Sex, Gender, & Intersectional Analysis

Case Studies

- Science

- Health & Medicine

- Chronic Pain

- Colorectal Cancer

- Covid-19

- De-Gendering the Knee

- Dietary Assessment Method

- Gendered-Related Variables

- Heart Disease in Diverse Populations

- Medical Technology

- Nanomedicine

- Nanotechnology-Based Screening for HPV

- Nutrigenomics

- Osteoporosis Research in Men

- Prescription Drugs

- Systems Biology

- Engineering

- Assistive Technologies for the Elderly

- Domestic Robots

- Extended Virtual Reality

- Facial Recognition

- Gendering Social Robots

- Haptic Technology

- HIV Microbicides

- Inclusive Crash Test Dummies

- Human Thorax Model

- Machine Learning

- Machine Translation

- Making Machines Talk

- Video Games

- Virtual Assistants and Chatbots

- Environment

Video Games: Engineering Innovation Processes

The Challenge

Video games are one of the largest media outlets in the 21st century, with revenue in the US games market exceeding $43 billion in 2018. Video games serve as an important source of information, social interaction, entertainment, and exploration of personal identity. Many game characters typify various gender, racial, and queer stereotypes. Negative stereotypes are a cause for concern because games immerse players in interactive and compelling stories that can shape social values and norms as well as individual behaviors.

Method: Rethinking Language and Visual Representations

Games provide a virtual space where both designers and players can experiment with identities, including ethnic, gender, and sexual identities. This experimentation can manifest in ways that might be difficult or impossible in the real world. Challenging stereotypes, not just reversing them, has the potential to help remake real-world identities and behaviors, and may enhance diversity among players and game developers.

Gendered Innovations:

- Games may serve as catalysts for social change. Challenging social norms and stereotypes may enhance diversity in video and online games, and potentially within the gaming industry itself. This is important because games are spaces where people of all ages socialize.

- Developers can create diverse characters and avatars. Providing diverse characters and avatar options in games can drive inclusivity. Games are increasingly featuring more female characters, as well as LGBTQIA+ and BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) characters that are beginning to receive narrative parity with their majority white male counterparts.

The Challenge

Gendered Innovation 1: Games as a Catalyst for Changing Gender Norms

Method: Rethinking Language and Visual Representations

Designing Games for Girls: The Problem of Stereotypes

Term: Stereotypes

Gendered Innovation 2: Designing Flexible, Mixed-Gender Games

Method: Engineering Innovation Processes

Video Games and Women’s Participation in the Information Technology (IT) Industry

Conclusions

Next Steps

The Challenge

In 1962, MIT student Steve Russell created Spacewar!, the first widely-distributed software video game (Rockwell, 2002). Until games were commercialized in 1971, developers and players were largely computer scientists, electrical engineers, and their students, who tended to be white males (Herman et al., 2002). Fifty years later, we still lack equity among game characters, gamers, and developers.

Gendered Innovation 1: Games as a Catalyst for Changing Social Norms

Video games are one of the largest media outlets in the 21st century, serving as a source of information, social interaction, entertainment, and exploration of personal identity (Westcott et al., 2021).

Games—and the cultures that form around them—often reflect and influence players’ behaviors in the real world. For example, controlled experiments show that violent game play, such as Mortal Kombat, increases the incidence of self-reported aggressive thoughts in the short term (Anderson et al., 2007). Similarly, research demonstrates that players exposed to stereotypical sex-typed images from video games (e.g., female sex objects and powerful males) are more tolerant of sexual harassment (Dill et al., 2008). Researchers also found that players exposed to stereotypes of Black men as aggressive criminals or a “dangerous minority” rate Black political candidates less favorably than white candidates (Dill & Burgess, 2013). Finally, games that are consistently heteronormative erase LGBTQIA+ identities. By contrast, games where the goal is “to benefit another game character” have been shown to enhance gamers’ prosocial action, or voluntary actions intended to help others (Greitemeyer et al., 2010).

This power of games to influence social behavior can potentially help catalyze social change (Stefansdóttir et al., 2008). Game researchers have found that games embed “beliefs within their representation systems and structures, whether the designers intend them or not” (Flanagan et al., 2007). In this sense, games can either reproduce social stereotypes or challenge them—in ways that lead players to rethink social norms (see diagram right). Analyzing gender, race, sexuality, and their intersections has led to the designing of games which provide a virtual space where players can explore social identities and behaviors. Games that challenge conventional stereotypes allow players to create multiple personas in a range of contexts over time.

