Sex, Gender, & Intersectional Analysis

Case Studies

- Science

- Health & Medicine

- Chronic Pain

- Colorectal Cancer

- Covid-19

- De-Gendering the Knee

- Dietary Assessment Method

- Gendered-Related Variables

- Heart Disease in Diverse Populations

- Medical Technology

- Nanomedicine

- Nanotechnology-Based Screening for HPV

- Nutrigenomics

- Osteoporosis Research in Men

- Prescription Drugs

- Systems Biology

- Engineering

- Assistive Technologies for the Elderly

- Domestic Robots

- Extended Virtual Reality

- Facial Recognition

- Gendering Social Robots

- Haptic Technology

- HIV Microbicides

- Inclusive Crash Test Dummies

- Human Thorax Model

- Machine Learning

- Machine Translation

- Making Machines Talk

- Video Games

- Virtual Assistants and Chatbots

- Environment

Textbooks: Rethinking Language and Visual Representations

The Challenge

Textbooks carry core knowledge to students in science and engineering. Further, textbooks shape impressions of the nature of scientific work—impressions of who becomes a scientist or of what kinds of problems engineers work to solve. Textbooks that embed stereotypes of sex and gender in materials perpetuate gender assumptions and produce unsound science.

Method: Rethinking Language and Visual Representations

Language (word choice, metaphors, analogies, and naming practices chosen to explain scientific concepts) and visual representations (images, tables, and graphs chosen to illustrate scientific concepts) have the power to shape scientific practice, the questions asked, the results obtained, and the interpretations made. Rethinking language and visual representation in textbooks can help remove unconscious gender assumptions that restrict discovery and innovation, and thereby reduce gender inequalities.

Gendered Innovations:

1. Revising biology textbooks to incorporate new findings from sex and gender research. In developmental biology, this includes expanding accounts of human fertilization to reflect the active role played by the female reproductive system in sperm transportation and capacitation. In bacteriology, this includes removing scientifically unsound metaphors that present bacteria as sexed organisms.

2. Revising physics textbooks to illustrate scientific principles through more gender neutral examples.

Gendered Innovation 1: Revising Biology Textbooks

Example A: Developmental Biology

Method: Rethinking Concepts and Theories

Example B: Bacteriology

Gendered Innovation 2: Revising Physics Textbooks

Method: Rethinking Language and Visual Representation

Conclusion and Next Steps

The Challenge

Textbooks present working assumptions within the field of science at the time of their publication. Information in textbooks also forms the knowledge base for the next generation of scientists.

Gendered Innovation 1: Revising Biology Textbooks

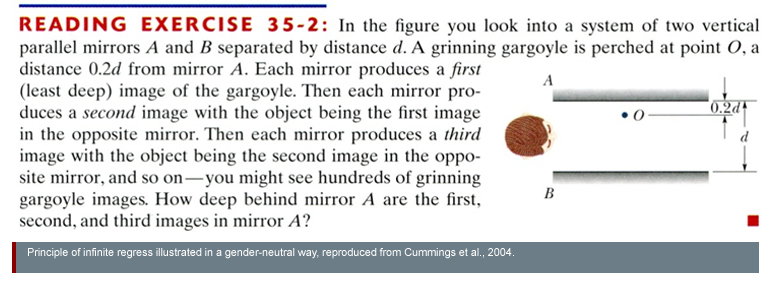

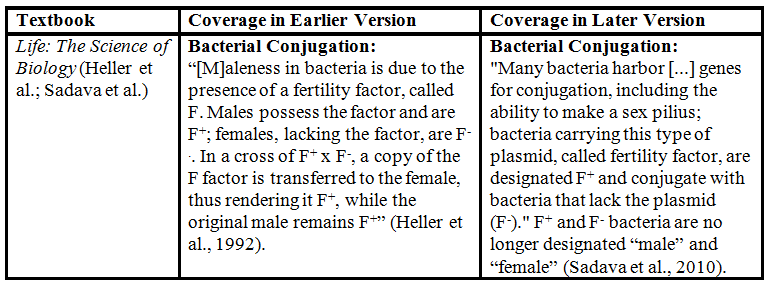

Biology textbooks have undergone major revisions to incorporate new findings from sex and gender research. In developmental biology, the science presented in textbooks has changed as authors add more information about the role of the female reproductive tract in transporting and combining gametes in fertilization. In bacteriology, the metaphors used in textbooks have changed as authors avoid assigning sex to bacteria.

