What is Gendered Innovations?

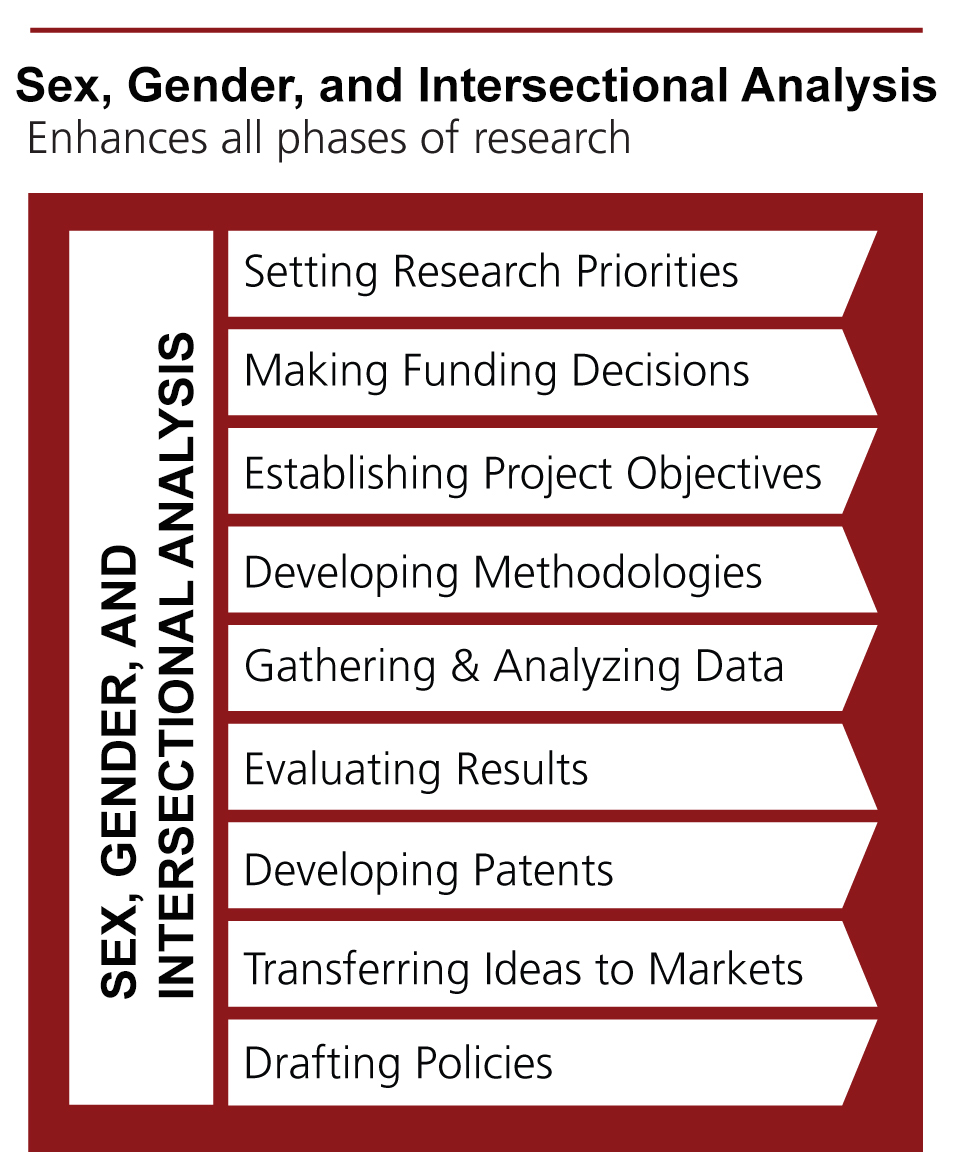

Gendered Innovations harness the creative power of sex, gender, and intersectional analysis for innovation and discovery. Considering these approaches may add valuable dimensions to research. They may take research in new directions. For a summary, see Sex and Gender Analysis Improves Science and Engineering (Nature, 2019). See also Gendered Innovations 2: How Inclusive Analysis Contributes to Research and Innovation.

The peer-reviewed Gendered Innovations project:

1) develops practical methods of sex, gender, and intersectional analysis for scientists and engineers;

2) provides case studies as concrete illustrations of how sex, gender and intersectional analysis leads to innovation.

Londa Schiebinger discusses the project in the video clip below:

Why Gendered Innovations?

Doing research wrong costs lives and money. For example, between 1997 and 2000, 10 drugs were withdrawn from the U.S. market because of life-threatening health effects. Eight of these posed "greater health risks for women than for men" (U.S. GAO, 2001). Not only does developing a drug in the current market cost billions—but when drugs failed, they caused human suffering and death.