Gendered Innovation 2: Designing Diverse Characters and Avatars

Gender, racial, and queer stereotypes are rife in games. Stereotypes have both cognitive (e.g., generalizations) and affective (e.g., fear) components (Amodio & Devine, 2006), and repeated exposure to stereotypical portrayals of a group reinforces how that group is viewed socially (Burgess, 2011).

Since the 1970s, mainstream games have prioritized themes of technomasculinity, violence, and competition. Until the mid 1980s, games included few female characters. When females began to appear, they tended to be hypersexualized or portrayed as damsels in distress. Female characters in the Mortal Kombat game (right), for example, are dressed in highly sexualized clothing featuring unrealistically large breasts and cinched waists (Cunningham, 2018; Vysotsky & Allaway, 2018). Or, in the Super Mario Brothers series, Princess Peach appears helpless and in need of rescue by the Mario brothers.

Since the 1970s, mainstream games have prioritized themes of technomasculinity, violence, and competition. Until the mid 1980s, games included few female characters. When females began to appear, they tended to be hypersexualized or portrayed as damsels in distress. Female characters in the Mortal Kombat game (right), for example, are dressed in highly sexualized clothing featuring unrealistically large breasts and cinched waists (Cunningham, 2018; Vysotsky & Allaway, 2018). Or, in the Super Mario Brothers series, Princess Peach appears helpless and in need of rescue by the Mario brothers.

A 2020 study of game characters and players on Twitch, Amazon’s popular live-streaming global platform, found that among the 27,564 characters studied, males (79%) vastly outnumber females (20.1%). This in spite of the fact that across all platforms boys and men constitute only 54% of players (Geena Davis Institute, 2021).

A 2020 study of game characters and players on Twitch, Amazon’s popular live-streaming global platform, found that among the 27,564 characters studied, males (79%) vastly outnumber females (20.1%). This in spite of the fact that across all platforms boys and men constitute only 54% of players (Geena Davis Institute, 2021).

The Twitch study focused on the portrayals of male characters. It found that 70.5% of male characters were shown in stereotypically masculine activities, with violence topping the list. Interestingly, in the set of games studied, white male characters perpetrated violence at a higher rate (55.4%) than male characters of color (30.9%). Further, white male characters were twice as likely both to carry a weapon as male characters of color and to kill at least one human (Geena Davis Institute, 2021). The concern is that the more hours gamers play, the more they tend to endorse the stereotypes embedded in the games (Blackburn & Scharrer, 2019).

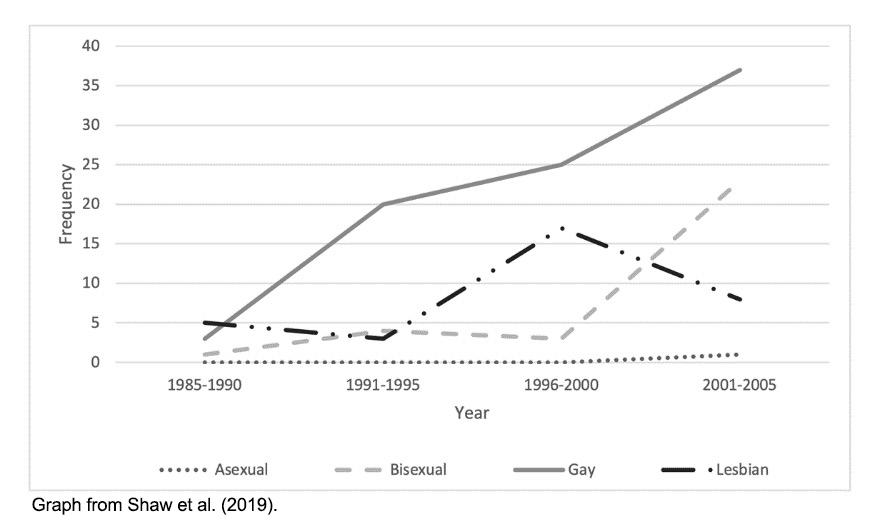

LGBTQIA+ characters do not fare much better. Out of the tens of thousands of games released in the past 70 years, by 2018 only 179 featured LGBTQIA+ characters (Greer, 2018). These queer characters are often cast as villains or are simply non-playable characters that blend into the background. Many games were also harmful: a 2019 survey of 163 video games released between 1985 and 2005 revealed that out of 283 LGBTQIA+ references, 29 were homophobic or transphobic (Shaw et al., 2019).

