Sex, Gender, & Intersectional Analysis

Case Studies

- Science

- Health & Medicine

- Chronic Pain

- Colorectal Cancer

- Covid-19

- De-Gendering the Knee

- Dietary Assessment Method

- Gendered-Related Variables

- Heart Disease in Diverse Populations

- Medical Technology

- Nanomedicine

- Nanotechnology-Based Screening for HPV

- Nutrigenomics

- Osteoporosis Research in Men

- Prescription Drugs

- Systems Biology

- Engineering

- Assistive Technologies for the Elderly

- Domestic Robots

- Extended Virtual Reality

- Facial Recognition

- Gendering Social Robots

- Haptic Technology

- HIV Microbicides

- Inclusive Crash Test Dummies

- Human Thorax Model

- Machine Learning

- Machine Translation

- Making Machines Talk

- Video Games

- Virtual Assistants and Chatbots

- Environment

Nanotechnology-Based Screening for HPV: Rethinking Research Priorities and Outcomes

Abstract

The Gendered Innovations project was asked by the European Commission to analyze several of its Framework Programme 7 (FP7) projects. This case study examines the "Enhanced Sensitivity Nanotechnology-Based Multiplexed Bioassay Platform for Diagnostic Applications" (NANO-MUBIOP) project. We identify gendered innovations, methods of sex and gender analysis, and points of potential "value added."

The Challenge

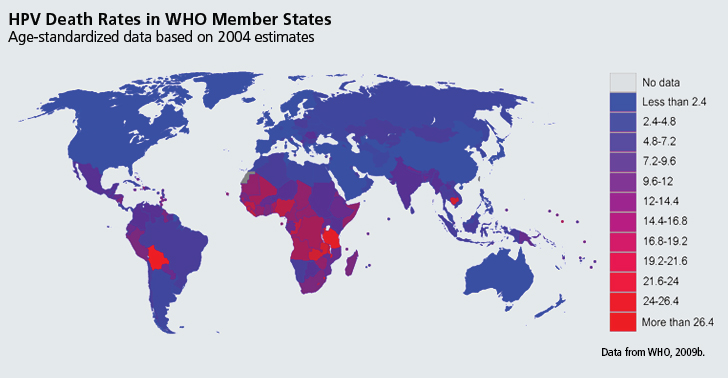

Infection with Human Papillomavirus (HPV) "is estimated to cause […] 100% of cervical cancer cases," and contributes to the incidence of other cancers affecting both women and men, including anal cancer, oral and oropharyngeal cancers, and cancers of the genitals (WHO, 2008b). Worldwide, cervical cancer causes about 275,000 deaths per year - 80% in countries with limited medical resources (Sankaranarayanan et al., 2012). Existing HPV tests offer good sensitivity and specificity, but are rarely used in developing countries due to cost (Cuzick et al., 2008). A low-cost, high-performance test could improve healthcare in developing countries.

Method: Rethinking Research Priorities and Outcomes

In designing a new diagnostic technology, the NANO-MUBIOP project prioritized characteristics that would encourage adoption in diverse low-resource areas, such as Latin America and the Caribbean, sub-Saharan Africa, Melanesia, and South-Central and South-East Asia. These include technical characteristics - such as the ability to differentiate between specific types of HPV, which differ in epidemiology and oncogenicity - and practical, logistical characteristics - such as low overhead cost and simple implementation.

Gendered Innovations:

Developing a Low-Cost HPV Screening Test. NANO-MUBIOP seeks to develop a platform for inexpensive HPV testing.

Potential Value Added to Future Research through the Future Application of Gendered Innovations Methods

- 1. Identifying potential users of the NANO-MUBIOP platform

- 2. Understanding the causes of poor cervical cancer screening coverage

Background: The European Union Framework Programme 7 (FP7) Enhanced Sensitivity Nanotechnology-Based Multiplexed Bioassay Platform for Diagnostic Applications and Existing Strategies for Combating Cervical Cancer

Gendered Innovation 1: Developing a Low-Cost HPV Screening Test

Potential Value Added to Future Research through the Application of Gendered Innovations Methods

Potential Value Added 1: Identifying Potential Users

Method: Intersectional Approaches

Potential Value Added 2: Understand the Causes of Poor Cervical Cancer Screening

Method: Rethinking Research Priorities and Outcomes

Conclusions

The Challenge

Approximately 40 types of HPV are known to infect the genital tract (Trottier et al., 2009). Of these, 13 are classified as "high risk" for causing cervical cancer (Bhatla et al., 2010; Muñoz et al., 2003). HPV infection causes an estimated 100% of cervical cancer cases, and contributes to the incidence of other cancers affecting men specifically (penile cancer), women (vulvar cancer), and both women and men (anal cancer and several types of oral cancers) (WHO, 2008b).