Example A: Developmental Biology:

In the 1980s, textbooks still included accounts of human conception that featured an "active" sperm capturing a "passive" egg (Martin, 1992). Textbooks emphasized the self-propelled nature of sperm without attention to the roles that the female reproductive system plays in transporting both egg and sperm. Similarly, textbooks described the role of the sperm in activating egg development without significant discussion of the female reproductive tract in activating sperm (Alberts et al., 1983).

Current textbooks have been rewritten to include new findings about the active role of the female reproductive system in transporting sperm and in preparing ("capacitating") sperm for conception. The table below shows changes in two major biology textbooks:

These changes resulted from rethinking gender concepts and theories, and have improved both the scientific accuracy and the gender neutrality of textbooks (see Method).

Method: Rethinking Concepts and Theories

Challenging unconscious gender assumptions in basic scientific concepts, such as the "active" male and "passive" female, has changed what is included in textbooks and can enhance scientific research itself. Textbook authors who understand the active role of both the female and male in conception provide more comprehensive information about developmental biology. The female reproductive tract has been known to transport sperm since the 1930s, when experiments in several model species demonstrated that "the passage of sperm into and through the uterus of various animals [...] is due to activities other than their own motility" (Krehbiel et al., 1939). The inclusion of this information in textbooks, however, is recent.

Training researchers to challenge unconscious gender bias in basic scientific concepts can also bring to light new evidence, including the active role the female reproductive system plays in transporting sperm towards a particular ovary. During the late follicular phase, immediately before ovulation, the uterus and fallopian tubes of a woman will actively transport sperm towards the dominant follicle. This "guarantees a maximum number of spermatozoa at the site of fertilization," as "a fertilizable oocyte is released from only one ovary during the normal cycle." This process may be controlled by thermal and hormone concentration gradients (Zervokanolakis et al., 2009).

The choice to employ this metaphor of the “passive” female is not inconsequential. Rather, as scholars have shown scientific metaphors are “ideologically loaded” (Navare, 2023). For instance, Charudatta Navare has argued that one reason textbooks tend to describe the “nucleus as the control center” of the cell is not due to a scientific reality, but rather related to the concept’s consistency with pervading gender ideologies that mark the nucleus as male and the cytoplasm as female (Navare, 2023; Keller, 1997). Further, as Navare shows, these metaphors also encode and naturalize different racial and class structures (Navare, 2023).

Key questions for this method are: How do notions of sex or gender influence how research is conducted in a particular field—i.e., the choice of research topics, methodologies, what counts as evidence, and how it is interpreted? How do these concept and theories contribute to formulating research questions?

Example B: Bacteriology:

Bacterial conjugation is a non-reproductive process by which bacteria can send and receive genetic material (Lederberg et al., 1946). Conjugation differs from sexual reproduction in numerous and important ways (see Method below). In 1992, however, a textbook utilized sex as a metaphor to describe bacterial conjugation—designating donor-type bacteria carrying the fertility plasmid (F+) as "male" and recipient-type bacteria not carrying the plasmid (F-) as "female." In addition to being inaccurate, this metaphor equates "information-sending" with maleness and "information-receiving" with femaleness (Spanier, 1995). Textbook authors are now avoiding such metaphors; see table for changes.

These changes are a result of authors rethinking the language—and the cultural messages embedded in a particular metaphor—to describe bacterial conjugation (see Method below).

Gendered Innovation 2: Revising Physics Textbooks

Current physics textbooks strive to illustrate scientific principles in gender neutral ways—that is, in ways which avoid presenting scientific activities as more "gender-appropriate" for men than for women, for example.

