Sex, Gender, & Intersectional Analysis

Case Studies

- Science

- Health & Medicine

- Chronic Pain

- Colorectal Cancer

- Covid-19

- De-Gendering the Knee

- Dietary Assessment Method

- Gendered-Related Variables

- Heart Disease in Diverse Populations

- Medical Technology

- Nanomedicine

- Nanotechnology-Based Screening for HPV

- Nutrigenomics

- Osteoporosis Research in Men

- Prescription Drugs

- Systems Biology

- Engineering

- Assistive Technologies for the Elderly

- Domestic Robots

- Extended Virtual Reality

- Facial Recognition

- Gendering Social Robots

- Haptic Technology

- HIV Microbicides

- Inclusive Crash Test Dummies

- Human Thorax Model

- Machine Learning

- Machine Translation

- Making Machines Talk

- Video Games

- Virtual Assistants and Chatbots

- Environment

Smart Mobility: Co-Creation and Participatory Research

The Challenge

Mobility patterns tend to be gendered in terms of where, when, and why people take trips. Transportation planning—both for modes and infrastructures—often do not take into account diverse users’ needs. For example, the need for safety can restrict mobility for specific women, gender nonconforming individuals, and the elderly.

Method: Co-Creation and Participatory Research

Understanding gender-specific needs across populations of different genders, ages, religions, ethnicities, socioeconomic status, etc. can add new perspectives to the collection of transportation data and design. Participatory research enables new services to be conceptualized from the perspective of users from across broad populations. This can add new insights for: 1) relevant functionalities, i.e. what services are needed; 2) configuration of vehicles and infrastructures, i.e. vehicle features and routes; and 3) technologies used to access services.

Gendered Innovations:

1. The Mobility of Care. National Household Travel Surveys underrate trips performed as part of caring work, i.e., doing errands to meet household needs or to accompany others. Reconceptualizing data collection to include caring work as a dedicated category allows transportation engineers to design systems that work efficiently for broader segments of the population.

2. Enhancing Public Transportation. The LivingLab in Germany used participatory research to understand the needs of their riders. As a result, they introduced smaller buses with flexible routes and a dense pattern of flexible stops that allowed people to get on or off a bus close to the start or end of their journey. This made public transport more user-friendly and efficient for all users—women, men, gender-diverse people, and people from differing socioeconomic and regional backgrounds.

3. A Toolbox for Gender-Sensitive Decision Making. Developing and applying methodologies to assess gender-specific needs can improve mobility options for more passengers, and simultaneously promote environment-friendly mobility behaviors.