Gender bias also leads to missed market opportunities. In engineering, for example, considering short people (many women, but also many men) “out-of-position” drivers leads to greater injury in automobile accidents (see Inclusive Crash Test Dummies). In computer vision, facial recognition trained on biased datasets may not recognize women as well as men or darker skinned persons as well as those with lighter skin, meaning that darker skinned women may not be recognized at all (see Facial Recognition). Facial recognition may also not be able to recognize transgender individuals, especially during periods of transition. In basic research, failing to use appropriate samples of male and female cells, tissues, and animals yields faulty results (see Stem Cells). In medicine, not recognizing osteoporosis as a male disease delays diagnosis and treatment in men (see Osteoporosis Research in Men). In city planning, not collecting data on caregiving work leads to inefficient transportation systems (see Smart Mobility). We can't afford to get the research wrong.

Doing research right can save lives and money. It is crucially important to identify bias. But analysis cannot stop there: Gendered Innovations offer state-of-the-art methods of sex, gender, and intersectional gender analysis. Integrating these methods into basic and applied research produces excellence in science, health & medicine, and engineering research, policy, and practice. The methods of sex, gender, and intersectional analysis are one set of methods among many that a researcher will bring to a project.

Three Strategic Approaches

Governments and universities have taken three strategic approaches to gender equality over the past several decades:- 1. "Fix the Numbers" focuses on increasing women's and underrepresented groups' participation.

- 2. "Fix the Institutions" promotes inclusive equality in careers through structural change in research organizations (NSF; European Commission, 2011).

- 3. "Fix the Knowledge" or "gendered innovations" stimulates excellence in science and technology by integrating sex, gender, and intersectional analysis into research.

Gendered Innovations:

Gendered Innovations:

● Add value to research and engineering by ensuring excellence and quality in outcomes and enhancing sustainability.

● Add value to society by making research more responsive to social needs.

● Add value to business by developing new ideas, patents, and technology.

Project Background

Gendered Innovations was initiated at Stanford University, July 2009. From 2011-2013, the European Commission funded an Expert Group, “Innovation through Gender/Gendered Innovations” under their Framework Programme 7, aimed at developing the gender dimension in EU research and innovation. The U.S. National Science Foundation joined the project January 2012. From 2018-2020, the Horizon 2020 Expert Group, Gendered Innovations (G12), updated and expanded the Gendered Innovations methods and case studies. From 2019-2022, the U.S. NSF co-funded workshops to produce new GI case studies.

To match the global reach of science and technology, the case studies and methods of sex, gender, and intersectional analysis were developed through international collaborations. More than 225 experts from across Europe, the United States, Canada, and Asia participated in a series of peer-reviewed, interdisciplinary workshops and collaborations (see Contributors). For each case study, I and my co-directors constitute a panel of experts for that specific topic and set of methods. The first of our initial interdisciplinary workshops took place across Europe and the U.S.. These were organized by co-director Marcia Stefanick and myself at Stanford, February 2011; by co-director Martina Schraudner in Berlin, March 2011; by co-director Ineke Klinge in Maastricht, June 2011; by Caroline Bélan-Ménagier, Policy Officer, Gender & Europe, French Ministry for Higher Education, Research, and Innovations, in Paris, March 2012; by co-director Inés Sánchez de Madariaga in Madrid, May 2012; by Sarah Richardson,at Harvard University, at Harvard, July 2012; and by Viviane Willis-Mazzichi, Head of Sector “Gender”, Directorate-General for Research & Innovation, EC, in Brussels, September 2012. Each workshop hosted some 15 experts, who completed and reviewed our materials. To ensure quality, everything on the Gendered Innovations website is peer reviewed. This inaugural round of Gendered Innovations also culminated in the publication of Gendered Innovations: How Gender Analysis Contributes to Research (Schiebinger & Klinge, 2013).

In 2018, I fielded a workshop at Stanford with my, then, new colleague, James Zou on gender in machine learning. We invited computer scientists from across Stanford, Google, and Facebook along with gender experts in the field. The results were published on the website (Machine Learning) and as “AI can be Sexist and Racist — It’s Time to Make it Fair” in Nature (Zou & Schiebinger, 2018). I also held a workshop on gender in robotics with marvelous roboticists, mostly from the West Coast, where we developed the popular case study, Gendering Social Robots.