Current physics textbooks strive to illustrate scientific principles in gender neutral ways—that is, in ways which avoid presenting scientific activities as more "gender-appropriate" for men than for women, for example.

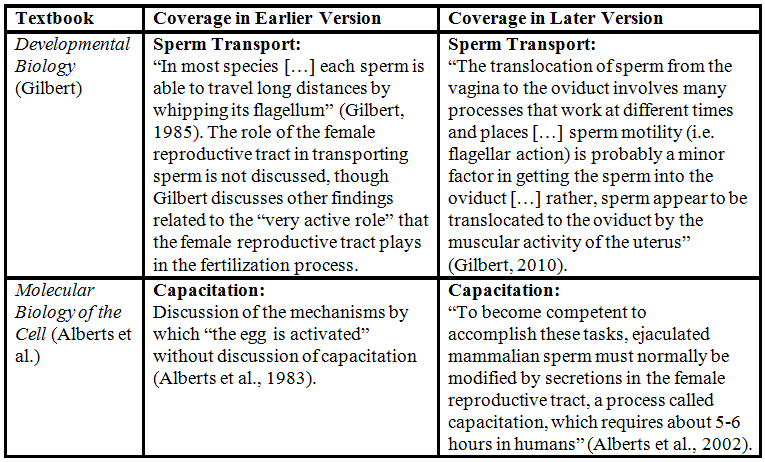

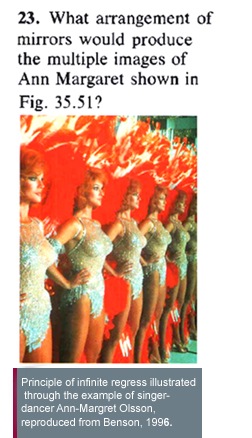

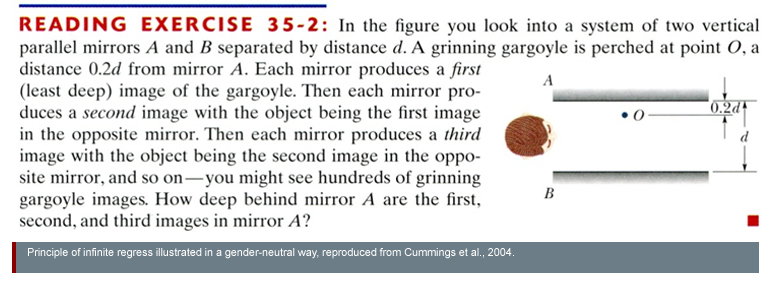

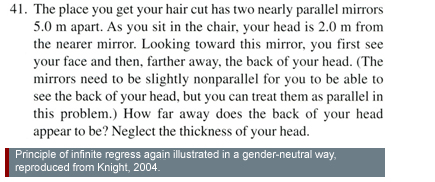

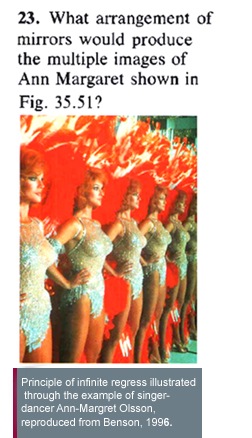

Example: University level physics textbooks include sections dedicated to ray optics, with emphasis on mathematical models of mirrors, lenses, prisms, and other optical elements. One phenomenon explained is "infinite regress," or the use of parallel plane mirrors to produce an infinite series of ever-smaller reflections.

Benson's University Physics: Revised Edition illustrates infinite regress with a photograph of Ann-Margret Olsson standing between two plane mirrors in cabaret attire, as shown at left (Benson, 1996). This illustration is problematic in several ways. The image unnecessarily presents Olsson in revealing clothing; nothing in the science being explained requires such an image. This image may offend potential physics students, especially women; surveys indicate that women have on average more negative views of commercial sexually-explicit imagery than do men (Häggström-Nordin et al., 2009). It may also disproportionately offend students from sexually conservative cultures; there are significant geographic and generational differences in viewer's attitudes towards sexually-charged images (Fam et al., 2008).