The World Health Organization (WHO) has underscored the importance of screening, stating that "the introduction of HPV vaccine should not undermine or divert funding from effective screening programmes for cervical cancer" (WHO, 2009). Recent studies conducted in India and China indicate that affordable HPV DNA testing could significantly lower the incidence of advanced cervical cancer and mortality rates in low resource areas (Sankaranarayanan et al., 2009; Qiao et al., 2008). It should be noted that, like other screening programs, NANO-MUBIOP seeks to develop a platform for testing; it does not itself either prevent or treat HPV.

Background

The European Commission Framework Programme 7 (FP7) "Enhanced Sensitivity Nanotechnology-Based Multiplexed Bioassay Platform for Diagnostic Applications" (NANO-MUBIOP) and Existing Strategies for Combating Cervical Cancer

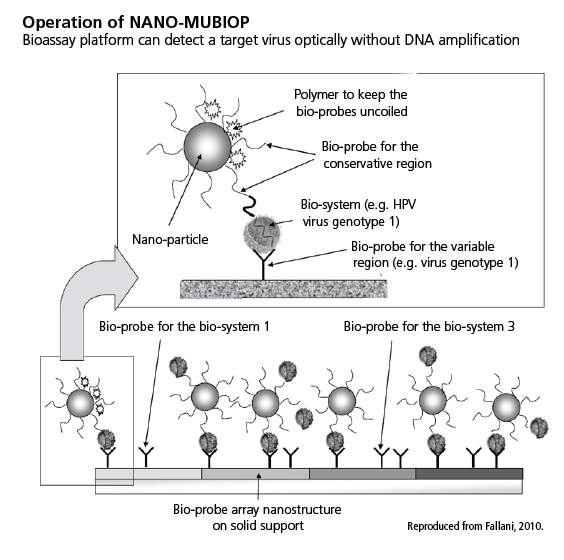

The NANO-MUBIOP project seeks to develop a bioassay platform, using nanoparticles, that is capable of detecting a target virus (for example, HPV) without DNA amplification. This platform, in an early stage of development, is planned as a heterogeneous bioassay method employing DNA probes specific for different DNA targets. Probes are arrayed on a solid substrate (slide). These slides would be exposed to DNA-containing analytes in the presence of carboxylated silica nanoparticles that would themselves be functionalized with generic probes complementary to DNA sequences in common to all DNA bio-targets (Fallani, 2010; Tóth et al., 2010; Tóth et al., 2012). The binding of these nanoparticles to DNA analytes would encourage and stabilize DNA binding to the probes on-substrate. Nanoparticles would then be detected optically—see schematic diagram on right showing the operation of NANO-MUBIOP.

The NANO-MUBIOP project seeks to develop a bioassay platform, using nanoparticles, that is capable of detecting a target virus (for example, HPV) without DNA amplification. This platform, in an early stage of development, is planned as a heterogeneous bioassay method employing DNA probes specific for different DNA targets. Probes are arrayed on a solid substrate (slide). These slides would be exposed to DNA-containing analytes in the presence of carboxylated silica nanoparticles that would themselves be functionalized with generic probes complementary to DNA sequences in common to all DNA bio-targets (Fallani, 2010; Tóth et al., 2010; Tóth et al., 2012). The binding of these nanoparticles to DNA analytes would encourage and stabilize DNA binding to the probes on-substrate. Nanoparticles would then be detected optically—see schematic diagram on right showing the operation of NANO-MUBIOP.

Biological samples are to be directly analyzed by the NANO-MUBIOP platform, without previous amplification through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or other methods. Functionalizing a substrate with multiple types of probes in specific regions could allow identification of multiple DNA targets—for example, variant DNA sequences in specific HPV types (Tóth et al., 2011; Liguri et al., 2010).

Comprehensive cervical cancer management includes screening, which might be performed with NANO-MUBIOP. Screening is vital because, with early detection, cervical cancer is highly treatable. In resource-rich countries, where cervical cancer is generally detected and treated in early stages, survival rates are much higher than in resource-poor countries, where detection generally occurs later and treatment is delayed or unavailable (Parkin et al., 2006). Many screening tests are in use. The chart at left places NANO-MUBIOP in relation to cervical cancer prevention and screening--click to view.