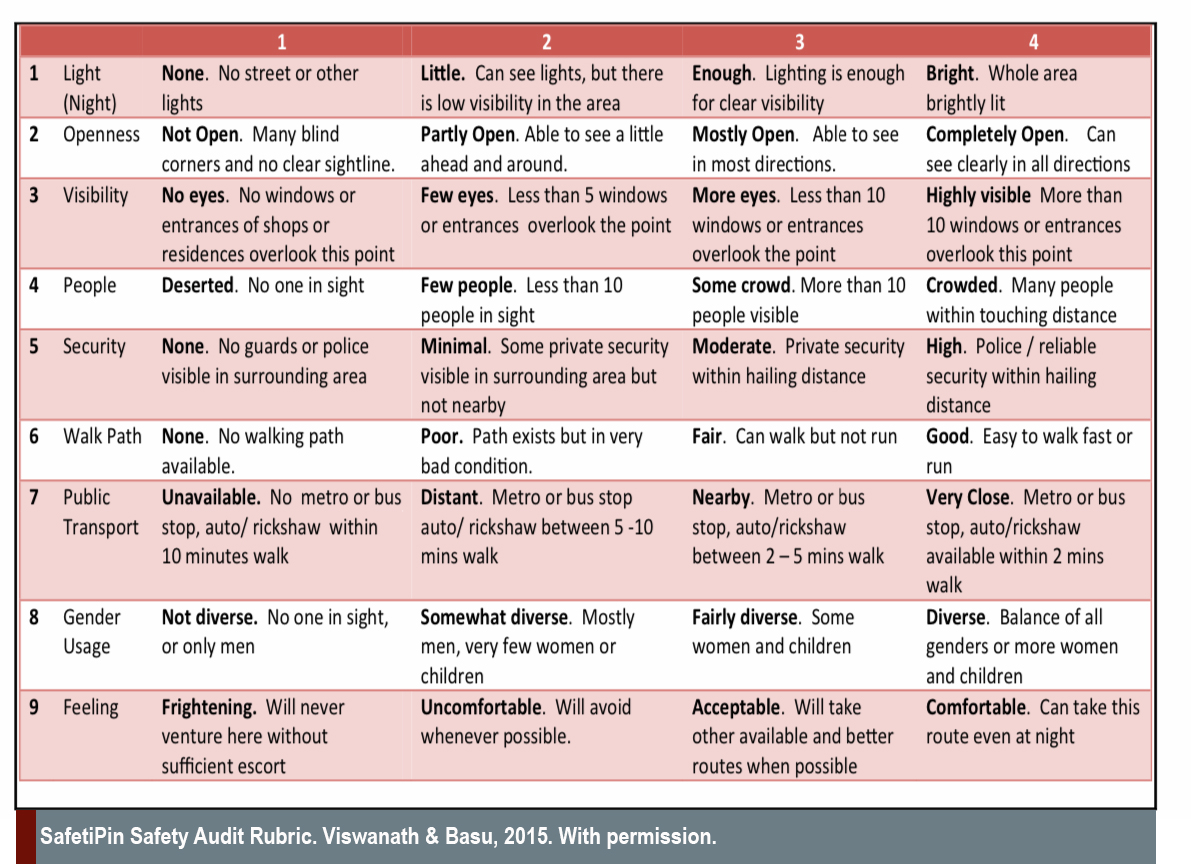

4. New Safety Features for Ride-Hailing Services. Numerous innovations surround safety concerns for women, LGBTQ+ individuals, and older people using ride-hailing services. One such innovation is SafetiPin, developed in Delhi, India, in response to the fatal gang rape of a 23-year-old woman in 2012. Using crowdsourced information and safety audits, SafetiPin calculates the safest route between two locations.

The Challenge

Mobility patterns are gendered. Typically, one can still observe gender norms, gender-specific divisions of labor in households, and gender disparities in resources. Gendered household labor is particularly important on the demand side, since trips related to caring—running the household, errands or caring for others—are different from commuting to work. Another set of issues has to do with safety. On the supply side, urban transportation is increasingly offering smart mobility options underpinned by information and communications technology (ICT) platforms designed to ease access to transportation services and to personalize modern transportation. These developments, however, have largely ignored gender (Nobis & Lenz, 2009; Nobis & Lenz, 2019; Lenz, 2020).

To close the gap between gender-specific needs and new smart mobility services, we need to: 1) understand gender-specific needs across populations of different genders, ages, religions, socioeconomic status, etc.; 2) develop and apply gender-sensitive methodologies to assess those needs and to co-create services that enhance mobility options.

Gendered Innovation 1: The Mobility of Care

Effective transportation systems rely on Big Data. Transportation planners collect data to understand how people use different modes of transport—cars, bikes, trains, subways and buses. The gendered innovation is to reconceptualize how data are collected and analyzed.