In late 2018, Gendered Innovations received funding again from the European Commission to develop what we called Gendered Innovations 2. This group consisted of 29 experts—from systems biology to drug development to civil engineering, among other fields. I also recruited a new generation of co-directors, Elena Gissi, Senior Scientist at the Institute of Marine Sciences in Venice, Mathias W. Nielsen, Professor of Sociology, Copenhagen University, and Sabine Oertelt-Prigione, Professor of Sex- and Gender-Sensitive Medicine at Radboud University in the Netherlands and Bielefeld University in Germany. Each was instrumental in bringing new skills and materials to Gendered Innovations. Anne Pépin, Senior Policy Officer, Gender Sector of the EC’s Directorate General for Research and Innovation, convened the expert group that met in three in-person workshops in Brussels and developed some fifteen new case studies, ranging from analyzing sex in marine science—something completely new—to analyzing gender in smart energy solutions and quality urban spaces. Methodologically, Gendered Innovations 2 updated numerous case studies to mainstream intersectionality. In addition to our “general methods,” we added “field specific methods,” for health & biomedicine, machine learning, and marine science. The new project, Gendered Innovations 2: How Inclusive Analysis Contributes to Research and Innovation, was ready to go March 2020, but the launch was delayed until November by the dangers and devastation of COVID-19 (Schiebinger & Klinge, 2020).

Meanwhile, the U.S. NSF and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) initiated a collaboration to highlight intersectionality in science and engineering. Stephanie Adams, Dean and Lars Magnus Ericsson Chair at the University of Texas at Dallas, our Canadian collaborators, and I organized two workshops on Inclusive and Intersectional Research and Analysis in Engineering and Computer Science, the first in 2020 in Washington, D.C., and the second scheduled for February 2021 in Ottawa—which became virtual because of COVID-19. These workshops resulted in the development NSERC’s guide on Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Considerations at Each Stage of the Research Process, designed to support Canada’s forward-looking policies on integrating sex, gender, and intersectional analysis into research design. NSF to date has not developed policy specifically on this issue, which in my view is a missed opportunity.

With money not spent because of COVID, Stephanie and I were able to host a third workshop at Stanford in late 2022. This led to the develop of three new case studies: on computer science curriculum that addressed the issue of responsible computing and how intersectional approaches might be integrated into core engineering and computer science courses (Computer Science Curriculum), domestic robots that looked at the gender and intersectional issues that arise when bringing robots into the home (Domestic Robots), and green technologies focused on sustainable fashion (Sustainable Fashion), where we developed new insights from the intersection of environment and social life cycle assessments.

As we look toward the future, Gendered Innovations is moving increasingly into sustainability, where we seek to cultivate two interrelated social goods: social equality and environmental sustainability.

Collaborations

Gendered Innovations collaborated in the development of the 2010 genSET Consensus Report and the United Nations Resolutions related to Gender, Science and Technology passed March 2011.

July 9, 2013 the Gendered Innovations project was presented at the European Parliament. As part of that session, we published Gendered Innovations: How Gender Analysis Contributes to Research with a foreword by European Commissioner Máire Geoghegan-Quinn. European Union policy prioritizes "the gender dimension in research and innovation content." August 2015, Gendered Innovations was the theme of the Gender Summit 6 Asia-Pacific, Seoul, South Korea. In September 2015, the League of European Research Universities released Gendered Research and Innovation. In 2020, the European Commission expert group work was published as: Gendered Innovations 2: How Inclusive Analysis Contributes to Research and Innovation, eds. Londa Schiebinger and Ineke Klinge (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union) with a foreword by European Commissioner for Innovation, Research, Culture, Education and Youth, Mariya Gabriel. In 2016, the Center for Gendered Innovations in Science and Technology Research was founded in Seoul, Republic of Korea. In 2022, the Institute for Gendered Innovation was created at Ochanomizu University, Tokyo, Japan.Sex and Gender Analysis Lead to Gendered Innovations:

