Sex, Gender, & Intersectional Analysis

Case Studies

- Science

- Health & Medicine

- Chronic Pain

- Colorectal Cancer

- Covid-19

- De-Gendering the Knee

- Dietary Assessment Method

- Gendered-Related Variables

- Heart Disease in Diverse Populations

- Medical Technology

- Nanomedicine

- Nanotechnology-Based Screening for HPV

- Nutrigenomics

- Osteoporosis Research in Men

- Prescription Drugs

- Systems Biology

- Engineering

- Assistive Technologies for the Elderly

- Domestic Robots

- Extended Virtual Reality

- Facial Recognition

- Gendering Social Robots

- Haptic Technology

- HIV Microbicides

- Inclusive Crash Test Dummies

- Human Thorax Model

- Machine Learning

- Machine Translation

- Making Machines Talk

- Video Games

- Virtual Assistants and Chatbots

- Environment

Menstrual Cups: Life-Cycle Assessment

The Challenge

Menstrual products, such as tampons and pads, cost consumers US$26 billion globally in 2019 (Imarc, 2020). At the same time, 49.8 billion tampons and sanitary pads plus their packaging end up in landfills or sewer systems each year in the U.S., meaning that the economic and environmental cost of these products is high. Can the menstrual cup help solve both problems? Can a change in menstrual hygiene sanitation help achieve the United Nations' Sustainable Development goals #5 "gender equality" and #6 "clean water and sanitation" by the year 2030? Can we promote two social goods: both gender equality and environmental sustainability?

Method: Environmental Life-Cycle Assessment

Life-cycle assessments analyze the environmental impacts of a product throughout its life cycle from growing, extracting, and processing raw materials, manufacturing, transportation and distribution, and recycling or final disposal. Environmental sciences should develop comparative life-cycle assessments for each type of menstrual product. Manufacturers should provide assessment results on product labels, enabling consumers to consider environment costs in their decision making.

Gendered Innovations:

- 1. Menstrual Cups are Good for the Environment, supporting the UN Sustainable Development Goals #6 Clean Water and Sanitation

- 2. Menstrual Cups are Good for Gender Equity, supporting the UN Sustainable Development Goals #5 Gender Equality

- 3. Menstrual Cups are Good for Menstruators' Health, supporting the UN Sustainable Development Goals #3 Good Health & Well-Being

- 4. Menstrual Cups are Good for Sustaining School Attendance in Developing Countries, supporting the UN Sustainable Development Goals #1 No Poverty

Conclusions

The Challenge

Menstrual hygiene products, such as tampons and pads, cost consumers US$ 26 billion globally in 2019 (Imarc, 2020). At the same time, 49.8 billion tampons and sanitary pads plus their packaging end up in landfills or sewer systems each year in the U.S. The cost of these products to the consumer and the environment is high. Can the menstrual cup help solve both problems? Can a change in menstrual hygiene sanitation help achieve the United Nations' Sustainable Development goals #5 "gender equality" and #6 "clean water and sanitation" by the year 2030? Can we promote two social goods: both gender equality and environmental sustainability?

The gendered innovation here is the menstrual cup. Although originally patented in 1867 (US 70843 A) and again in 1932 and 1937, menstrual cups have only recently become popular.

A menstrual cup:

- 1. is a bell-shaped and made of medical-grade silicone or natural latex. It is inserted into the vagina to collect (not absorb) menstrual fluid.

- 2. can be left in place for up to 12 hours.

- 3. may last for 2-4 years; some may last up to 10 years.

- 4. is reusable. A user will likely need between 4 and 32 cups in a lifetime, depending on the type used.

- 5. must be washed between uses and be sterilized at the end of the period. Cups can be sterilized in boiling water, microwaves, or, when traveling, with sterilizing tablets.

- 6. is not biodegradable but can be recycled at a specialty recycling center (Thiele, 2016).

- 7. is multifunctional. It can deliver contraception, vaginal medication, and, when a microbicide is added, protect against STIs and HIV. It may also function as a fertility aid by retaining semen close to the cervix (North & Oldham, 2011).

- 8. can be used by all people who menstruate.

- 9. cannot be used by people who have undergone genital cutting and been sewn closed—as is the case for 200 million girls and women worldwide (WHO, 2018).