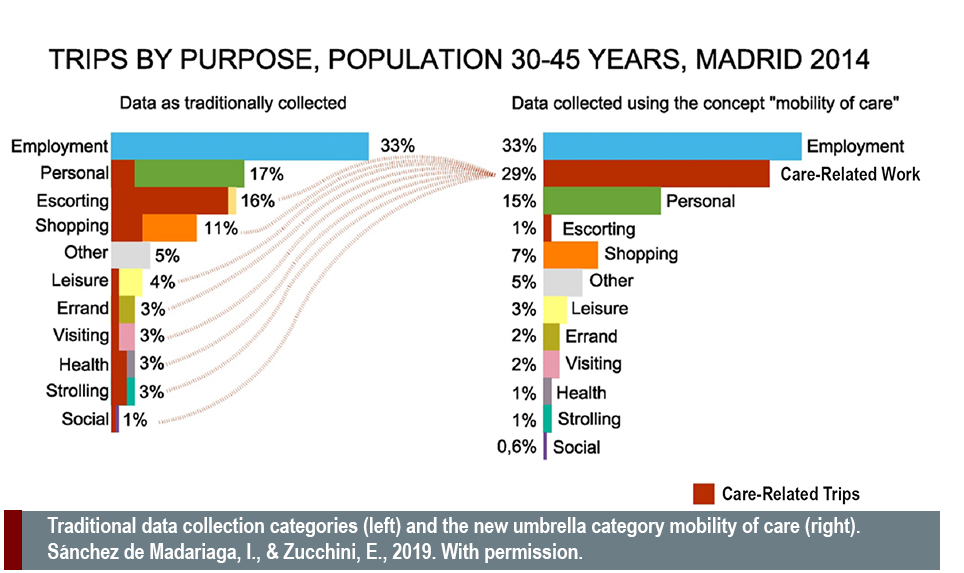

Researchers examining public transport often categorize trips by purpose to better understand existing transportation patterns and to plan infrastructure changes. Traditional categories used in transportation surveys collect information about trips for employment, education, shopping, leisure and the like (see graph below—left side). Categories used by the U.S. National Household Travel Survey (NHTS, 2017), for example, include work, school/day-care/religious activity, medical/dental services, shopping/errands, social/recreational, transport someone, meals out-of-home, home, something else. These roughly correspond to those used by most European National Travel Surveys.

The innovative concept “mobility of care” reveals significant travel patterns otherwise concealed in data collection variables (Sánchez de Madariaga, 2009, 2013). The charts below represent public transportation trips made in Madrid, Spain, in 2014. The first chart (left) graphs transportation data as traditionally collected and reported. It privileges paid employment by presenting it as a single large category. Caring work (shown in red) is divided into numerous small categories and hidden under other headings, such as escorting, shopping and leisure.

The second chart (right) reconceptualizes public transportation trips by collecting care trips into one category. Visualizing care trips in one dedicated category recognizes the importance of caring work and allows transportation engineers to design systems that work well for broader segments of the population (Sánchez de Madariaga & Zucchini, 2019).

Method: Reconceptualizing Data Collection

Reconceptualizing data collection is important because women perform a relatively large share of accompanying trips. They make more short trips and more chained trips than men (Allen and Alam, 2019). Women also tend to prefer shorter distances between home and the workplace. These observations are true in particular for households with two or more adults between the ages of 30 and 50. These differences do not apply to younger or single-person households (Nobis & Lenz, 2005).

Gendered Innovation 2: Enhancing Public Transportation

Beyond how data are collected and analyzed, it is important to develop gender-sensitive methodologies to better address the needs of public transport users.To introduce dynamic ICT-based public transport services, a “LivingLab” was set up in Schorndorf, a city in the South of Germany, to experiment with gender-sensitive methodologies (LivingLab “Reallabor Schorndorf,” 2018; Gebhardt et al., 2019). The objective was to make public transport more user-friendly and efficient. To this end, conventional public transport was transformed into an on-demand bus service at times when demand tended to be low and variable, such as evenings and weekends. The service used a digital platform with access via a smartphone app, the internet or a telephone. The LivingLab introduced smaller buses with flexible routes and a dense pattern of flexible stops that allowed people to get on or off the bus close to the start or end of their journey. Users did not have to walk to traditional designated bus stops.

This gender-sensitive on-demand service addressed the specific needs of women and contributed to the comfort of all users in need of safe and efficient off-peak services:

• Users, especially young women and girls, found the on-demand bus provided a safe way home. Longer walks from the flexible bus stop to home, sometimes leading through pedestrian subways, could be eliminated. At the same time, waiting times for the bus were considerably reduced.

• Smaller on-demand buses provided an improved feeling of safety for people travelling in the evening or at night, as all seats were close to the driver. (The need for the presence of a driver to ensure safety was a reason women argued against autonomous vehicles.) Providing mobility services that are perceived as safe enhances options for out-of-home activities, especially for elderly people who often restrict those activities to daylight hours (Giesel & Rahn, 2015).

The LivingLab included participatory research, where users contributed to concepts and evaluated designs (see below). Users emphasized a need for multi-functional spaces in the on-demand vehicle that could accommodate strollers, shopping trolleys or walking aids, required by elderly passengers in particular. A curb-to-bus ramp allowed barrier-free access to the vehicle for passengers and their equipment.

While designed with women in mind, this project has the potential to improve safety for all users—men, gender-diverse people and people from diverse socioeconomic and regional backgrounds.

Method: Co-Creation and Participatory Research

The LivingLab used co-creation and co-design, also known as participatory research, to investigate different user groups and their needs when designing the new mobility services. These methods enable new services to be conceptualized from customer perspectives and include a gender-sensitive framework. This method added new insights to: 1) the relevant functionalities, i.e. what services are needed; 2) the configuration of vehicles and infrastructures, i.e. vehicle features and routes; and 3) relevant ICT access to the service.

