Numerous cities around the world are now implementing the methodology developed in Canada. This methodology called “exploratory safety audits” includes walking with women to determine the following safety principles (UN Women, 2011):

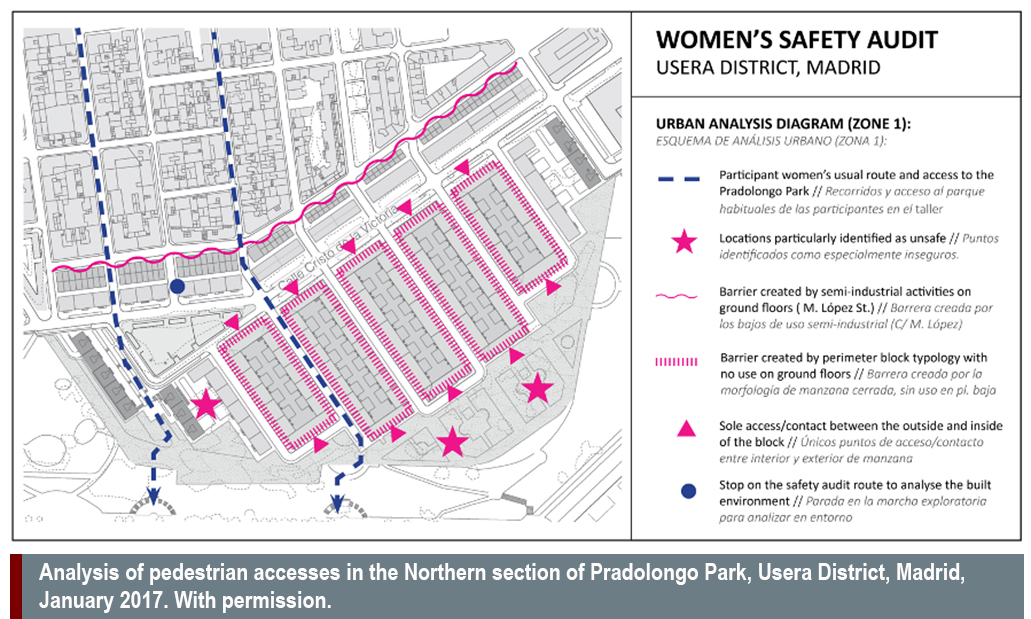

Exploratory safety walks with women allow city planners identify dangerous neighborhoods or transportation segments (Sánchez de Madariaga, 2004). A study in the area surrounding the Pradolongo Park in the Usera District of Madrid applied this methodology through the following steps (Novella & Izquierdo, 2017): an initial workshop in which neighborhood women worked with professional planners; the exploratory walk itself; the drafting of the report; a final workshop with the local women. The results were mapped and specific recommendations made to the city on where and how to improve urban design.

Gendered Innovation 2: Building Playgrounds for Girls and Boys of Different Ages

Playgrounds in residential complexes or in public spaces can be specifically designed for girls and boys of different ages as well as for the elderly. The city of Vienna redesigned several parks after a study in the mid-1990s found that the presence of girls in parks and public playgrounds decreases significantly from the age of 10, with consequences for their self-confidence and body awareness (Irschik & Kail, 2013). The internationally recognized housing complex Frauenwerkstadt, designed by Franziska Ullmann for the City of Vienna includes a variety of open spaces specifically designed for the playing and social needs of boys and girls of different ages.The program “Gender-Sensitive Parks, Sports Grounds, and Playgrounds for Children and Young People in Vienna’s Municipal Districts,” involved two pilot projects and the redesign of four additional parks around the city. The objective was to explore spatial configurations that would support girls’ and women’s use of public space and sense of belonging. Participatory workshops with neighborhood girls revealed girls’ priorities park redesign: a facility for girls only, an area for play and sports not dominated by boys, a “communication zone” for socializing and meeting new people, a clear sub-division of the space into different areas offering higher and lower levels of activity and privacy. Similar participatory workshops could be carried out with young LGBTQ+ people.

Vienna authorities then carried out a gender assessment to understand which projects could be scaled up. The evaluation consisted of a landscape analysis of fourteen parks and a detailed user and spatial pattern analysis of five parks, including the two earlier pilot projects. This analysis resulted in a series of working group meetings that included representatives of the departments involved, representatives from youth services, and the landscape architects for the model projects. The objective of the meetings was to develop “Planning Recommendations for the Gender-Sensitive Design of Public Parks” for the city (Damyanovic et al., 2014, 82-84). The most important aspects of the recommendations include safety and visibility, as well as the provision of quiet areas and areas designed for activities preferred by girls, such as skating, volleyball and badminton. In parks with heavy use, the recommendation is to divide the larger spaces and ball-game areas into smaller sub-areas to prevent larger areas from being occupied exclusively by the most dominant group.

Since 2007, these recommendations, along with the general “Park Design Guidelines”, must be taken into account by all contractors for the City of Vienna’s Department of Parks and Gardens. Girls and boys in different cities may have different preferences, but cities can use similar processes to design inclusive parks.

Method: Gender Impact Assessments

The experience acquired through pilot projects needs to be evaluated through gender assessments of impacts in order to understand who benefits from urban design and who is left out. From the results, conclusions can be drawn as to what could be relevant for broader applications. Gender impact assessments produce systematic evaluations for developing more general recommendations. Where relevant, these assessments should include intersectional variables.

Method: Planning and Design Guidelines and Manuals

Manuals and guidelines are important policy tools used for gender mainstreaming or when the implementation of a new policy requires the acquisition of new skills and/or institutional capacity building. They provide systematic recommendations, examples of good practice, illustrations, references and checklists for professionals and officials in charge of implementation (Zibell et al., 2019).