Often overlooked but equally harmful is the lack of in-game LGBTQIA+ communities. A study of 204 games found that most queer people figured as single characters amid a variety of heterosexual cisgender characters. These games rarely portrayed LGBTQIA+ relationships (Shaw et al., 2019). This failing is highlighted in the 2014 life-simulation game Tomodachi Life released by Nintendo. The game was criticized for not allowing characters to form same-sex relationships. When a bug made this temporarily possible, the creators “fixed” it immediately. In the words of the creators, they “never intended to make any form of social commentary with the launch of the game” (Kang & Yang, 2018).

Gender disparities are rife in games representing LGBTQIA+ characters. Gay men, for example, accounted for 56.6% of all LGBTQIA+ characters identified in a 2019 survey, whereas lesbian and bisexual characters comprise only 22% and 20.7% respectively. Racial representation was also a problem. White gay men in these games outnumbered gay men of color two to one. This misrepresents the racial makeup of the queer community and renders LGBTQIA+ people of color invisible (Shaw et al., 2019).

A “virtual census” published in 2009 analyzing 150 games across 9 platforms found that 80% of video game characters were white, as compared with 11% Black character, 3% Hispanic characters, 1% biracial characters, .09% Native America, and 5% Asian/Pacific Islander (Williams et al., 2009). The 2020 Twitch study found that 75% of characters were white compared to 25% characters of color. When present, characters of color are frequently stereotyped (Geena Davis Institute, 2021), leaving players of color poorly represented (Malkowsk & Russworm, 2017). Passmore & Mandryk (2018) found that players seek to self-represent in games. When building avatars for play, gamers sought digital representation for a diverse set of skin tones, hair textures and styles, facial physiognomy, body shape, and personalities. Providing a wider range character characteristics can drive inclusivity.

Method: Rethinking Language and Visual Representations

Games provide a virtual space where designers and players can experiment with ethnicity, gender and sexuality-experimentation that may be difficult or impossible in the real world (Turkle, 1997; Przybylski et al., 2021). A cross-sectional study of gamers found that—when given choices—54% of men and 68% of women engaged in “gender-swapping”; these players felt more freedom to experiment in game play than in real life (Hussain et al., 2008). Players might also engage with gender-ambiguous characters and play with other characteristics, such as race, age, height, etc. (Conrad et al., 2010; Harris et al., 2009). Challenging stereotypes has the potential to help remake real-world identities and behaviors, and may enhance diversity among players and game developers.

Challenging gender stereotypes may enhance diversity in video and online games, and potentially the gaming industry. This is important because games are increasingly spaces where young people engage in a significant portion of their socializing.

View General Method

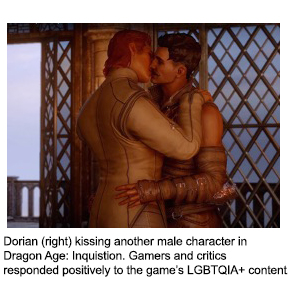

Games that feature pre-chosen characters need female, LGBTQIA+, and BIPOC characters that enjoy narrative parity with their majority male counterparts (Vella et al., 2020). For example, Dragon Age: Inquisition works to positively mainstream LGBTQIA+ characters (Villemez, 2020). In the game, Dorian, a powerful gay wizard, assists the main character in saving the fictional world of Thedas from a demon army. When he was younger, Dorian was forced by his father to undergo conversion therapy (through a process called “blood magic”). As in real life, this torture did not change Dorian’s sexuality.

Games that feature pre-chosen characters need female, LGBTQIA+, and BIPOC characters that enjoy narrative parity with their majority male counterparts (Vella et al., 2020). For example, Dragon Age: Inquisition works to positively mainstream LGBTQIA+ characters (Villemez, 2020). In the game, Dorian, a powerful gay wizard, assists the main character in saving the fictional world of Thedas from a demon army. When he was younger, Dorian was forced by his father to undergo conversion therapy (through a process called “blood magic”). As in real life, this torture did not change Dorian’s sexuality.

The presence of LGBTQIA+ characters is beginning to increase in games. But this representation is uneven (chart below).

Frequency of video game characters of different sexualities across 162 games released between 1985 and 2005. While LGBTQIA+ representation increased overall, lesbian representation saw a downward trend after the 2000s. The authors note that the unavailability of post-2005 data makes it impossible to judge whether this is an anomaly.