- 10. is a safe option for menstruation management. It does not cause mechanical harm to the vagina or cervix nor does it increase the risk of infection compared to pads and tampons (van Eijk et al., 2019). However, a menstrual cup may dislodge an IUD, but more research is needed that analyzes factors such as age, menstrual cup removal technique, pelvic anatomy, IUD type, and measures such as cutting the IUD strings short or the need to delay menstrual cup use for a period post-insertion (Bowman & Thwaites, 2023).

- 11. is an effective option for menstruation management. Leakage has been shown to be similar or less with a menstrual cup than with disposable pads/tampons (van Eijk et al., 2019).

N.B. Menstruation is a fact of life. We want to make clear that menstrual products constitute only a small proportion of waste created globally each year. The purpose of this case study is to encourage manufacturers to provide products that are safe and effective—from the point of view of environmental impact, cost, and health.

1: Menstrual Cups are Good for the Environment

supporting the UN Sustainable Development Goals #6 Clean Water and Sanitation

Traditional hygiene products, such as tampons and pads, are a burden to the environment. Altogether a menstruator likely uses around 15,000 sanitary pads or napkins, creating some 250-300 pounds of waste, over a lifetime (Stein, 2009, 238).

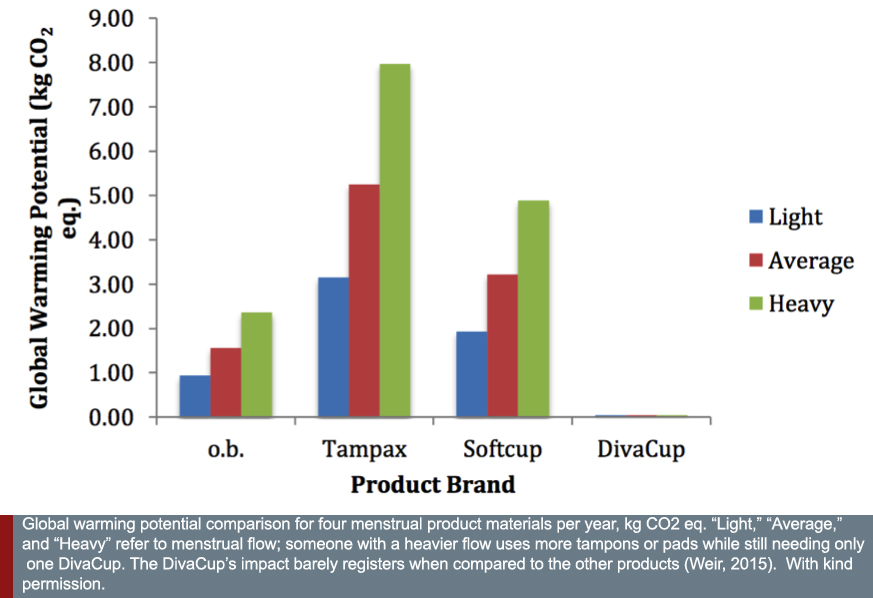

The figure (right) compares the environmental impacts of four products—o.b. tampons (non-reusable, no applicator), Tampax tampon (non-reusable, applicator), Softcup (non-reusable), and DivaCup (reu sable) as indexed by 'global warming potential'. Overall, reusable menstrual cups have the lightest environmental touch (Weir, 2015).

The figure (right) compares the environmental impacts of four products—o.b. tampons (non-reusable, no applicator), Tampax tampon (non-reusable, applicator), Softcup (non-reusable), and DivaCup (reu sable) as indexed by 'global warming potential'. Overall, reusable menstrual cups have the lightest environmental touch (Weir, 2015).

This study also analyzed material impacts by abiotic depletion, fossil fuel depletion, acidification, eutrophication, and waste production. In each category, reusable menstrual cups were the most environmentally friendly.

These data, however, do not factor in all environmental costs across all stages of production, distribution, use, and disposal. A new model study provides an environmental life-cycle assessment that analyzes menstrual products from raw material extraction, transport, production, parts production, and assembly to its use and final disposal. For example, cotton used in many tampons and napkins requires significant land use, water, and pesticides to grow. This study compared the sustainability of six menstrual products: pads (organic and non-organic), tampons (organic and non-organic) menstrual cups, and menstrual underwear across three countries: the U.S., France, and India. Both menstrual cups and menstrual underwear were the most sustainable, even in scenarios where they were used together (menstruators’ may backup the cups with menstrual underwear—Fourcassier et al., 2022).