Gendered Innovation 1: Developing a Low-Cost HPV Screening Test

NANO-MUBIOP researchers are working to develop an inexpensive HPV test. HPV tests exist, but high cost and complexity have limited adoption. NANO-MUBIOP seeks to provide:

- 1. Low cost, on both a per-test basis and in terms of overhead for infrastructure needed to distribute and process tests (Trisolini et al., 2008a).

- 2. Minimal requirements for instrumentation and skilled operators, particularly in comparison to cytological and DNA methods, although a scanning or reading system will be needed (Trisolini et al., 2008a).

- 3. Rapid test results, especially when compared to other DNA testing methods (Trisolini et al., 2008a).

- 4. The ability to discriminate between specific HPV types (Trisolini et al., 2008a).

- 5. The ability to test samples from men as well as women (Fallani, 2010).

Potential Value Added to Future Research through the Application of Gendered Innovations Methods

Potential Value Added 1: Identifying Potential Users

Researchers might analyze factors intersecting with sex and gender to identify potential users of NANO-MUBIOP, and subsequently rethink research priorities and outcomes to design according to the needs of this target group—see Methods.

Method: Intersectional Approaches

HPV causes morbidity and mortality in both women and men worldwide, but the burden of HPV-related disease is unevenly distributed according to sex and geographic location:

- 1. HPV-Related Diseases by Sex and Type: The majority of HPV-attributable cancers, an estimated 94%, occur in women because HPV causes more cases of cervical cancer than other cancer types (WHO, 2008b).

Chart produced with data from Parkin et al., 2006.

- 2.HPV-Related Diseases by Location: The majority of HPV-attributable cancers, an estimated 83%, occur in the developing world (Parkin et al., 2006). Deaths from cervical cancer are especially concentrated in resource-poor regions:

Potential Value Added 2: Understand the Causes of Poor Cervical Cancer Screening

NANO-MUBIOP researchers seek to develop an HPV screening platform that can be used in developing countries (Trisolini et al., 2008a). Understanding the needs of this user group may require a further Method—see below.

Regardless of cause, the heterogeneity of HPV type prevalence underscores the potential usefulness of a test able to detect multiple types.Method: Rethinking Research Priorities and Outcomes

Cervical cancer screening could be enhanced through four specific innovations:

- 1. Reducing Costs to Increase Availability: Cervical cancer screening is highly cost-effective in both developed and developing countries—that is, the cost per life-year saved is very low in comparison to many other medical interventions (WHO, 2011; Goldhaber-Fiebert et al., 2008). However, cost remains an obstacle to adoption in developing countries; women in poor countries are much less likely to be screened than women in wealthier countries (Gakidou et al., 2008).

Cervical cancer screening—whether performed by visual methods, cytological methods, or HPV testing—has costs associated with staff, "disposable supplies" (consumables), and "equipment and laboratory use" (instrumentation and infrastructure) (Goldie et al., 2005). NANO-MUBIOP researchers are seeking to reduce costs on all three fronts by creating a low-cost test that does not require skilled labor for implementation (as cytology tests do) and does not require access to a sophisticated molecular biology laboratory (as amplification-based HPV DNA tests often do) (Trisolini et al., 2008a).

- 2. Automating Testing to Improve Quality Control: In countries where cervical cancer screening is available, healthcare can be compromised by low quality of screening services. In developing countries, about 45% of women have access to some form of cervical cancer screening, but only 19% have access to screening defined as effective (Gakidou et al., 2008). Quality control is particularly challenging for cytology-based tests (pap smears and liquid cytology).The labor-intensive nature of cytological screening and the extensive training needed to interpret test results can substantially compromise screening quality (Cuzick et al., 2008). NANO-MUBIOP researchers aim to overcome these obstacles by introducing an automated test (Trisolini et al., 2008c).

- 3. Accelerating Testing to Allow Rapid Follow-Up: Conventional cervical cancer screening programs—particularly those based on cytology and HPV DNA testing—can have long follow-up times. Follow-up rates are often low, especially in developing countries with limited communication and transportation infrastructure (Bosch et al., 2008).