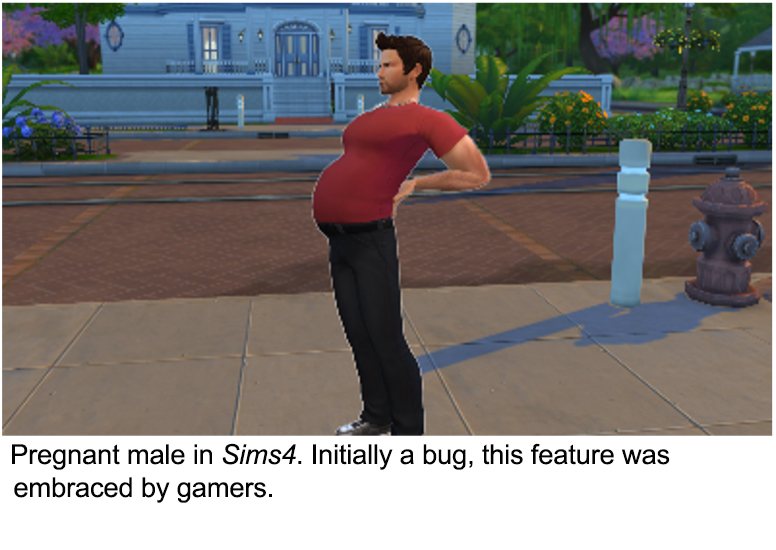

Frequency of video game characters of different sexualities across 162 games released between 1985 and 2005. While LGBTQIA+ representation increased overall, lesbian representation saw a downward trend after the 2000s. The authors note that the unavailability of post-2005 data makes it impossible to judge whether this is an anomaly.  Games that feature avatars can allow players to create their own from a wide range of customizable options for men, women, and non-binary individuals from different ethnic and racial backgrounds and sexual orientations. For example, in Sims 4, avatars are customizable across sex and physiology, allowing players to choose from a variety of voices, character traits, outfits, accessories, and cosmetics (Wood & Szymanski, 2020). Players can gender-swap their avatars; designated male avatars can have traditionally female accessories and characteristics, including the potential to become pregnant (right). Designated female Sims can feature traditionally male characteristics and accessories.

Games that feature avatars can allow players to create their own from a wide range of customizable options for men, women, and non-binary individuals from different ethnic and racial backgrounds and sexual orientations. For example, in Sims 4, avatars are customizable across sex and physiology, allowing players to choose from a variety of voices, character traits, outfits, accessories, and cosmetics (Wood & Szymanski, 2020). Players can gender-swap their avatars; designated male avatars can have traditionally female accessories and characteristics, including the potential to become pregnant (right). Designated female Sims can feature traditionally male characteristics and accessories.Method: Engineering Innovation Processes

Considering the following points may lead to games designed with dynamic gender norms:

1. In designing for “everybody,” game developers often design by default for white, heterosexual boys and men (Süngü, 2020; Sørensen et al., 2012; Rommes, 2006; Oudshoorn et al., 2004). Designing for “everybody” typically continues to exclude LGBTQIA+ gamers, gamers of color, non-binary people, and women.