Other textbooks present the same concept without utilizing such images. For example, Cummings et al.'s Understanding Physics uses a presumably gender-neutral example of a gargoyle situated between two mirrors, as shown below (Cummings et al., 1996).

Another textbook, Knight's Physics for Scientists and Engineers, does not include any image or diagram but instead references a situation (again presumably gender neutral) in which one is likely to have experienced the phenomenon first hand, as shown at left (Knight, 2004, pp. 753).

Another textbook, Knight's Physics for Scientists and Engineers, does not include any image or diagram but instead references a situation (again presumably gender neutral) in which one is likely to have experienced the phenomenon first hand, as shown at left (Knight, 2004, pp. 753).

Method: Rethinking Language and Visual Representations

Word choice, charts, graphs, metaphors, and images have the power to shape scientific practice and reinforce beliefs about gender roles. Words and images selected to illustrate scientific principles in textbooks may influence: who participates in science, how research priorities are set, and how scientific findings are interpreted. Metaphors employed to explain particular scientific concepts implicitly convey ideological and cultural norms. This is particularly true for textbooks, which are legitimized as “official knowledge” within society (Apple 1990; Navare, 2023). Fundamental concepts in any field should not be taken for granted; they should be critically analyzed for gender and other assumptions. Challenging unconscious gender bias helps to ensure rigor in generating and testing hypotheses and conveying knowledge to students.

Language and images used in textbooks can influence students by:

- 1. Reinforcing stereotypes about gender roles. In the case of developmental biology, omitting information about the role of the female reproductive tract in sperm transport and capacitation may reinforce cultural stereotypes that portray females as passive. In the case of bacterial conjugation, designating F+ individuals as "male" and F- individuals as "female" associates maleness with active information donating and femaleness with passive information receiving.

- 2. Leading to unintended hypotheses or incorrect results. In the case of bacterial conjugation discussed above, assigning sex to bacteria misrepresents conjugation in several ways, including:

- A. Assigning sex to individuals of a species implies that the species reproduces sexually; however, bacterial conjugation is not a reproductive process.

- B. Bacterial conjugation can transform F- individuals into F+ individuals; in sexually-reproducing species, the sex of an individual is generally fixed and is not transformed through contact with other individuals. Defining F- and F+ as "female" and "male" implies that conjugation transforms females to males; sexual reproduction does not normally have this result (Spanier, 1995).

- C. Bacterial conjugation can occur between individuals of different species, while sexual reproduction occurs only within a species (Tsinoremas et al., 1994). Interspecies conjugation has important medical implications, because it can allow bacteria to accumulate genes which confer antibiotic resistance (Griffiths et al., 2000).

- 3. Disproportionately recruiting women or men to a given field. In the physics example above, the way scientific principles are illustrated can send unintended cultural messages about who should participate in the field. This may lead to disparities in scientific education and later employment (Tindall et al., 2004).

Conclusions and Next Steps

Textbooks are used to educate the next generation of scientists and engineers, and should be checked for unintended gender assumptions. Rethinking language and visual representations can:

- Remove assumptions that may limit or restrict innovation and knowledge in unconscious ways.

- Remove assumptions that unconsciously reinforce inequalities.

Works Cited

Alberts, B., Johnson, A., Lewis, J., Raff, M., Roberts, K., & Walter, P. (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science.

Alberts, B., Bray, D., Lewis, J., Raff, M., Roberts, K., & Watson, J. (1983). Molecular Biology of the Cell (1st ed.). New York: Garland Science.

Apple, M. W. (1990). The Text and Cultural Politics. The Journal of Educational Thought (JET)/Revue de La Pensée Éducative, 24(3A), 17–33.

Benson, H. (1996). University Physics: Revised Edition. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Cummings, K., Laws, P., Redish, E., & Cooney, P. (2004). Understanding Physics, Part 4. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons.