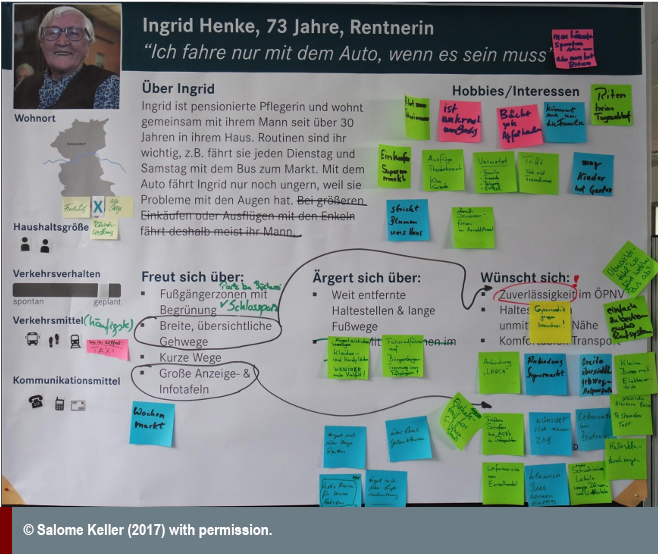

To apply this participatory research within the LivingLab, “typical representatives” (similar to “personas”) of the overall population were developed to stimulate discussion in those involved in the co-design workshops (Baumann, 2010; Beyer & Müller, 2019; Miaskiewicz & Kozar, 2011; Pruitt & Adlin, 2006). The goal was to understand the specific needs, contexts, and conditions of users across the broader population (not just the participants themselves) and across gender groups in particular. These “typical representatives” emerged from a survey of the population to be served. The people participating in the co-design workshops developed services (including vehicles) for these “typical representatives”. For example, the senior citizen “Ingrid Henke” represented elderly people who own a car but use it only if there is no alternative, and “Hans Lehmann” represented disabled people who depend on barrier-free public transport to get to their workplace.

To apply this participatory research within the LivingLab, “typical representatives” (similar to “personas”) of the overall population were developed to stimulate discussion in those involved in the co-design workshops (Baumann, 2010; Beyer & Müller, 2019; Miaskiewicz & Kozar, 2011; Pruitt & Adlin, 2006). The goal was to understand the specific needs, contexts, and conditions of users across the broader population (not just the participants themselves) and across gender groups in particular. These “typical representatives” emerged from a survey of the population to be served. The people participating in the co-design workshops developed services (including vehicles) for these “typical representatives”. For example, the senior citizen “Ingrid Henke” represented elderly people who own a car but use it only if there is no alternative, and “Hans Lehmann” represented disabled people who depend on barrier-free public transport to get to their workplace.

Improving and enhancing options for public transport and supplementing services may also help reduce environmental harm in cities. The German Environmental Agency (UBA) has analyzed greenhouse gas and air pollutant emissions per person-kilometer. The results indicate, for instance, that car users in Germany emit 0.004g particulate matter/person-km (given the average occupancy of 1.5 persons per car) vs. 0.000g for public transport users in cities (UBA, 2019). Enhancing the usability of public transportation helps cities and regions meet their environmental goals.

| Car | Airplane (inland) | Railway (long distance) | Coach (long distance) | Railway (local transport) | Public bus | Light rail and metro | ||

| GHG | g/pkm* | 147 | 230 | 32 | 29 | 58 | 80 | 58 |

| Carbon monoxide | g/pkm | 1.00 | 0.48 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Volatile hydrocarbons | g/pkm | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| Nitric oxide | g/pkm | 0.43 | 1.01 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.05 |

| Particulate matter | g/pkm | 0.004 | 0.011 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| Average occupation rate | 1.5 pers./car | 71% | 56% | 55% | 28% | 19% | 19% |

*gram per person-kilometer. Source: UBA, 2019.

Gendered Innovation 3: A Toolbox for Gender-Sensitive Decision Making

Gender-sensitive research combines quantitative methods such as data mining and analytics with qualitative methods such as surveys, focus groups or individual in-depth interviews aimed at understanding user needs, preferences, barriers or objections.The use of quantitative and qualitative methods is featured in the EU-funded project DIAMOND (2018-2021), which seeks to enhance fairness in transport. Fairness, here, is defined as a state in which people are treated similarly, unimpeded by prejudices or unnecessary distinctions or barriers, unless these are well-understood and justified. DIAMOND is aimed specifically at supporting gender inclusion in current and future transport systems.