|

|

|

||

|

||||

|

|

|

||

|

||||

|

|

|

||

|

||||

|

|

|

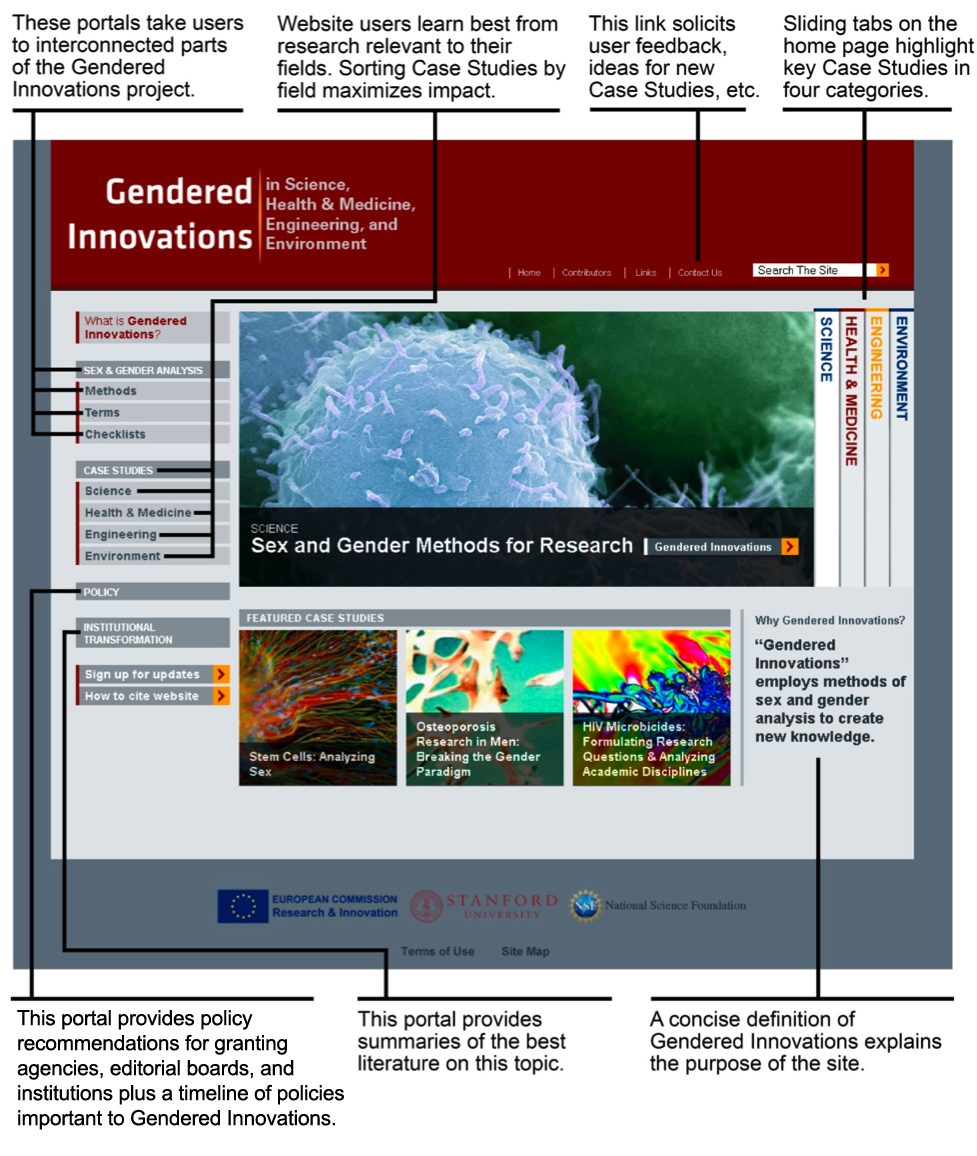

How to Use this Website:

This website has five interactive main portals:

1. Methods of sex, gender and intersectional analysis for research and engineering

2. Case studies illustrate how sex, gender, and intersectional analyses leads to innovation

3. Terms address key concepts used throughout the site

4. Checklists for researchers and evaluators

5. Policy provides recommendations in addition to links to key national and international policies that support Gendered Innovations

The term "Gendered Innovations" was coined by Londa Schiebinger in 2005.

© European Union, 2011, 2020© Stanford University, 2011

Works Cited

European Commission. (2011). Structural Change in Research Institutions: Enhancing Excellence, Gender Equality, and Efficiency in Research and Innovation. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

National Science Foundation (NSF). ADVANCE Adaptation and Partnership Proposals in Solicitation NSF 20-554. "NSF ADVANCE proposals are expected to use intersectional approaches in the design of systemic change strategies in recognition that gender, race and ethnicity do not exist in isolation from each other and from other categories of social identity." Accessed 20 November 2020.

Schiebinger, L. & Klinge, I. Eds. (2020). Gendered Innovations 2: How Inclusive Analysis Contributes to Research and Innovation (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020). Foreword by EC Commissioner for Innovation, Research, Culture, Education and Youth, Mariya Gabriel.

Tannenbaum, C., Ellis, R. P., Eyssel, F., Zou, J., & Schiebinger, L. (2019). Sex and Gender Analysis Improves Science and Engineering. Nature, 575(7781), 137-146.

United States General Accounting Office. (2001). Drug Safety: Most Drugs withdrawn in Recent Years had Greater Health Risks for Women. Washington, DC: Government Publishing Office.