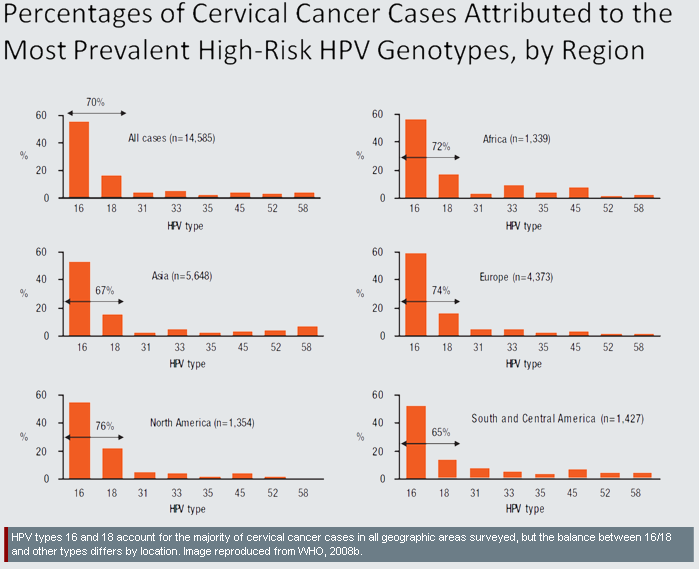

- 4. Identifying HPV Subtypes to Enhance Specificity: Worldwide, there are modest differences in the burden of cervical cancer attributable to specific HPV types. For example, HPV types 16 and 18 cause 76% of cases in North America, but only 65% of cases in South and Central America, with intermediate values in other regions:

- The causes of observed differences in type-prevalence are not fully understood (Clifford et al., 2005). Some possibilities include:

- A. Immunogenetics: People in different geographic areas may have different genetic polymorphisms which affect their susceptibility or resistance to specific HPV types (Hildesheim et al., 2002).

- B. Prevalence of Other Infectious Diseases: Non-HPV infectious diseases may influence the risk of infection with specific HPV types. For example, HIV-related immune deficiency raises the risk of HPV-16 infection less than it raises the risk of infection with other HPV types (Strickler et al., 2003). This might explain why HPV types other than HPV-16 are a more important cause of cervical cancer in Africa (where HIV is relatively prevalent) than in Europe (where HIV is less prevalent) (Clifford et al., 2005).

- C. Prevalence of Non-Infectious Diseases and Conditions: Malnutrition may contribute to higher incidence of non-HPV-16 types in resource-poor areas (Clifford et al., 2005).

In addition to geographic differences in prevalence, different types of HPV vary in their propensity to cause specific types of cervical cancer (Dahlström et al., 2010). For example, "HPV-18 is more often associated with difficult to detect or visualize lesions in the endocervical canal" than certain other types (Cuzick et al., 2008). For these reasons, detection of specific HPV types has potential therapeutic value, and NANO-MUBIOP researchers have made multiplexing a key development priority (Trisolini et at., 2008a).

Conclusion

The NANO-MUBIOP project has identified key needs for HPV testing in both the developed and developing worlds. Although still in development, NANO-MUBIOP seeks to produce a test which can detect HPV reliably and rapidly in both women and men, and are concentrating on using automation to minimize the high personnel costs typical of existing HPV tests. NANO-MUBIOP researchers have produced laboratory prototypes, but much work remains to be done before the platform can be clinically validated (Fallani, 2010).

Works Cited

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Infectious diseases (2012). HPV vaccine recommendations. Pediatrics, 129 (3), 602-605.

Arbyn, M., Weiderpass,. E., & Capocaccia, R. (2012). Effect of Screening on Deaths from Cervical Cancer in Sweden. British Medical Journal, 344, e804.

Arbyn, M., Castellsagué, X., De Sanjosé, S., Bruni, L., Saraiya, M., Bray, F., & Ferlay, J. (2011). Worldwide Burden of Cervical Cancer in 2008. Annals of Oncology, 22 (12), 2675-2686.

Arbyn, M., Anttila, A., Jordan, J., Ronco, G., Schenck, U., Segnan, N., Wiener, H., Herbert, A., & Von Karsa, L. (2010). European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Cervical Cancer Screening, Second Edition—Summary Document. Annals of Oncology, 21 (3), 448-458.

Arbyn, M., Raifu, A., Weiderpass, E., Bray, F., & Anttila, A. (2009). Trends of Cervical Cancer Mortality in the Member States of the European Union. European Journal of Cancer, 45 (15), 2640-2648.

Bernard, H., Burk, R., Chen, Z., Van Doorslaer, K., Zur Hausen, H., & De Villiers, E. (2010). Classification of Papillomaviruses (PVs) Based on 189 PV Types and Proposal of Taxonomic Amendments. Virology, 401 (1), 70-79.