Starting from specific use cases, such as vehicle sharing and automated vehicles, DIAMOND collects data that can be fed into a self-diagnostic tool (Decision Support System) that can be used by transportation system engineers to understand individual user characteristics such as gender, age, ethnicity, religion, family, disability, socioeconomic status, etc. Designers can then develop fairness measures. For vehicle sharing, for example, knowing what percentage of shared vehicles are used by elderly women, young men, gender-diverse individuals or persons in need of physical assistance helps planners make gender-sensitive decisions about fleet distribution across geographic locations.

Gendered Innovation 4: New Safety Features for Ride Hailing

Numerous innovations surround safety concerns for women, LGBTQ+ individuals, and older people using ride-hailing services. One such innovation is SafetiPin, developed in Delhi, India, in response to the fatal gang rape of a 23-year-old woman in 2012. Using crowdsourced information and safety audits, SafetiPin calculates the safest route between two locations. Safety information can also be shared with city authorities; Delhi, for example, improved lighting in over 5,000 locations in response to user data. SafetiPin now operates in 63 cities across 16 countries (Viswanath & Basu, 2015).

Commercial providers such as Uber are also responding with new features to enhance user safety. Uber and Lyft, for example, have incorporated safety feature in their apps, such as an option to call 911. Uber’s RideCheck and Google Maps’ Stay Safer let a rider know if the driver deviates from the projected route. And Uber’s “Follow My Ride” allows friends and family to track a user’s trip.

Drivers also need enhanced safety. In its 2019 report, Uber found that drivers filed 42 percent of sexual assaults reports (Uber, 2019). Uber is experimenting with in-auto audio and video recording services to keep drivers safe, but numerous privacy and other concerns have delayed various solutions.

Conclusions

Numerous innovations seek to integrate gender-sensitive and diversity-sensitive data into the design and development of smart mobility. These methods include co-creation and participatory research which gathers both quantitative and qualitative feedback from users—early in the design process—in order to understand the range of their needs.

Next Steps

1. Implement the emerging tools that incorporate gender-sensitive and diversity-sensitive approaches into all smart mobility projects.

2. Provide guidelines to allow for gender-sensitive and diversity-sensitive data collection, and the assessment of data collected on user attitudes and behaviors. Design new services using participatory methods that integrate gender analysis.

3. Provide guidelines for gender-sensitive and diversity-sensitive collection and assessment of National Travel Survey (NTS) data.

4. Investigate how experienced or feared bullying or violence impacts the travel behavior of women, the elderly, transgender, and gender nonconforming individuals (Lubitow et al., 2017; Ceccato & Loukaitou-Sideris, 2020), and develop countermeasures.

Policy Recommendations

1. Disseminate existing research and best practices.

2. Create guidelines and manuals to improve gender-sensitive planning for new services and the adaptation of existing services.

3. Promote the engagement of relevant stakeholders to support gender-sensitive mobility policies in the city and beyond.

Works Cited

Allen, H. & Alam, M. (2019). Toward Sustainable Mobility: Gender. No. 144535. The World Bank.

Baumann, K. (2010). Personas as a user-centered design method for mobility-related services. Information Design Journal, 18(2), 157-167.

Beyer, S., & Müller, A. (2019). Evaluation of persona-based user scenarios in vehicle development. In T. Ahram, W. Karwowski, & R. Taiar (Eds.), Conference on Human Systems Engineering and Design: Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing (pp. 750-756). Cham: Springer.

Ceccato, V., & Loukaitou-Sideris, A. (Eds.). (2020). Transit Crime and Sexual Violence in Cities: International Evidence and Prevention. London: Routledge.

DIAMOND (2019). https://www.diamond-project.eu

Gebhardt, L., Brost, M., & König, A. (2019). An inter- and transdisciplinary approach to develop and test a new sustainable mobility system. Sustainability, 11(24), 7223.

Giesel, F., & Rahn, C. (2015). Everyday life in the suburbs of Berlin: consequences for the social participation of aged men and women. Journal of Women & Aging, 27(4), 330-351.

Lenz, B. (2020). Smart mobility – for all? Gender issues in the context of new mobility concepts. In T. P. Uteng, L. Levin, H. Rømer Christensen (Eds.), Gendering Smart Mobilities (8-27), Abingdon: Taylor & Francis.

