Sex refers to biology; however, there is no single, universally agreed-upon set of guidelines for defining sex. Sex is complex, dynamic, context-dependent, and interacts with gender and other social factors (Ritz & Greaves, 2022; Dubois et al., 2025).

Graphic by Amanda Montañez, Beyond XX and XY: The Extraordinary Complexity of Sex Determination.

Scientific American, 317 (2017). With permission.

Data collection. The U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine recommend methods for data collection for the term “sex” (National Academies, 2022).

Take care not to overemphasize sex differences.

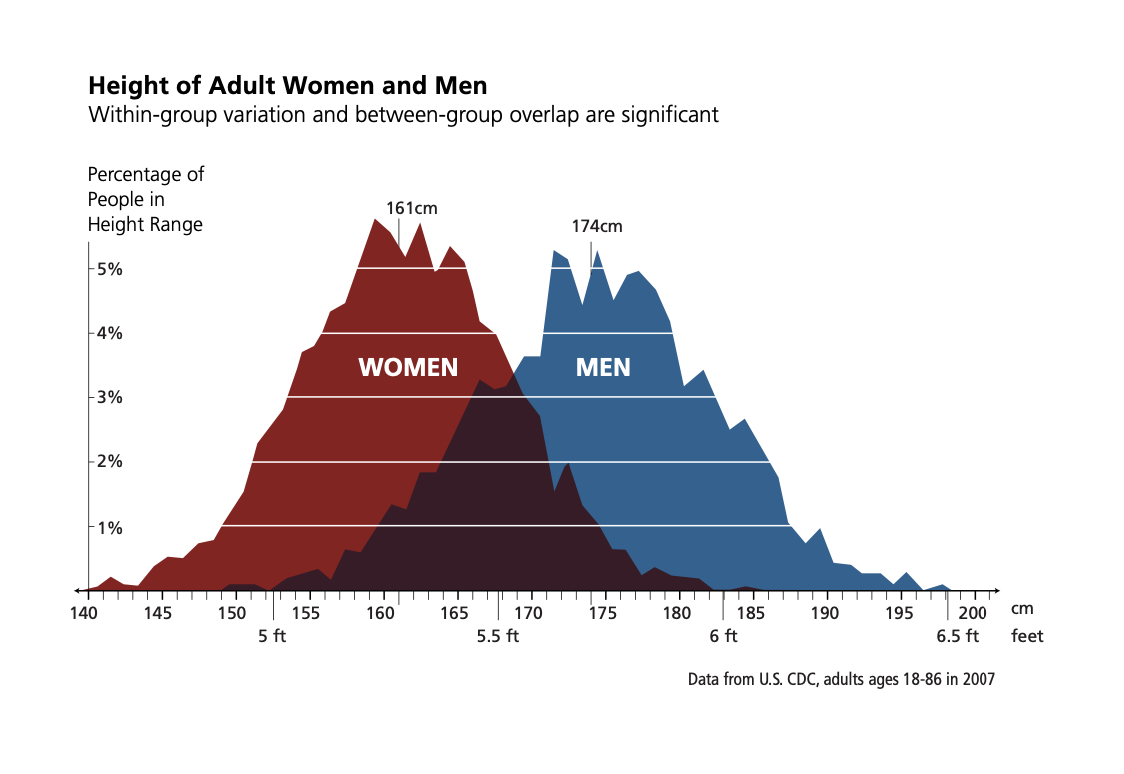

Sex is not neatly binary; there is considerable within-group variation and between-group overlap (see figure below). Take, for example, height. In the US, women are shorter than men on average, but about 3% of women are taller than the average man, and 6% of men are shorter than the average woman. The height difference between the average woman and man is less than the height difference between a 90th percentile and 10th percentile woman, or the difference between a 90th and 10th percentile man.

Works Cited

Ainsworth, Clair. (2015). Sex Redefined. Nature 518 (7539), 288-291.

Barresi, M. & Gilbert, S. (2023). Developmental Biology, 13th Edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cell, Editorial Team. (2024). Special Section on Sex and Gender, 187, 1513-1357.

DuBois, L. Z., Ritz, S. A., McCarthy, M. M., & Kaiser Trujillo, A. (2025). Sex and Gender: Toward Transforming Scientific Practice. Frankfurt: Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies.

DuBois, L. Z., & Shattuck‐Heidorn, H. (2021). Challenging the binary: Gender/sex and the bio‐logics of normalcy. American Journal of Human Biology, 33(5), e23623.

Fausto-Sterling, A. (2000). Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality. New York: Basic Books.

Fausto-Sterling, A. (2012). Sex/Gender: Biology in a Social World. New York: Routledge.

Jarne, P. & Auld, J. R. (2006). Animals mix it up too: the distribution of self-fertilization among hermaphroditic animals. Evolution 60, 1816-1824.

Jones, T. (2018). Intersex studies: A systematic review of international health literature. Sage Open 8(2), 2158244017745577.

Kessler, S. (1998). Lessons from the Intersexed. News Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Linder, A., & Svedberg, W. (2019). Review of average sized male and female occupant models in European regulatory assessment tests and European laws: gaps and bridging suggestions. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 127, 156-162.

Montañez, Amanda. (2017). Beyond XX and XY: The extraordinary complexity of sex determination. Scientific American, 317.

Munday, P.L., Buston, P.M. and Warner, R.R., 2006. Diversity and flexibility of sex-change strategies in animals. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 21(2), pp.89-95.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2022). Measuring Sex, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Nature, Editor. (2024). Special Section on Sex and Gender, 629, 7-8.

Ritz, S. A., & Greaves, L. (2022). Transcending the Male–Female Binary in Biomedical Research: Constellations, Heterogeneity, and Mechanism When Considering Sex and Gender. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 4083.

Tiffany, K. Period-tracking apps are not for women. Vox, November 16, 2018.

Weber, R. N. (1997). Manufacturing Gender in Commercial and Military Cockpit Design. Science, Technology, & Human Values 22 (2): 235-253.