Gender refers to sociocultural norms, identities, and relations that: 1) structure societies and organizations; and 2) shape behaviors, products, technologies, environments, and knowledges (Schiebinger, 1999). Gender attitudes and behaviors are complex and change across time and place. Importantly, gender is multidimensional (Hyde et al., 2018) and intersects with other social categories, such as sex, age, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation and ethnicity (see Intersectional Approaches). Gender is distinct from sex (Fausto-Sterling, 2012).

Three Related Dimensions of Gender:

As social beings, humans function through learned behaviors. How we speak, our mannerisms, the things we use, and our behaviors all signal who we are and establish rules for interaction. Gender is one such set of organizing principles that structure behaviors, attitudes, physical appearance, and habits.

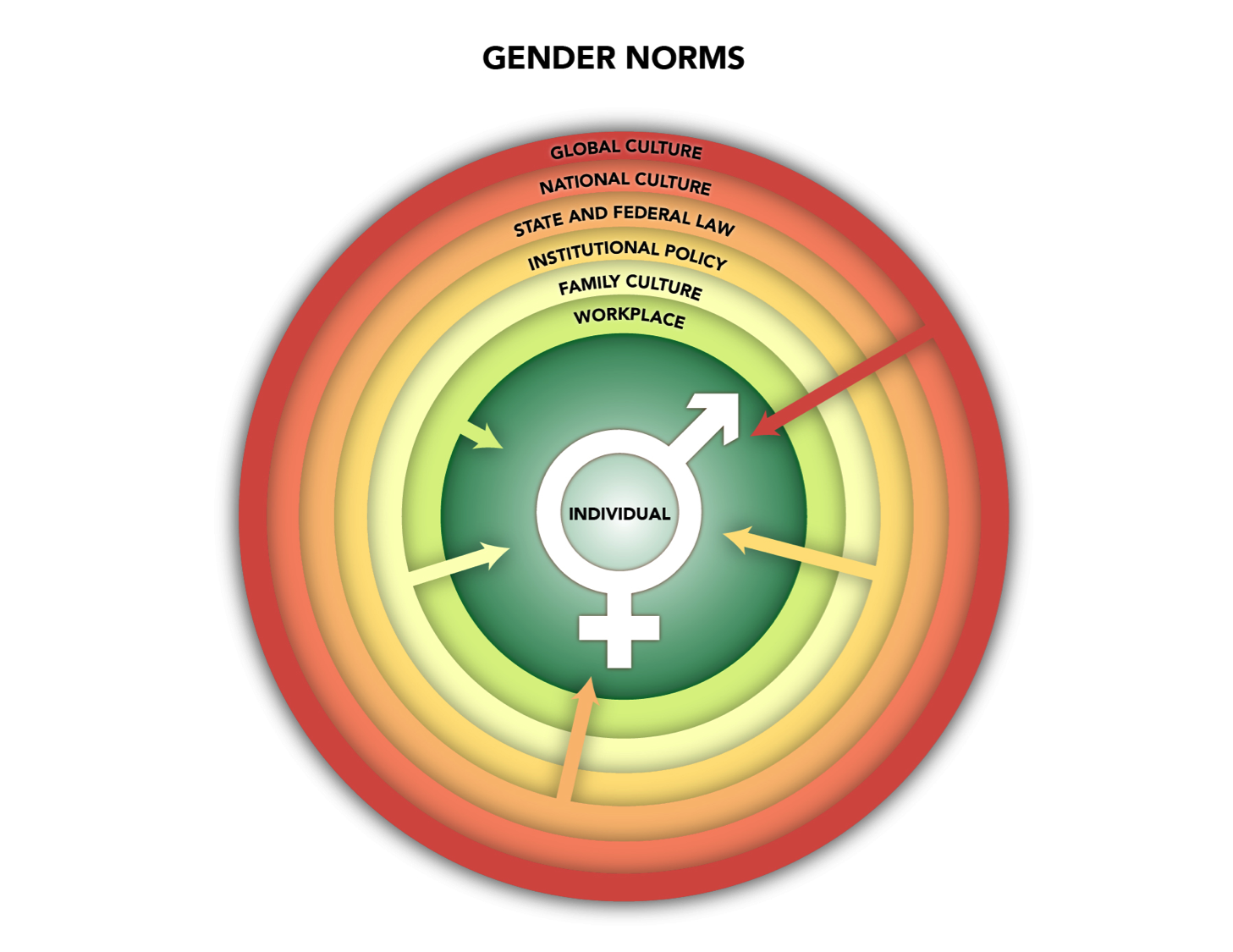

1. Gender Norms are produced through social institutions (such as families, schools, workplaces, laboratories, universities or boardrooms), social interactions (such as between romantic partners, work colleagues, or family members), and wider cultural products (such as textbooks, literature, film and video games).

1. Gender Norms are produced through social institutions (such as families, schools, workplaces, laboratories, universities or boardrooms), social interactions (such as between romantic partners, work colleagues, or family members), and wider cultural products (such as textbooks, literature, film and video games).

- ● Gender norms refer to social and cultural attitudes and expectations about which behaviors, preferences, products, professions or knowledges are appropriate for women, men and gender-diverse individuals, and may influence the development of science and technology.

- ● Gender norms draw upon and reinforce gender stereotypes about women, men and gender-diverse individuals.

- ● Gender norms may be reinforced by unequal distribution of resources and discrimination in the workplace, families and other institutions.

-

● Gender norms are constantly in flux. They change by historical era, culture or location, such as the 1950s versus the 2020s, Korea versus Germany, or urban versus rural areas. Gender also differs by specific social contexts, such as work versus home.

● Gender norms are constantly in flux. They change by historical era, culture or location, such as the 1950s versus the 2020s, Korea versus Germany, or urban versus rural areas. Gender also differs by specific social contexts, such as work versus home.