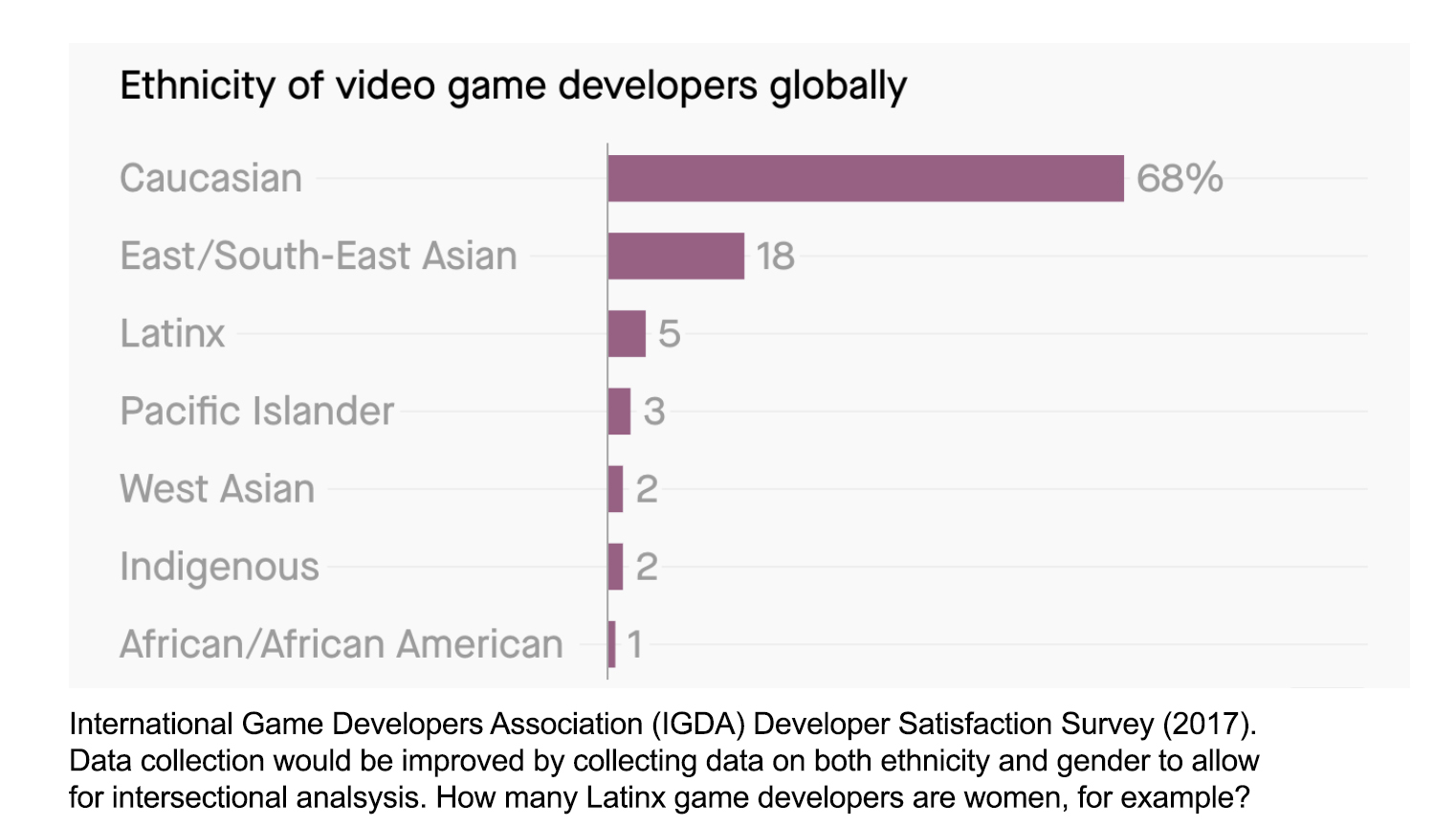

2. “I-Methodology"—where designers assume that users will like the same things they do—may also result in games for men. A 2021 survey of the gaming industry revealed that 61% of developers identify as men and 68% identify as heterosexual (IGDA, 2021). Further increasing diversity in the game industry will likely augment the number of well-represented characters of diverse backgrounds and identities (Smith, 2016).

3. User input from diverse players can be important (see Co-Creation and Participatory Research and Design.

a. Surveying users may produce inaccurate data due to reporting bias: People surveyed tend to report behaviors that conform to stereotypes. As a result, self-reports may generate inaccurate data that appear to support stereotypes.

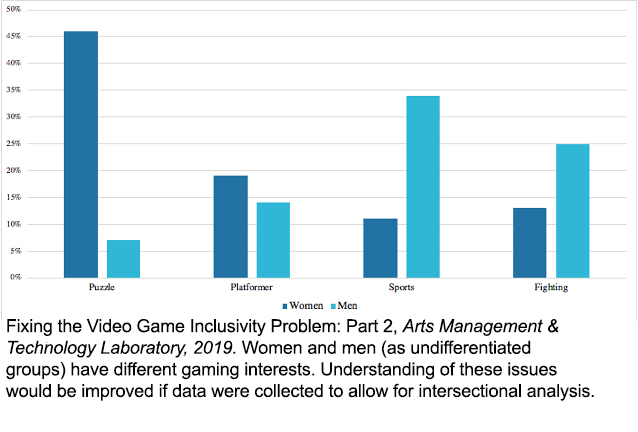

b. Objective measures of players’ play behaviors may lead to better design. This will help developers create game content that appeals to diverse audiences, as well as account for players that have different gaming behaviors (Veltri et al. 2014). For example, girls are more likely to play video games associated with cards, puzzles, and social interaction, while boys are more likely to play video games associated with fighting, shooting, sports, and fantasy role-play. Sandbox and simulation games appeal across genders (Cunningham, 2018).

c. Testing prototypes through questionnaires or direct feedback with intersectional gamers (e.g., queer Black people or Asian women) may enhance character development.