Fam, K., Waller, D., Ong, F., & Yang, Z. (2008). Controversial Product Advertising in China: Perceptions of Three Generational Cohorts. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 7 (6), 461-469.

Gilbert, S. (2010). Developmental Biology (9th ed.). Sunderland: Sinauer Associates.

Gilbert, S. (1985). Developmental Biology (1st ed.). Sunderland: Sinauer Associates.

Griffiths, A., Miller, J., Suzuki, D., Lewontin, R., & Gelbart, W. (2000). An Introduction to Genetic Analysis (7th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company.

Häggström-Nordin, E., Tydén, T., Hanson, U., & Larsson, M. (2009). Experiences Of and Attitudes Towards Pornography among a Group of Swedish High School Students. European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Healthcare, 14 (4), 277-284.

Heller, H., Orians, G., & Purves, W. (1992). Life: The Science of Biology (3rd ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

Keller, E. F. (1997). Developmental Biology as a Feminist Cause? Osiris, 12(1), 16–28.

Knight, R. (2004). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: A Strategic Approach, Volume 3. San Francisco: Addison Wesley.

Krehbiel, R., & Carstens, H. (1939). Roentgen Studies of the Mechanism Involved in Sperm Transportation in the Female Rabbit. American Journal of Physiology, 125 (3), 571-578.

Lederberg, J., & Tatum, E. (1946). Gene Recombination in Escherichia Coli. Nature, 158 (4016), 558.

Martin, E. (1992). The Woman in the Body: A Cultural Analysis of Reproduction. Boston: Beacon.

Navare, C. (2023). Instructions, commands, and coercive control: A critical discourse analysis of the textbook representation of the living cell. Cultural Studies of Science Education.

Sadava, D., Hillis, D., Heller, H., & Berenbaum, M. (2010). Life: The Science of Biology (9th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman.

Spanier, B. (1995). Im/partial Science: Gender Ideology in Molecular Biology. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Tindall, T., & Hamil, B. (2004). Gender Disparity in Science Education: The Causes, Consequences, and Solutions. Education, 125 (2), 282-295.

Tsinoremas, N., Kutach, A., Strayer, C., & Golden, S. (1994). Efficient Gene Transfer in Synechococcus sp. Strains PCC 7942 and PCC 6301 by Interspecies Conjugation and Chromosomal Recombination. Journal of Bacteriology, 176 (21), 6764-6768.

Zervomanolakis, I., Ott, H., Müller, J., Seeber, B., Friess, S., Mattle, V., Virgolini, I., Heute, D., & Wildt, L. (2009). Uterine Mechanisms of Ipsilateral Directed Spermatozoa Transport: Evidence for a Contribution of the Utero-Ovarian Countercurrent System. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Supplement on Reproductive Bioengineering, 144 (1), S45-S49.

Textbooks carry core knowledge to students in science and engineering. Further, textbooks shape impressions of the nature of scientific work—about who becomes a scientist or what kinds of problems engineers work to solve. Textbooks can also embed stereotypes that perpetuate gender assumptions and produce unsound science.

Language (word choice, metaphors, analogies, and naming practices chosen to explain scientific concepts) and visual representations (images, tables, and graphs chosen to illustrate scientific concepts) have the power to shape scientific practice: the questions asked, the results obtained, and the interpretations made. Rethinking language and visual representation in textbooks can help remove unconscious gender assumptions that restrict discovery and innovation.

Gendered Innovations:

- 1. Revising biology textbooks to incorporate new findings from sex and gender research. In developmental biology, this includes expanding accounts of human fertilization to reflect the active role played by the female reproductive system in sperm transportation and capacitation. In bacteriology, this includes removing scientifically unsound metaphors that present bacteria as sexed organisms.

- 2. Revising physics textbooks to illustrate scientific principles through more gender-neutral examples.

This image might send the wrong messages about who should study to become a physicist.

The image above has been replaced by a gender-neutral image (below).