Bhatla, N., Classen, M., Denny, L., Fagan, J., Franceschi, S., Gueye, S., Jalloh, M., Mohammed, Z., Ngoma, T., Niang, L., Prinz, C., Quek, S., Torode, J., Wiersma, S., Wittet, S., You, W., & Hausen, H. (2010). Protection Against Cancer-Causing Infections - World Cancer Campaign 2010. Geneva: International Union Against Cancer (UICC).

Castellsagué, X., De Sanjosé, S., Aguado, T., Louie, K., Bruni, L., Muñoz, J., Diaz, M., Irwin, K., Gacic, M., Beauvais, O., Albero, G., Ferrer, E., Byrne, S., & Bosch, F. (2007). HPV and Cervical Cancer in the World: 2007 Report. Vaccine, 25 (S3), 1-241.

Castellsagué, X., & Muñoz N. (2003). Chapter 3: Cofactors in Human Papillomavirus Carcinogenesis—Role of Parity, Oral Contraceptives, and Tobacco Smoking. Journal of the National Cancer Institute: Monographs, 20 (31), 20-28.

Chin-Hong, P., Berry, J., Cheng, S., Catania, J., Da Costa, M., Darragh, T., Fishman, F., Jay, N., Pollack, L., & Palefsky, J. (2008). Comparison of Patient- and Clinician-Collected Anal Cytology Samples to Screen for Human Papillomavirus–Associated Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia in Men Who Have Sex with Men. Annals of Internal Medicine, 149 (5), 300-306.

Chin-Hong, P., Vittinghoff, E., Cranston, R., Buchbinder, S., Cohen, D., Colfax, G., Da Costa, M., Darragh, T., Hess, E., Judson, F., Koblin, B., Madison, M., & Palefsky, J. (2004). Age-Specific Prevalence of Anal Human Papillomavirus Infection in HIV-Negative Sexually Active Men Who Have Sex with Men: The EXPLORE Study. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 190 (12), 2070-2076.

Clifford, G., Gallus, S., Herrero, R., Muñoz, N., Snijders, P., Vaccarella, S., Anh, P., Ferreccio, C., Hieu, N., Matos, E., Molano, M., Rajkumar, R., Ronco, G., De Sanjosé, S., Shin, H., Sukvirach, S., Thomas, J., Tunsakul, S., Meijer, C., & Franceschi, S. (2005). Worldwide Distribution of Human Papillomavirus Types in Cytologically Normal Women in the International Agency for Research on Cancer HPV Prevalence Surveys: A Pooled Analysis. The Lancet, 366 (9490), 991-998.

Cuzick, J., Arbyn, M., Sankaranarayanan, R., Tsu, V., Ronco, G., Mayrand, M., Dillner, J., & Meijer, C. (2008). Overview of Human Papillomavirus-Based and Other Novel Options for Cervical Cancer Screening in Developed and Developing Countries. Vaccine, 26 (S10), K29-K41.

Dahlström, L., Ylitalo, N., Sundström, K., Palmgren, J., Ploner, A., Eloranta, S., Sanjeevi, C., Andersson, S., Rohan, T., Dilner, J., Adami, H., & Sparén, P. (2010). Prospective Study of Human Papillomavirus and Risk of Cervical Adenocarcinoma. International Journal of Cancer, 127 (8), 1923-1930.

Denny, L., Quinn, M., & Sankaranarayanan, R. (2006). Chapter 8: Screening for Cervical Cancer in Developing Countries. Vaccine, 24 (S3), S71-S77.

Denny, L., Kuhn, L., De Souza, M., Pollack, A., Dupree, W., & Wright, T. (2005). Screen-and-Treat Approaches for Cervical Cancer Prevention in Low-Resource Settings: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 294 (17), 2173-2181.

De Vuyst, J., Clifford, G., Li, N., & Franceschi, S. (2009). HPV Infection in Europe. European Journal of Cancer, 45 (15), 2632-2639.

Dunne, E., Unger, E., Sternberg, M., McQuillan, G., Swan, D., Patel, S., & Markowitz, L. (2007). Prevalence of HPV Infection among Females in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association, 297 (8), 813-819.

Dunne, E., Nielson, C., Stone, K., Markowitz, L., & Giuliano, A. (2006). Prevalence of HPV Infection among Men: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 194 (8), 1044-1057.

Fallani, M. (2010). Periodic Report - NANO-MUBIOP (Enhanced Sensitivity Nanotechnology-Based Multiplexed Bioassay Platform for Diagnostic Applications). Brussels: Community Research and Development Information Service (CORDIS). PDF.