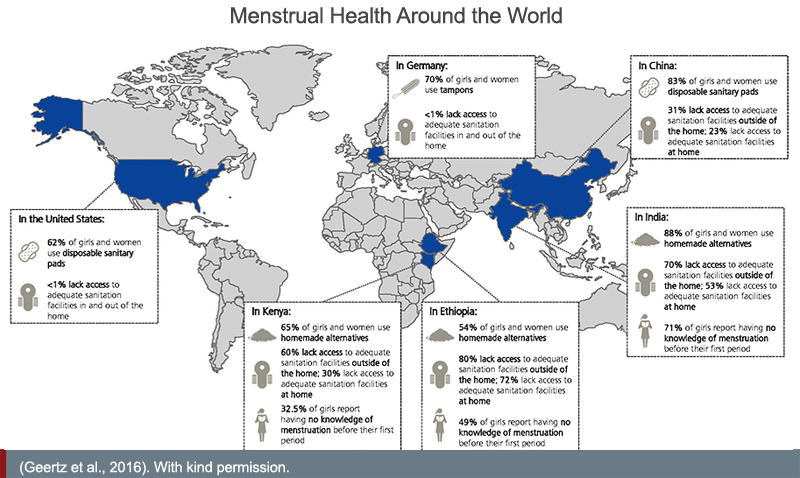

The environmental impact of pads and tampons is growing. In India, for example, only 12% of the 335 million women currently use sanitary napkins (Geertz et al., 2016). What will happen when 100% of those in their reproductive years achieve sanitary protection across India, Africa, and China (the last of which currently manufactures 85 billion sanitary napkins each year—Yang, 2016)?

Some traditional sanitary products are biodegradable, but the vast majority are made from synthetic materials that decompose slowly. Some 90 percent of sanitary napkins are plastic (Women's Environmental Network, 2017). It is estimated that the 20 billion pads, tampons, and applicators accumulating in North American landfills every year will take 500 to 800 years to fully biodegrade (Geertz et al., 2016, 12).

2: Menstrual Cups are Good for Gender Equality

supporting the UN Sustainable Development Goals #5 Gender Equality

In 2019, Menstrual hygiene products, such as tampons and pads, cost consumers US$ 26 billion globally (Imarc, 2020). These costs magnify gender inequality given the gender pay gap (women in the U.S. overall earn 80.5 cents on men's dollars). These costs especially burden low-income people, creating a barrier to accessing menstrual sanitary products. U.S. aid programs, such as Medicaid, do not support menstrual products, even though the FDA considers them medical devices (Kosin, 2018).

Although the cup is more expensive upfront (roughly U.S. $15-25 depending on the brand), because it is reusable it saves thousands of dollars over a lifetime. In qualitative studies, participants using menstrual cups cite monthly savings from not needing to buy pads or laundry soap (van Eijk et al., 2019). In addition, emerging evidence indicates that menstrual cup use in resource-poor areas might decrease the need for transactional sex to purchase feminine hygiene products (van Eijk et al., 2019).

A conservative estimate would project the cost of menstrual cup use to be as low as US$180 for cups (assuming 3 cups per decade x 4 decades) and not more than $430 (assuming 8 cups x 4 decades) plus government tax (in countries that still charge tax). The initial investment may be high because of the possible need to purchase several cups before finding the right fit.

3: Menstrual Cups are Good for Health

supporting the UN Sustainable Development Goals #3 Good Health & Well-Being

The U.S. FDA recommends but does not require tampon and sanitary pad makers to disclose the materials and chemicals in their products (FDA, 2005). People may be unaware of potential toxins, in particular dioxin, contained in these products (WHO, 2016). Although the FDA considers the threat from dioxins in tampons "negligible," no studies have tested diffusion of dioxins from tampons in vivo or the accumulative impact of exposure over a lifetime (Weir, 2015; Dudley et al., 2018). Further, tampons and pads carry the threat of toxic shock syndrome (Wendee, 2014).