4. Intersectional approaches take into accountconsider group differences. Gamers are not all the same, and analyzing group heterogeneity may better capture the diversity of interests and tastes across broad populations. Not all women, for example, like the same games. Gaming is influenced by gender, ethnicity, race, sexual orientation, and their interactions. Age, educational level, geographic location (urban vs. rural and other factors also influence game preferences.

5. Building a diverse design team may broaden perspectives.

a. Including people from diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds, genders, and sexual orientations enhances creativity and innovation (Danilda et al., 2011; IGDA, 2022).

b. Simply including a wide range of developers, however, may not be enough. To maximize innovation, everyone on the design team needs to understand intersectional analysis. Teams should workshop narratives that encourage empathy and inclusivity while avoiding stereotypes (Gray, 2021).

View General Method

Game Developers

Gamers are often harassed. Women (38%) and LGBTQIA+ (35%) players reported the most online harassment, followed by Black (31%), Hispanic and Latinx (24%), and Asian (23%) players (Fiorellini, 2021). Gamers who feel harassed often find their own niche communities. The r/Gaymer and r/TransGamers forums on the social media site Reddit seek to provide spaces for LGBTQIA+ gamers to express their experiences (Fiorellini, 2021). Black Girl Gamers, a channel on Twitch, increases the visibility of Black women gamers. Increasing diversity among game developers coupled with increasing character diversity in video games may produce games and gaming communities that are inclusive and welcoming. These inclusive communities can work to “encourag[e] an equitable gaming environment…where marginalized players can become part of the center” (Skardzius, 2018).

While significant changes occurred in the gender makeup of developers, the 2021 race/ethnicity snapshot largely mirrored that of 2015. In 2021, 75% of survey respondents identified as White/Caucasian/European, 9% as Hispanic or Latino/Latina/Latinx, 7% as East Asian, 4% as Black/African American/African/Afro-Caribbean, and 4% as Aboriginal/Indigenous. In 2015 the figures were: 76% White/Caucasian/European, 7.3% Hispanic/Latino, 9% East Asian, 3% Black/African American/African/Afro-Caribbean, with Aboriginal/Indigenous not reported (IGDA, 2021; IGDA, 2015).

Further, the 2021 survey found that 29% of respondents identified as having one or more disabilities (IGDA, 2021). In 2015, 22% of respondents identified as having a disability (IGDA, 2015).

Demographics of game developers and players might be collected in an intersectional fashion. For example, how many gay developers are Asian? How many women developers are Black? This is difficult. IGDA itself reports 18 diversity categories. As in any research design, researchers need to be strategic to report statistics that, in this case, most impact game play.

Importantly, the IGDA has taken on the issue of inclusive design with their 2022 Inclusive Game Design and Development report, which advocates for inclusive design teams as well as diverse game content. The report moves step-by-step through the design process to advocate for sensitive inclusivity. “Any cultural references, inclusions or inspirations,” they state, “should be reviewed by an expert” to ensure that they are handled in a respectful fashion. If an expert is not already present on the team, a contracted consultant might be engaged.

While more remains to be done, this awareness of the relationship between team demographics, character and world building, and the needs of a wide range of players is a first step.

Conclusions

Design can promote social equity. Games, in particular, can be a catalyst for change in social norms, relations, and identities, and, eventually, in the gaming industry itself. Although current social identities and norms determine in part the kinds of games that are produced, culture itself is dynamic, and games can be used as an experimental space for creating new norms, relations, and identities.

Next Steps

- 1. Empirical data are required to understand differences and similarities in gaming behaviors, skills, and preferences across heterogeneous groups of players. Studies should include information about players' ethnicity, race, gender, sexual orientation, educational background, play experience, income level, regional location, and age to allow for intersectional analysis.

- 2. Developers might develop strategies to enhance flexibility in games, allowing games to become experimental spaces for changing social norms.

Works Cited

Anderson, C., Buckley, K., & Gentile, D. (2007). Violent Video Game Effects on Children and Adolescents: Theory, Research, and Public Policy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Burgess, M. C., Dill, K. E., Stermer, S. P., Burgess, S. R., & Brown, B. P. (2011). Playing with Prejudice: The Prevalence and Consequences of Racial Stereotypes In Video Games. Media Psychology, 14(3), 289-311.