Franceschi, S., Herrero, R., Clifford, G., Snijders, P., Arslan, A., Anh, P., Bosch, F., Ferreccio, C., Hieu, N., Lazcano-Ponce, E., Matos, E., Molano, M., Qiao, Y., Rajkumar, R., Ronco, G., De Sanjosé, S., Shin, H., Sukvirach, S., Thomas, J., Meijer, C., & Muñoz, N. (2006). Variations in the Age-Specific Curves of Human Papillomavirus Prevalence in Women Worldwide. International Journal of Cancer, 119 (11), 2677-2684.

Franco, E., Mahmud, S., Tot, J., Ferenczy, A., & Coutlée, F. (2009). The Expected Impact of HPV Vaccination on the Accuracy of Cervical Cancer Screening: The Need for a Paradigm Change. Archives of Medical Research, 40 (6), 478-485.

Gakidou, E., Nordhagen, S., & Obermeyer, Z. (2008). Coverage of Cervical Cancer Screening in 57 Countries: Low Average Levels and Large Inequalities. Public Library of Science (PLoS) Medicine, 5 (6), e132.

García-Closas, R., Castellsagué, X., Bosch, X., & González, C. (2005). The Role of Diet and Nutrition in Cervical Carcinogenesis: A Review of Recent Evidence. International Journal of Cancer, 117 (4), 629-637.

Giuliano, A., Lu, B., Nielson, C., Flores, R., Papenfuss, M., Lee, J., Abrahamsen, M., & Harris, R. (2008). Age-Specific Prevalence, Incidence, and Duration of Human Papillomavirus Infections in a Cohort of 290 US Men. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 198 (6), 827-835.

Giuliano, A., Sedjo, R., Roe, S., Harris, R., Baldwin, S., Papenfuss, M., Abrahamsen, M., & Inserra, P. (2002). Clearance of Oncogenic Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection: Effect of Smoking (United States). Cancer Causes and Control, 13 (9), 839-846.

GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). (2012). CERVARIX Full Prescribing Information. Research Triangle Park, North Carolina: GSK. PDF.

Goldhaber-Fiebert, J., Stout, N., Salomon, J., Kuntz, K., & Goldie, S. (2008). Cost-Effectiveness of Cervical Cancer Screening with Human Papillomavirus DNA Testing and HPV-16,18 Vaccination. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 100 (5), 308-320.

Goldie, S., Gaffikin, L., Goldhaber-Fiebert, J., Gordilo-Tobar, A., Levin, C., Mahé, C., & Wright, T. (2005). Cost-Effectiveness of Cervical Cancer Screening in Five Developing Countries. New England Journal of Medicine, 353 (20), 2158-2168.

Gorgos, L., & Marrazzo, J. (2011). Sexually Transmitted Infections among Women who Have Sex with Women. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 53 (S3), S84-S91.

Gustaffson, L., Pontéén, J., Zack, M., & Adami, H. (1997). International Incidence Rates of Invasive Cervical Cancer after Introduction of Cytological Screening. Cancer Causes and Control, 8 (5), 755-763.

Hildesheim, A., & Wang, S. (2002). Host and Viral Genetics and Risk of Cervical Cancer: A Review. Virus Research, 89 (2), 229-240.

Howard M., Lytwyn, A., Redwood-Campbell, L., Fowler, N., & Karwalajtys T. (2009). Barriers to Acceptance of Self-sampling for Human Papillomavirus across Ethnolinguistic Groups of Women. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 100 (5), 365-369. Howard, M., Sellors, J., Kaczorowski, J., & Lörincz, A. (2004). Optimal Cutoff of the Hybrid Capture II Human Papillomavirus Test for Self-Collected Vaginal, Vulvular, and Urine Specimens in a Coloposcopy Referral Population. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease, 8 (1), 33-37.

Joura, E., Kjaer, S., Wheeler, C., Sigurdsson, K., Iversen, O., Hernandez-Avila, M., Perez, G., Brown, D., Koutsky, L., Tay, E., Garc í a, P., Ault, K., Garland, S., Leodolter, S., Olsson, S., Tang, G., Ferris, D., Paavonen, J., Lehtinen, M., Steben, M., Bosch, X., Dillner, J., Kurman, R., Majewski, S., Muñoz, N., Myers, E., Villa, L., Taddeo, F., Roberts, C., Tadesse, A., Bryan, J., Lupinacci, L., Giacoletti, K., Lu, S., Vuocolo, S., Hesley, T., Haupt, R., & Barr, E. (2008). HPV Antibody Levels and Clinical Efficacy Following Administration of a Prophylactic Quadrivalent HPV Vaccine. Vaccine, 26 (52), 6844-6851.