Menstrual cups, by contrast, are hypoallergenic and bear a very low reported risk of TSS; medical grade silicone does not significantly support the growth of the bacterium S. aureus, associated with TSS (Tierno, 1994; North & Oldham, 2011; van Eijk et al., 2019).

A cluster randomized control study in rural Western Kenya found other health benefits. Menstrual cups can also be used to deliver contraception, vaginal medication, and, when a microbicide is added, protection against STIs and HIV. (North & Oldham, 2011; Phillips-Howard et al., 2016).

4: Menstrual Cups Help Sustain School Attendance in Developing Countries

supporting the UN Sustainable Development Goals #1 No Poverty

Menstrual hygiene products can be prohibitively expensive in low-income settings, such as parts of the U.S., sub-Saharan Africa, and rural India. As a result, people may use reusable cloth, newspaper, or simply stay home (Sommer & Sahin, 2013).

A number of recent projects have studied the impact of introducing menstrual cups to school-age children in South Africa, Uganda, Kenya, and rural India. Participants were provided a cup, education on menstruation and cup use, and a bar of soap each month plus information on how to disinfect cups (although many lacked the simple equipment required to boil cups—Hyttel et al, 2017). Studies found that, with proper education and training, participants successfully used the cups, and often preferred them to pads (Howard et al., 2011; Beksinska et al., 2015; Mason et al., 2015).

Cups had several advantages: menstrual cups reduced fear of leaking, increased confidence, comfort, mobility, independence, and allowed active school attendance or work during menstruation; a UK study found that menstrual cup use was associated with a significant decrease in the number of product changes in one cycle when compared to tampons and pads (van Eijk et al., 2019).

The cost of any menstrual hygiene products is prohibitive in many areas. Some cup brands, such as Femmecup, Ruby Cup, Keeper, Diva cup, Lunette, Softcup, and My Own Cup, have programs to donate to people in need.

Conclusions

Menstruation is a fact of life. But the way societies manage and respond to menstruation can and are being changed. Proper management requires changing attitudes and making menstruation a topic people feel comfortable talking about and taking action on menstruation. Education, support, and sanitation infrastructure are all important. The goal is comfortable, convenient products that are safe for people and the environment.

Next Steps

- 1. For environmental sciences, comparative life-cycle assessment is required for each type of menstrual product. These analyses should factor in all environmental costs across all stages of production, distribution, use, and disposal. On packaging, manufacturers should provide results from such a life-cycle analysis for the specific product, indicating environmental impacts from raw material extraction, material production, parts production and transportation, and assembly to its use and final disposal.

-

2. Product designers can provide alternatives to traditional menstrual hygiene products. Current initiatives:

- a. Thinx and Dear Kate produce high-tech washable underwear that absorbs menstrual fluid. The fabric is anti-microbial, moisture-wicking, absorbent, and leak resistant (https://www.shethinx.com; http://www.dearkate.com). TomboyX and other companies also gender-inclusive period underwear in sizes appropriate also for transgender men and others. We caution our readers that Thinx was recently sued for containing harmful chemicals, specifically per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, known as PFAS or “forever chemicals” (Gupta, 2023).

- b. Sustainable Health Enterprises train people to make pads out of banana trunk fibers (http://sheinnovates.com).

- c. AFRIpads produce washable reusable pads across Africa (https://www.afripads.com).

- d. BeGirl makes reusable underwear with a mesh pocket that can be filled with any readily available, safe absorbent material (https://www.begirl.org).

- e. Femme International's Femme Health Management initiative distributes menstrual cups, menstrual education, and other hygiene products in East Africa (https://www.femmeinternational.org/our-work/).

- 3. Politicians should support human rights with respect to menstruation. Human Rights Watch and WASH United have stated that the biological fact of menstruation, the necessity of managing menstruation, and society's response to both are linked to human rights and gender equality (Human Rights Watch, 2017). Chief of the UN Human Rights Office Economic and Social Issues Section, Jyoti Sanghera, adds that "stigma around menstruation and menstrual hygiene is a violation of several human rights" (UNOHCHR, 2014). ). In 2020, Scotland is the first country in the world to offer free menstrual products to anyone who needs them to overcome menstrual poverty (Diamond, 2022). The idea is that menstruators should not have to pay for and be taxed on these biologically necessary products. An important question is: What products are they offering? It is important that these products be reusable or biodegradable—i.e., fully sustainable.