Blackburn, G., & Scharrer, E. (2019). Video Game Playing and Beliefs about Masculinity among Male and Female Emerging Adults. Sex Roles, 80(5-6), 310-324.

Cameron, L. (2021). How the Black Girl Gamers Community Became a Lifeline. Wired, Nov 16. https://www.wired.com/story/black-girl-gamers-community/

Cunningham, C. M. (2018). Unbeatable? Debates and Divides in Gender and Video Game Research. Communication Research Trends, 37(3), 4–29.

Danilda, I., & Thorslund, J. (Eds.). (2011). Innovation & Gender. Stockholm: VINNOVA Information.

Dill, K. E., Brown, B. P., & Collins, M. A. (2008). Effects of Exposure to Sex-Stereotyped Video Game Characters on Tolerance of Sexual Harassment. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(5), 1402-1408.

Dill, K. E., & Burgess, M. C. (2013). Influence of Black Masculinity Game Exemplars on Social Judgments. Simulation & Gaming, 44(4), 562-585.

Entertainment Software Association (ESA). (2021). 2021 Essential Facts about the Video Game Industry, https://www.theesa.com/resource/2021-essential-facts-about-the-video-game-industry/.

Fiorellini, N. (2021). Venn Diagram of LGBTQ++ and Gaming Communities Goes Here. JSTOR Daily: Arts & Culture. Retrieved November 29, 2021, from https://daily.jstor.org/venn-diagram-of-LGBTQ+-and-gaming-communities-goes-here/.

Flanagan, M., & Nissenbaum, H. (2007). A Game Design Methodology to Incorporate Social Activist Themes. In Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) (Ed.), Proceedings of the 2007 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 181-190. New York: ACM Press.

Geena Davis Institute. (2021). The Double-Edged Sword of Online Gaming: An Analysis of Masculinity in Video Games and the Gaming Community. https://seejane.org/wp-content/uploads/gaming-study-2021-7.pdf.

Gray, R. (2021). GLAAD Media Awards and How Outstanding Video Games Made the Cut. Gayming: The Home of Queer Geek Culture. Retrieved December 7, 2021, from https://gaymingmag.com/2021/04/glaad-media-awards-and-how-outstanding-video-games-made-the-cut/

Greer, S. (2018). Queer Representation in Games Isn't Good Enough, But It Is Getting Better. Gamesradar. Retrieved December 7, 2021, from https://www.gamesradar.com/queer-representation-in-games-isnt-good-enough-but-it-is-getting-better/

Greitemeyer, T., & Osswald, S. (2010). Effects of Prosocial Video Games on Prosocial Behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98 (2), 211-221.

Hagan, E. (2017). Why Visibility Matters. Psychology Today. Retrieved December 7, 2021, from www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/all-things-LGBTQ+/201711/why-visibility-matters

Herman, L. (1999). Phoenix: The Rise and Fall of Video Games, Second Edition. Union, New Jersey: Rolenta Press.

IGDA (International Game Developers Association). (2022). Inclusive Game Development and Development. https://igda-website.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/08124833/Inclusive-Game-Design-and-Development.pdf.

IGDA (International Game Developers Association). (2021). Developer Satisfaction Survey 2021: A Summary Report. IGDA.org. https://igda-website.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/18113901/IGDA-DSS-2021_SummaryReport_2021.pdf.

IGDA (International Game Developers Association). (2015). Developer Satisfaction Survey 2021: A Summary Report. IGDA.org. https://igda-website.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/21174418/IGDA_DSS_2015-Summary_Report.pdf.

Kang, Y., & Yang, K. C. (2018). The Representation (or the Lack of It) of Same-Sex Relationships in Digital Games. In Queerness in Play. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham., 57-79.

Malkowski, J & Russworm, T. (Eds.) (2017). Gaming Representation: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in Video Games. Indiana University Press.

Nielsen Survey. (2020). Nielsen Games 360 Survey, reported in Out, August 7. https://www.out.com/tech/2020/8/07/10-percent-gamers-are-LGBTQ+-nielsen-study-shows.

Oudshoorn, N., Rommes, E., & Stienstra, M. (2004). Configuring the User as Everybody: Gender and Design Cultures in Information and Communication Technologies. Science, Technology and Human Values, 29 (1), 30-63.