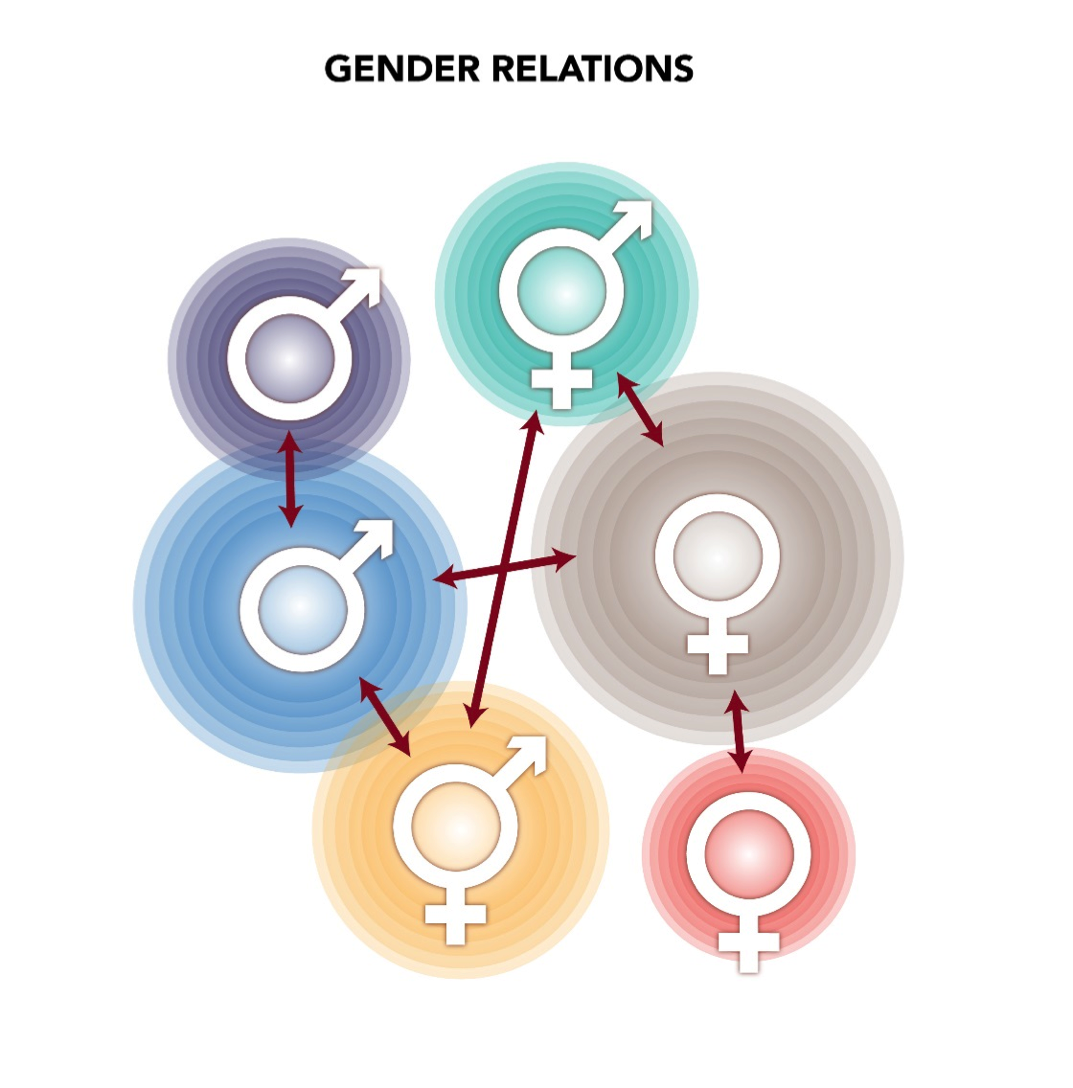

3. Gender Relations refer to how we interact with people and institutions in the world around us, based on our sex and our gender identity. Gender relations encompass how gender shapes social interactions in families, schools, workplaces and public settings, for instance, the power relation between a man patient and woman physician.

3. Gender Relations refer to how we interact with people and institutions in the world around us, based on our sex and our gender identity. Gender relations encompass how gender shapes social interactions in families, schools, workplaces and public settings, for instance, the power relation between a man patient and woman physician.

- ●Social divisions of labor are another important aspect of gender relations, where women and men are concentrated in different types of (paid or unpaid) activities. One consequence of such gender segregation is that particular occupations or disciplines become marked symbolically with the (presumed) gender category of the larger group: for example, nursing is seen as a female profession, engineering as male.

- ● Women and men who work in highly segregated roles acquire different kinds of knowledge or expertise, which can sometimes be usefully accessed for gendered innovations (see Co-Creation and Participatory Research; see also Case Study: Water Infrastructure).

- ● Gender relations can also become embodied in products or urban environments, such as transportation systems (see Case Study: Smart Mobility).

Sex and gender interact: The term gender was introduced in the late 1960s to reject biological determinism that interprets behavioral differences as the outcomes of biological disposition. “Gender” was used to distinguish the sociocultural factors that shape behaviors and attitudes from biological factors related to sex. Gendered behaviors and attitudes are learned; they are neither fixed nor universal. Gendered experiences can affect biology. Moreover, some individuals seek to change aspects of their bodies to align them better with their gender identities. Sex and gender are often useful analytical terms even if in reality sex and gender interact (see Method: Analyzing how Sex and Gender Interact).