- 4. Foundations can support access to sustainable menstruation products. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, for example, advocates for addressing menstruation sustainably and at scale (Geertz et al, 2016). This includes safe and consistent access to products, supportive communities, education and awareness, and excellent sanitation facilities and services.

Works Cited

BBC News (2017). Tampon tax: How much have you spent? BBC News. http://www.bbc.com/news/health-42013239 Downloaded Feb 7, 2018.

Beksinska, M. E., Smit, J., Greener, R., Todd, C. S., Lee, M. L. T., Maphumulo, V., & Hoffmann, V. (2015). Acceptability and performance of the menstrual cup in South Africa: a randomized crossover trial comparing the menstrual cup to tampons or sanitary pads. Journal of Women's Health, 24(2), 151-158.

Bowman, N. & Thwaites, A. (2023). Menstrual cup and risk of IUD expulsion–a systematic review. Contraception and reproductive medicine, 8(1), 15.

Diamond, Claire. Period poverty: Scotland first in world to make period products free. BBC News, 15 August 2022. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-scotland-politics-51629880.

Dudley, S., Nassar, S., Hartman, E., & Wang, S. (2018). Tampon safety. National Center for Health Research. http://www.center4research.org/tampon-safety.

Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2005). Guidance for industry and FDA staff. Menstrual tampons and pads: Information for premarket notification submissions. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Fourcassier, S., Douziech, M., Pérez-López, P., & Schiebinger, L. (2022). Menstrual products: A comparable Life Cycle Assessment. Cleaner Environmental Systems, 7, 100096.

Geertz, A., Iyer, I., Kasen, P., Mazzola, F., & Peterson, K. (2016). An Opportunity to Address Menstrual Health and Gender Equity. FSG.

Gupta, A. H. (2023), What to know about PFAS in period underwear, New York Times, Jan 20, 2023.

Human Rights Watch (2017). Understanding Menstrual Hygiene Management & Human Rights. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/mhm_practitioner_guide_web.pdf

Howard, C., Rose, C. L., Trouton, K., Stamm, H., Marentette, D., Kirkpatrick, N., ... & Paget, J. (2011). FLOW (finding lasting options for women). Canadian Family Physician, 57(6), e208-e215.

Hyttel, M., Thomsen, C. F., Luff, B., Storrusten, H., Nyakato, V. N., & Tellier, M. (2017). Drivers and challenges to use of menstrual cups among schoolgirls in rural Uganda: a qualitative study. Waterlines, 36(2), 109-124.

Imarc, Feminine Hygience Products Market: Global Industry Trends, Share, Size, Growth, Opportunity and Forecast 2020-2025. https://www.imarcgroup.com/feminine-hygiene-products-market Accessed 2 January 2021.

Kosin, J. (2018, May 3) Getting Your Period Is Still Oppressive in the United States. Harper's Bazaar.

Mason, L., Laserson, K., Oruko, K., Nyothach, E., Alexander, K., Odhiambo, F., ... & Mohammed, A. (2015). Adolescent schoolgirls' experiences of menstrual cups and pads in rural western Kenya: a qualitative study. Waterlines, 34(1), 15-30.

North, B. B., & Oldham, M. J. (2011). Preclinical, clinical, and over-the-counter postmarketing experience with a new vaginal cup: menstrual collection. Journal of Women's Health, 20(2), 303-311.

Phillips-Howard, P. A., Nyothach, E., ter Kuile, F. O., Omoto, J., Wang, D., Zeh, C., ... & Eleveld, A. (2016). Menstrual cups and sanitary pads to reduce school attrition, and sexually transmitted and reproductive tract infections: a cluster randomised controlled feasibility study in rural western Kenya. BMJ open, 6(11), e013229.

Prima Citta, S., Uehara, T., Cordier, M., Tsuge, T. & Asari, M. (2024). Promoting menstrual cups as a sustainable alternative: a comparative study using a labeled discrete choice experiment. Frontiers in Sustainability, 5, 1391491.

Sommer, M., & Sahin, M. (2013). Overcoming the taboo: advancing the global agenda for menstrual hygiene management for schoolgirls. American journal of public health, 103(9), 1556-1559.