Kuo, H., & Fujise, K. (2011). Human Papillomavirus and Cardiovascular Disease Among U.S. Women in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003 to 2006. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 58 (19), 2001-2006. Liguri, G., & Trisolini, F. (2010). High Sensitivity Nanotechnology-Based Multiplexed Bioassay Method and Device. United States Patent Application 0240147-A1. September 23.

Markowitz, L., Sternberg, M., Dunne, E., McQuillan, G., & Unger, E. (2009). Seroprevalence of Human Papillomavirus Types 6, 11, 16, and 18 in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2004. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 205 (7), 1059-1067.

Mayr, N., Small, W., & Gaffney, D. (2011). Cervical Cancer. In Lu, J., & Brady, L. (Eds.), Decision Making in Radiation Oncology, pp. 661-710. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Melnikow, J., McGahan, C., Sawaya, G., Ehlen, T., & Coldman, A. (2009). Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia Outcomes After Treatment: Long-term Follow-up From the British Columbia Cohort Study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 101 (10), 721-728.

Merck & Company. (2012). GARDASIL Full Prescribing Information. Whitehouse Station, New Jersey: Merck & Company. PDF.

Mitchell S., Ogilvie, G., Steinberg, M., Sekikubo, M., Biryabarema, C., & Money, D. (2011). Assessing Women's Willingness to Collect their Own Cervical Samples for HPV Testing as Part of the ASPIRE Cervical Cancer Screening Project in Uganda. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 114 (2), 111-115.

Muhlstein, J. (2011). Chronic Infection and Coronary Atherosclerosis: Will the Hypothesis Ever Really Pan Out? Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 58 (19), 2007-2009.

Muñoz, N., Castellsagué, X., De González, A., & Gissmann, L. (2006). Chapter 1: HPV in the Etiology of Human Cancer. Vaccine, 24 (S3), S1-S10.

Muñoz, N., Bosch, X., De Sanjosé, S., Herrero, R., Castellsagué, X., Shah, K., Snijders, P., & Meijer, C. (2003). Eipdemiologic Classification of Human Papillomavirus Types Associated with Cervical Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 348 (6), 518-527.

Nantunen, K., Lehtinen, J., Namujju, P., Sellors, J., & Lehtinen, M. (2011). Aspects of Prophylactic Vaccination against Cervical Cancer and Other Human Papillomavirus-Related Cancers in Developing Countries. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Article ID 675858.

Palefsky J. (2008) Human Papillomavirus and Anaöl Neoplasia. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 5 (2), 78-85.

Palefsky, J., Fillison, M., & Strickler, H. (2006). Chapter 16: HPV Vaccines in Immunocompromised Women and men. Vaccine, 24 (S3), S140-S146.

Parkin, D. (2011). Cancers Attributable to Exposure to Hormones in the UK in 2010. British Journal of Cancer, 105 (S2), S42-S48.

Parkin, D., & Bray, F. (2006). Chapter 2: The Burden of HPV-Related Cancers. Vaccine, 24 (3), S11-S25.

Petry, K., Scheffel, D., Bode, U., Gabrysiak, T., Köchel, H., Kupsch, E., Glaubitz, M., Niesert, S., Kühnle, H., & Schedel, I. (1994). Cellular Immunodeficiency Enhances the Progression of Human Papillomavirus-Associated Cervical Lesions. International Journal of Cancer, 57 (6), 836-840.

Schiffman, M., & Adrianza, M. (2000). Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance (ASCUS) - Low-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (LSIL) Triage Study: Design, Methods, and Characteristics of Trial Participants. Acta Cytologica, 44 (5), 726-742.

Shoveller, J. A., Knight, R., Johnson, J., Oliffe, J. L. & Goldenberg S. (2010). 'Not the swab!' Young men's experiences with STI testing. Sociology of Health & Illness, 32 (1), 57–73.

Smith, J., Green, J., De Gonzalez, A., Appleby, P., Peto, J., Plummer, M., Franceschi, S., & Beral, V. (2003). Cervical Cancer and Use of Hormonal Contraceptives: A Systematic Review. The Lancet, 361 (9364), 1159-1167.

Strickler, H., Palefsky, J., Shah, K., Anastos, K., Kelin, R., Minkoff, H., Duerr, A., Massad, L., Celentano, D., Hall, C., Fazzari, M., Su-Uvin, S., Bacon, M., Schuman, P., Levine, A., Durante, A., Gange, S., Melnick, S., & Burk, R. (2003). Human Papillomavirus Type 16 and Immune Status in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Seropositive Women. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 95 (14), 1062-1071.