LivingLab 'Reallabor Schorndorf' (2018). https://www.zirius.uni-stuttgart.de/en/projekte/reallabor-schorndorf/ (German)

Lubitow, A., Carathers, J., Kelly, M., & Abelson, M. (2017). Transmobilities: mobility, harassment, and violence experienced by transgender and gender nonconforming public transit riders in Portland, Oregon. Gender, Place & Culture, 24(10), 1398-1418.

Miaskiewicz, T., & Kozar, K. A. (2011). Personas and user-centered design: how can personas benefit product design processes? Design Studies, 32(5), 417- 430.

Nobis, C., & Lenz, B. (2019). Gender differences in using digital mobility services and being mobile. 6th International Conference on Women’s Issues in Transportation.

Nobis, C., & Lenz, B. (2009). Communication and mobility behaviour–a trend and panel analysis of the correlation between mobile phone use and mobility. Journal of Transport Geography, 17(2), 93-103.

Nobis, C., & Lenz, B. (2005). Gender differences in travel patterns: role of employment status and household structure. Research on Women's Issues in Transportation, Report of a Conference, Volume 2: Technical Papers, Transportation Research Board Conference Proceedings, 35, 114-123.

Pruitt, J. S., & Adlin, T. (Eds.) (2006). The Persona Lifecycle: Keeping People in Mind Throughout Product Design. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Sánchez de Madariaga, I., & Zucchini, E. (2019). Measuring mobilities of care, a challenge for transport agendas. In C. L. Scholten & Joelsson, T. (Eds.), Integrating Gender into Transport Planning: From One to Many Tracks (pp. 145-173). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sánchez de Madariaga, I. (2013). The mobility of care: a new concept in urban transportation. In I. Sánchez de Madariaga, & M. Roberts (Eds.), Fair Share Cities: The Impact of Gender Planning in Europe (33-48), London: Ashgate.

Sánchez de Madariaga, I. (2009). Vivienda, movilidad, y urbanismo para la igualdad en la diversidad: ciudades, género, y dependencia. Ciudad y Territorio Estudios Territoriales, XLI (161-162), 581-598.

Tarife, P. M. (2017). Female-only platforms in the ride-sharing economy: discriminatory or necessary? Rutgers University Law Review, 70, 295-334.

Transport Innovation Gender Observatory (TinnGO). https://www.tinngo.eu

Uber Technologies, US Safety Report (San Francisco, 2019).

Viswanath, K., & Basu, A. (2015). SafetiPin: an innovative mobile app to collect data on women's safety in Indian cities. Gender & Development, 23(1), 45-60.

Umweltbundesamt (UBA, 2019): https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/themen/verkehr-laerm/emissionsdaten#handbuch-fur-emissionsfaktoren-hbefa (German).

How can we create public transportation systems that best serve users’ needs?

Gendered Innovations:

1. Reconceptualizing Data Collection. Transportation planners collect data to understand how people use different modes of transport, such as cars, bikes, trains, subways, and buses. The gendered innovation here is to reconceptualize how data are collected and analyzed.

Transportation experts often categorize trips according to purpose to better understand existing transportation patterns and to plan infrastructure changes. The innovative concept “mobility of care” reveals significant travel patterns otherwise concealed in traditional data collection variables.

The charts below represent public transportation trips made in Madrid, Spain, in 2014. The first chart (left) graphs transportation data as traditionally collected and reported. It privileges paid employment by presenting it as a single large category. Caring work (shown in red) is divided into numerous small categories and hidden under other headings, such as escorting, shopping, and leisure. The second chart (right) reconceptualizes public transportation trips by collecting care trips into one category. Visualizing care trips in one dedicated category recognizes the importance of caring work and allows transportation engineers to design systems that work well for broader segments of the population.

Method: Reconceptualizing Data Collection

2. Enhancing Safety for Vulnerable Groups. Numerous innovations surround safety concerns for women, LGBTQ+ individuals, and older people using ride-hailing services. One such innovation is SafetiPin, developed in Delhi, India, in response to the fatal gang rape of a 23-year-old woman in 2012. Using crowdsourced information and safety audits, SafetiPin calculates the safest route between two locations. Safety information can also be shared with city authorities; Delhi, for example, improved lighting in over 5,000 locations in response to user data. SafetiPin now operates in 63 cities across 16 countries.