Sex and gender interact: The term gender was introduced in the late 1960s to reject biological determinism that interprets behavioral differences as the outcomes of biological disposition. “Gender” was used to distinguish the sociocultural factors that shape behaviors and attitudes from biological factors related to sex. Gendered behaviors and attitudes are learned; they are neither fixed nor universal. Gendered experiences can affect biology. Moreover, some individuals seek to change aspects of their bodies to align them better with their gender identities. Sex and gender are often useful analytical terms even if in reality sex and gender interact (see Method: Analyzing how Sex and Gender Interact).

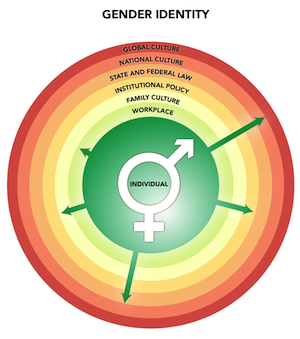

Legal gender categories: Governments typically require citizens to categorize their gender identity on official documents such as birth certificates, driving licenses and passports. Numerous countries recognize a third gender category. These include Argentina, Australia, Bangladesh, Canada, Colombia, Denmark, Germany, India, Malta, Nepal, New Zealand and Pakistan, among others.

Cisgender and Transgender: Transgender is an umbrella term which describes a range of gender identities, including individuals whose gender identity differs from that typically associated with the sex they were assigned at birth. (Marshall et al., 2019; Scandurra et al., 2019). This is in contrast to cisgender, which describes individuals whose self-identified gender matches their birth sex assignment. The term "cisgender" is used to resist the idea that cisgender is the norm and transgender is not (Aultman, 2014). Other individuals refuse the concept of gender as binary altogether, and may self-identify as genderqueer, nonbinary, genderfluid, or bigender (Hyde et al., 2018).

Gender is multi-dimensional: Gender is often described as existing on a masculinity-femininity spectrum, but such categories can reinforce stereotypes about women and men and ignore individuals who fall outside traditional gender binaries (Nielsen et al., 2020). Gender is multidimensional: any given individual may experience configurations of gender norms, traits, and relations that cannot be subsumed under the simple categories "feminine" or "masculine".

Works Cited

Aultman, B. (2014). Cisgender. Transgender Studies Quarterly, 1 (1-2), 61-62.

Fausto-Sterling, A. (2012). The Dynamic Development of Gender Variability. Journal of Homosexuality, 59, 398-421.

Fausto-Sterling, A. (2012). Sex/Gender: Biology in a Social World. New York: Routledge.

Hyde, J. S., Bigler, R. S., Joel, D., Tate, C. C., & van Anders, S. M. (2018). The future of sex and gender in psychology: Five challenges to the gender binary. American Psychologist, 74(2), 171-193.

Kessler, S. (1990). The Medical Construction of Gender: Case Management of Intersexed Infants. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 16 (1), 3-25.

Marshall, Z., Welch, V., Minichiello, A., Swab, M., Brunger, F., & Kaposy, C. (2019). Documenting Research with Transgender, Nonbinary, and Other Gender Diverse (Trans) Individuals and Communities: Introducing the Global Trans Research Evidence Map. Transgender health, 4(1), 68-80.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2022). Measuring Sex, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26424.

Nielsen, M.W., Peragine, D., Neilands, T. B., Stefanick, M.L., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Pilote, L., Prochaska, J. J., Cullen, M. R., Einstein, G., Klinge, I., LeBlanc, H., Paik, H. Y., Risvedt, S., & Schiebinger, L. (2020), Gender-Related Variables for Health Research, in press.

Ridgeway, Cecilia L., & Correll, Shelley J. (2004). Unpacking the gender system: a theoretical perspective on gender beliefs and social relations. Gender & Society, 18. 510-5.

Scandurra, C., Mezza, F., Maldonato, N. M., Bottone, M., Bochicchio, V., Valerio, P., & Vitelli, R. (2019). Health of non-binary and genderqueer people: A systematic review. Frontiers in psychology, 10.

Schiebinger, L. (1999). Has Feminism Changed Science? Cambridge: Harvard University Press.