Stein, Elissa, and Susan Kim. (2009). Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation. St. Martin's Griffin.

Thiele, L. (2016). How to Recycle a Menstrual Cup. Ruby Cup. http://rubycup.com/blog/how-to-recycle-a-menstrual-cup/

Tierno, P., & Hanna, B. (1994). Propensity of tampons and barrier contraceptives to amplify staphylococcus aureus toxic shock syndrome toxin-i. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology2, 140-45.

United Nations Environmental Programme (2021). Single-use menstrual products and their alternatives: Recommendations from Life Cycle Assessments.

United Nations Human Rights Office of The High Commissioner (2014). Every woman's right to water, sanitation, and hygiene http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/Everywomansrighttowatersanitationandhygiene.aspx Retrieved February 21, 2018.

Van Eijk, A. M., Zulaika, G., Lenchner, M., Mason, L., Muthusamy, S., Nyothach, E., … Phillips-Howard, P. (2019). Menstrual cup use, leakage, acceptability, safety, and availability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30111-2

Weir, C.M (2015). In The Red: A private economic cost and qualitative analysis of environmental and health implications for five menstrual products. Environmental Science and Gender and Women Studies, Dalhousie University, Canada. Thesis supervised by Tarah Wright, Environmental Studies, and Peter Tyedmers, School of Resource and Environmental Studies, Dalhousie University.

Wendee, N. (2014). A question for women's health: Chemicals in feminine hygiene products and personal lubricants. Environmental Health Perspectives. 122, no. 3, A70.

Women's Environmental Network (2017). Periods are natural. Bleached plastic sanitary products aren't. https://www.wen.org.uk/environmenstrual/ Downloaded Feb 7, 2018.

World Health Organization (2018). Female genital mutilation: Fact sheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs241/en/ Downloaded Feb 9, 2018.

World Health Organization. (2016). Dioxins and their effects on human health. Fact sheets. http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dioxins-and-their-effects-on-human-health.

Yang, Y. (2016). China made 85 billion sanitary pads last year, and not one tampon. Here's why. LATimes.

Menstrual hygiene products, such as tampons and pads, cost U.S. consumers US$26 billion globally in 2019 (Imarc, 2020). At the same time, 49.8 billion tampons and sanitary pads plus their packaging end up in landfills or sewer systems each year in the U.S., meaning that the economic and environmental cost of these products is high. Can the menstrual cup help solve both problems? Can a change in menstrual hygiene sanitation help achieve the United Nations' Sustainable Development goals #5 "gender equality" and #6 "clean water and sanitation" by the year 2030? Can we promote two social goods: gender equality and environmental sustainability?

Menstrual cups are made of medical-grade silicone or natural latex and inserted into the vagina to collect (not absorb) menstrual fluid. They can be left in place for up to 12 hours. The advantage over tampons and pads is that they are reusable and last for 4 to possibly 10 years. Because a user only needs a handful of cups over a lifetime, they are much less expensive than tampons and pads.

Menstrual cups may also help sustain school attendance in developing countries. Menstrual hygiene products can be prohibitively expensive in low-income settings, such as parts of the U.S., sub-Saharan Africa, and rural India. As a result, some people may stay home from school. Menstrual cups may increase confidence, comfort, mobility, independence, and school attendance.

Menstrual cups can also be used to deliver contraception, vaginal medication, and, when a microbicide is added, protection against STIs and HIV. They are hypoallergenic and bear a very low reported risk of Toxic Shock Syndrome.

The purpose of this case study is to encourage manufacturers to provide products that are safe and effective —from the point of view of environmental impact, cost, and health.

Gendered Innovations:

- 1. Menstrual cups are good for the environment because they reduce waste, and support the UN Sustainable Development Goals #6 Clean Water and Sanitation.

- 2. Menstrual cups are good for gender equity because they reduce cost and encourage school attendance. They also support the UN Sustainable Development Goals #5 Gender Equality.

- 3. Menstrual cups are good for women's health, supporting the UN Sustainable Development Goals #3 Good Health & Well-Being.

- 4. Menstrual Cups Help Sustain School Attendance in Developing Countries, supporting the UN Sustainable Development Goals #1 No Poverty.