Conclusions

Since World War II, cities have been designed primarily for cars, with little thought given to pedestrians. This has disproportionately impacted children and the elderly, the most vulnerable groups of pedestrians, limiting their free mobility in public spaces. Most cities around the world today do not provide minimum standards for quality public spaces for many of their youngest residents. Quality safe streets and public spaces in which children can play, explore, socialise and travel autonomously are critical for their physical, psychological, and mental development. Such spaces also benefit caregivers, the elderly and gender-diverse people. Quality public spaces for young people also require consideration of gender differences in the use of public spaces at different ages. Individual projects at different urban scales and locations in cities around the world are showing how to create liveable streets and open spaces in which children can play safely, but they are still by no means the norm. Cities like Amsterdam, which has a wide network of playgrounds of different sizes and shapes within a relatively dense residential development, provide a glimpse into possible futures.

Next Steps

Good practices, as highlighted in this case study, can provide a foundation for broader policy developments. Good practice emerges from specific local cultures and urban structures, including density and urban morphology, the funding and administrative capabilities of cities, planning systems, design cultures, etc.Future Basic Research

-

1. Research on the interaction of children—girls and boys—the elderly, women, men and gender non-conforming people with their specific urban environments. Research must be specific to local culture, local urban morphologies, and local planning cultures and systems.

2. Research on policy processes needed to create wider support for more systematic change.

Policy

1. Disseminate existing research and good practice.

2. Create context-specific guidelines and manuals.

3. Develop norms and regulations that support livable streets and public parks and playgrounds for everyone.

4. Create institutional capacity for effective implementation.

5. Promote alliances of different stakeholders to support coordinated policies addressing the needs of children and other vulnerable populations in the city.

Works Cited

Bernard van Leer Foundation (2018), Urban95 Starter Kit (https://bernardvanleer.org/app/uploads/2018/05/Urban95-Starter-Kit-2.pdf).

Damyanovic, D., Reinwald, F. & Weikmann, A. (2013). Gender mainstreaming in urban planning and urban development. Vienna: Urban Development Vienna, Municipal Department 18 (MA 18) – Urban Development and Planning. Available at: www.wien.gv.at/stadtentwicklung/studien/pdf/b008358.pdf.

European Communities. (2004). How Europeans Spend their Time: Everyday Life of Women and Men. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3930297/5953614/KS-58-04-998-EN.PDF/c789a2ce-ed5b-4a0c-bcbf-693e699db7d7?version=1.0

Eisenberg, M. E., Gower, A. L., McMorris, B. J., Rider, G. N., & Coleman, E. (2019). Emotional distress, bullying victimization, and protective factors among transgender and gender diverse adolescents in city, suburban, town, and rural locations. The Journal of Rural Health, 35(2), 270-281.

Gehl Institute (2018). Space To Grow: Ten Principles that Support Happy, Healthy Families in a Playful, Friendly City. https://gehlinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/GehlInstitute_SpaceToGrow_single_pages.pdf

India’s National Institute of Urban Affairs (INIUA) (2017). Compendium of Best Practices of Child Friendly Cities. https://cfsc.niua.org/sites/default/files/Compendium_of_Best_Practices_of_Child

_Friendly_Cities_2017.pdf

Irschik, E., & Kail, E. (2013). Vienna: Progress Towards a Fair Shared City. In I. Sánchez de Madariaga & M. Roberts (Eds.). Fair Shared Cities. The Impact of Gender Planning in Europe. New York: Ashgate, pp. 193-230.

KaBOOM! (2018), Play Everywhere Playbook (https://kaboom.org/playbook).

Krishnamurthy, S., Steenhuis, C., & Reijnders, D. A. H. (2018). Mix & Match: Tools to Design Urban Play. Eindhoven: Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. https://research.tue.nl/en/publications/mix-amp-match-tools-to-design-urban-play

Krysiak, N. (2019). Designing Child-Friendly High Density Neighborhoods: Transforming Our Cities for the Health, Wellbeing and Happiness of Children, Churchill Trust. www.citiesforplay.com

Michaud, A. et al. (1997) Une ville à la mesure des femmes, le rôle des municipalités dans l'atteinte de l'objectif d'égalité entre hommes et femmes. Montreal: Ville de Montreal.

National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) (2015). Global Street Design Guide. https://nacto.org/global-street-design-guide-gsdg/

Novella Abril, I., Izquierdo García, L. (2017). Marchas Exploratorias Piloto en el Distrito de Usera. Informe de resultados y recomendaciones básicas. Cátedra UNESCO de Género, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid https://www.gendersteunescochair.com/project/exploratorywalks/

O'Brien, M. & Shemilt, I. (2003). Working Fathers: Earning and Caring. Manchester: Equal Opportunities Commission.

Open Data Institute (ODI) (2017). How Dashboards Can Help Cities Improve Early Childhood Development. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED582025

Sánchez de Madariaga, I. & M.Neuman (2020) “Planning the Gendered City” in Sánchez de Madariaga, Inés and M. Neuman, (eds.) Engendering Cities: Designing Sustainable Urban Spaces for All, Routledge, New York.

Sánchez de Madariaga, I. (2004). Urbanismo con perspectiva de género, Sevilla: Fondo Social Europeo – Junta de Andalucía.

UNICEF (2018). Handbook on Child-Responsive Urban Planning. https://www.unicef.org/publications/index_103349.html

UN Women, Building Safe and Inclusive Cities for Women: A Practical Guide (New Delhi, 2011). http://www.stopstreetharassment.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/5-13-add-building-safe-inclusive-cities-for-women.pdf

United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2019). News Release: American Time Use Survey – 2018 Results.

Zibell, B., Damyanovic, D., & Strum, U. (Eds.) (2019). Gendered approaches to spatial development in Europe. Routledge, Oxon, New York.