Tóth, A., Bánky, D., & Grolmusz, V. (2012). Mathematical Modeling and Computer Simulation of Brownian Motion and Hybridization of Nanoparticle-Bioprobe-Polymer Complexes in the Low Concentration Limit. Molecular Simulation, 38 (1), 66-71.

Tóth, A., Bánky, D., & Grolmusz, V. (2011). 3D Brownian Motion Simulator for High-Sensitivity Nano-Biotechnological Applications. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Transactions of Nanobioscience, 10 (4), 248-249.

Tóth, A., Bánky, D., & Grolmusz, V. (2010). Mathematical Modeling and Computer Simulation of Brownian Motion and Hybridization of Nanoparticle-Bioprobe-Polymer Complexes in the Low Concentration Limit. Nanotech, 3, 161-164.

Trottier, H., & Burchell, A. (2009). Epidemiology of Mucosal Human Papillomavirus Infection and Associated Diseases. Public Health Genomics, 12 (5-6), 291-307.

Trisolini, F., Liguri, G., Fallani, M., & Baglini, R. (2008a). NANO-MUBIOP: About the Project..

Trisolini, F., Liguri, G., Fallani, M., & Baglini, R. (2008b). NANO-MUBIOP: HPV in the Developing Countries.

Trisolini, F., Liguri, G., Fallani, M., & Baglini, R. (2008c). NANO-MUBIOP: Expected Outcomes.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2011). Screening is Still the "Best Buy" for Tackling Cervical Cancer. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 89 (9), 621-700.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2010). International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Handbook of Cancer Prevention, Volume 10: Cervix Cancer Screening. Geneva: IARC.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2009a). Human Papillomavirus Vaccines: WHO Position Paper. Weekly Epidemiological Record, 15 (84), 117-132.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2009b). Death and Disability-Adjusted Life Year (DALY) Estimates by Cause for WHO Member States—Persons, All Ages. Geneva: WHO. XLS

World Health Organization (WHO). (2008a). Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine Background Paper. Canberra: Biotext Proprietary Company, Limited.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2008b). Cervical Cancer, Human Papillomavirus (HPV), and HPV Vaccines: Key points for Policy-Makers and Health Professionals. Geneva: WHO. World Health Organization (WHO). (2006). Comprehensive Cervical Cancer Control: A Guide to Essential Practice. Geneva: WHO.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2002a). Cervical Cancer Screening in Developing Countries. Geneva: WHO Programme on Cancer Control, Department of Reproductive Health and Research.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2002b). Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking: Summary of Data Reported and Evaluation. Geneva: WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC).

Waller, J., McCaffery, K., Forrest, S., & Wardle, J. (2004). Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer: Issues for Biobehavioral and Psychosocial Research. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 27 (1), 68-79.

Wright, T., Denny, L., Kuhn, L., Pollack, A., & Lorincz, A. (2000). HPV DNA Testing of Self-Collected Vaginal Samples Compared with Cytologic Screening to Detect Cervical Cancer. Journal of the American Medical Association, 283 (1), 81-86.

The Gendered Innovations project was asked by the European Commission to analyze several of its Framework Programme 7 (FP7) projects. "Enhanced Sensitivity Nanotechnology-Based Multiplexed Bioassay Platform for Diagnostic Applications" (NANO-MUBIOP) seeks to develop a low-cost HPV screening test. We identify gendered innovations, methods of sex and gender analysis, and points of potential "value added" through the future application of gendered innovations methods.

Gendered Innovation:

Approximately 40 types of HPV are known to infect the genital tract. HPV infection causes an estimated 100% of cervical cancer cases, and contributes to the incidence of other cancers affecting men specifically (penile cancer), women (vulvar cancer), and both women and men (anal cancer and several types of oral cancers).

NANO-MUBIOP is working to develop an inexpensive HPV test. HPV tests exist, but high cost and complexity have limited adoption.

Potential Value Added to Future Research through the Future Application of Gendered Innovations Methods:

NANO-MUBIOP seeks to develop an HPV screening platform that can be used in developing countries. Understanding the needs of this user group may require Intersectional approaches and Rethinking Research Priorities and Outcomes. An estimated 83% of HPV-attributable cancers occur in the developing world. In designing new diagnostic technology, the NANO-MUBIOP project is prioritizing characteristics that would encourage adoption in diverse low-resource areas, such as Latin America and the Caribbean, sub-Saharan Africa, Melanesia, and South-Central and South-East Asia.