Passmore, C. J., & Mandryk, R. (2018, October). An about face: Diverse Representation in Games. In Proceedings of the 2018 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, 365-380).

Przybylski, A. K., Weinstein, N., Murayama, K., Lynch, M. F., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). The Ideal Self At Play: The Appeal Of Video Games that Let You Be All You Can Be. Psychological Science, 23(1), 69-76.

Rommes, E. (2006). Gender Sensitive Design Practices. In Trauth, E. (Ed.), Gender and Information Technology, Volume 1, pp. 675-681. Hershey: Idea Group Reference.

Shaw, A., Lauteria, E., Yang, H., Persaud, C., & Cole, A. (2019). Counting Queerness in Games: Trends in LGBTQ+ Digital Game Representation, 1985‒2005. International Journal of Communication, 13, 26. Retrieved from https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/9754/2611

Skardzius, K. (2018). “Playing with Pride: Claiming Space Through Community Building in World of Warcraft.” Pp. 175–92 in Woke Gaming: Digital Challenges to Oppression and Social Injustice, edited by K. L. Gray and D. J. Leonard. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Sørensen, K., Rommes, E., & Faulkner, W. (Eds.). (2012). Technologies of Inclusion: Gender in the Information Society. Trondheim: Tapir Academic Press

Stefansdóttir, S., & Gíslason, H. (2008). Design Innovation for Gender Equality. Oslo: DIG Equality.

Süngü E. (2020). Gender Representation and Diversity in Contemporary Video Games. In Barbaros B. (Ed.) Game User Experience and Player-Centered Design, pp. 379-392. Springer Verlag.

Vella, K., Klarkowski, M., Turkay, S., & Johnson, D. (2020). Making Friends in Online Games: Gender Differences and Designing for Greater Social Connectedness. Behaviour and Information Technology, 39(8), 917–934.

Villemez, J. (2020). Press A, Be Gay: LGBTQ+ Representation in Video Games. Philadelphia Gay News. https://epgn.com/2020/09/30/press-a-be-gay-LGBTQ+-representation-in-video-games/.

Veltri, N., Krasnova, H., Baumann, A., & Kalayamthanam, N. (2014). Gender Differences in Online Gaming: A Literature Review. Twentieth Americas Conference on Information Systems, 1-11.

Vysotsky, S., & Allaway, J. (2018). The Sobering Reality of Sexism in the Video Game Industry. Woke Gaming: Digital Challenges to Oppression and Social Injustice, 101-118.

Westcott, K., Arbanas, J., Arkenberg, C., Auxier, B. (2021). Streaming Video on Demand, Social Media, and Gaming Trends. Deloitte. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/technology/svod-social-media-gaming-trends.html

Williams, D., Martins, N., Consalvo, M., & Ivory, J. D. (2009). The Virtual Census: Representations of Gender, Race and Age in Video Games. New Media & Society, 11(5), 815–834.

Wood, S. M., & Szymanski, A. (2020). “The Me I Want You to See”: The Use of Video Game Avatars to Explore Identity in Gifted Adolescents. Gifted Child Today, 43(2), 124-134.

Yang, G. S., Gibson, B., Lueke, A. K., Huesmann, L. R., & Bushman, B. J. (2014). Effects of Avatar Race in Violent Video Games on Racial Attitudes and Aggression. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5(6), 698-704.

Analyzing Gender is a basic method. Video games are an interesting area for application. During the past fifty years, most video game inventors, programmers, and players have been men. In 1962, Steve Russell at MIT created Spacewar!, the first widely-distributed software video game. Until games were commercialized in 1971, game developers and players were primarily computer scientists, electrical engineers, and their students—games were highly masculinized, promoting fighting, killing, and shooting.

Gendered Innovation:

Scholars are interested in how games—and the cultures that form around them—influence players' real-world behaviors, and vice-versa. Researchers have found that games embed "beliefs within their representation systems and structures, whether designers intend them or not."

Gendered Innovations:

- 1. Games may serve as catalysts for change. Analyzing Gender has led to understanding how games provide a virtual space where designers and players can explore gender identities and behaviors. Challenging gender stereotypes may enhance diversity in video and online games, and potentially the gaming industry itself. This is important because games are increasingly spaces where young people socialize.

- 2. Designers can create flexible, gender-mixed games. By analyzing sex and gender throughout engineering innovation processes, researchers have looked beyond stereotypes to understand the complex patterns of young women's and young men's video gaming—patterns that are influenced by factors beyond sex, such as age, experience, and geographic location.