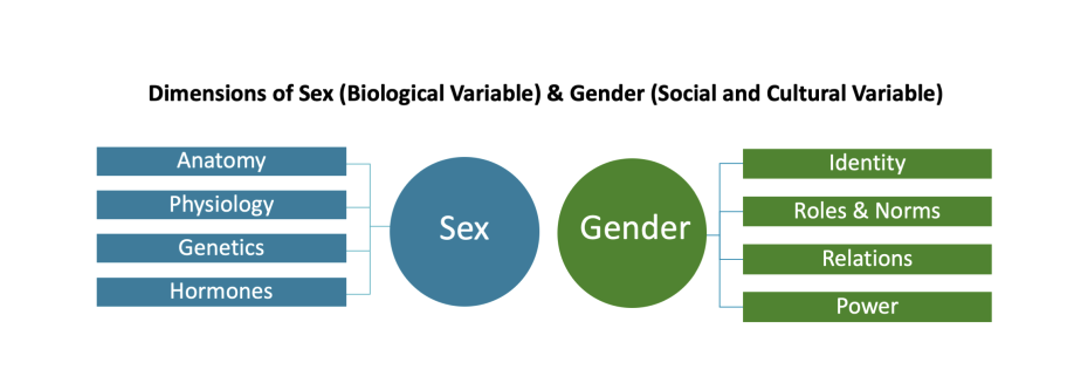

"Sex" and "gender" are distinguished for analytical purposes (see Sex and Gender). In reality, sex and gender interact (mutually shape one another) to form individual bodies, cognitive abilities, and disease patterns, etc. (Nowatzki & Grant, 2011; Fausto-Sterling, 2012; Schiebinger & Stefanick, 2020; Ritz & Greaves, 2022).

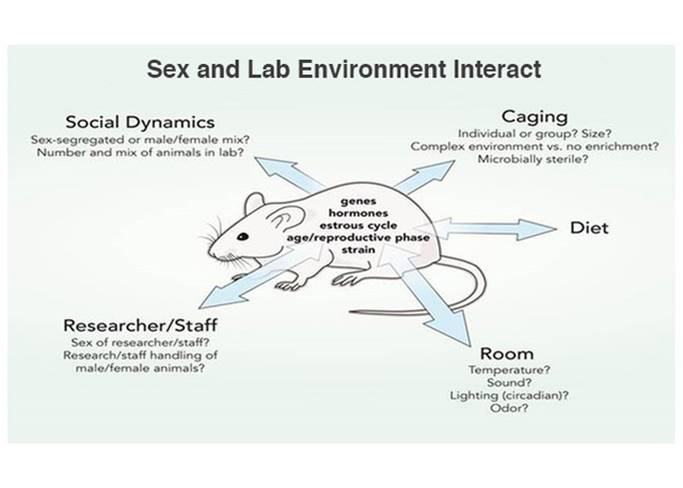

In animal research, interactions between the sexes can shape research outcomes. Consider, for instance, the longevity of the nematode C. elegans. Research demonstrates that the presence of male C. elegans accelerates aging and shortens the life span of individuals of the opposite sex, in this case hermaphrodites (Maures et al., 2014). Most lab-studies of animals examine females, males, and hermaphrodites separately. However, the sexes coexist in their natural environments, and ignoring interactions between them will restrict our knowledge of species viability (Tannenbaum et al., 2019). Similarly, the sex of the experimenter conducting animal studies can moderate an animal’s response to treatment. For instance, research finds that mice are less prone to exhibit pain in the presence of a male experimenter compared to a female experimenter, and that this “male-observer effect” is larger in female than in male mice (Sorge et al., 2014—see Method: Analyzing Sex in Lab Animal Research). In this case, the animals don’t show pain when exposed to male pheromones. This phenomenon may throw into question all prior results from pain research. Sex and Gender Interact

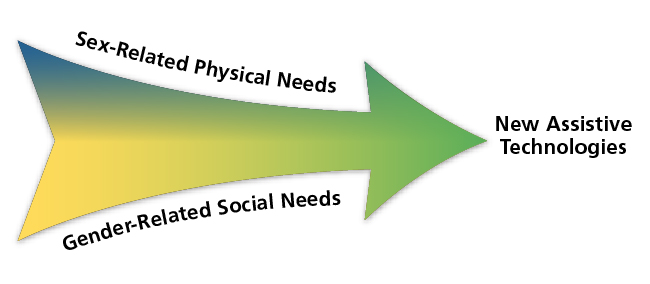

Sex and gender also interact to shape the ways we engineer and design objects, buildings, cities, and infrastructures. Recognizing how gender shapes sex and how sex influences culture is critical to designing quality research.

Example 1: How Sex and Gender interact when Exploring Markets for Assistive Technologies for the Elderly

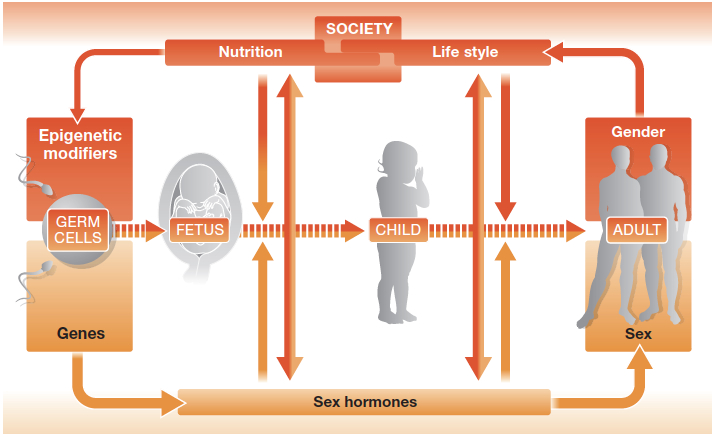

Example 2: How Sex and Gender Interact throughout the Life Course

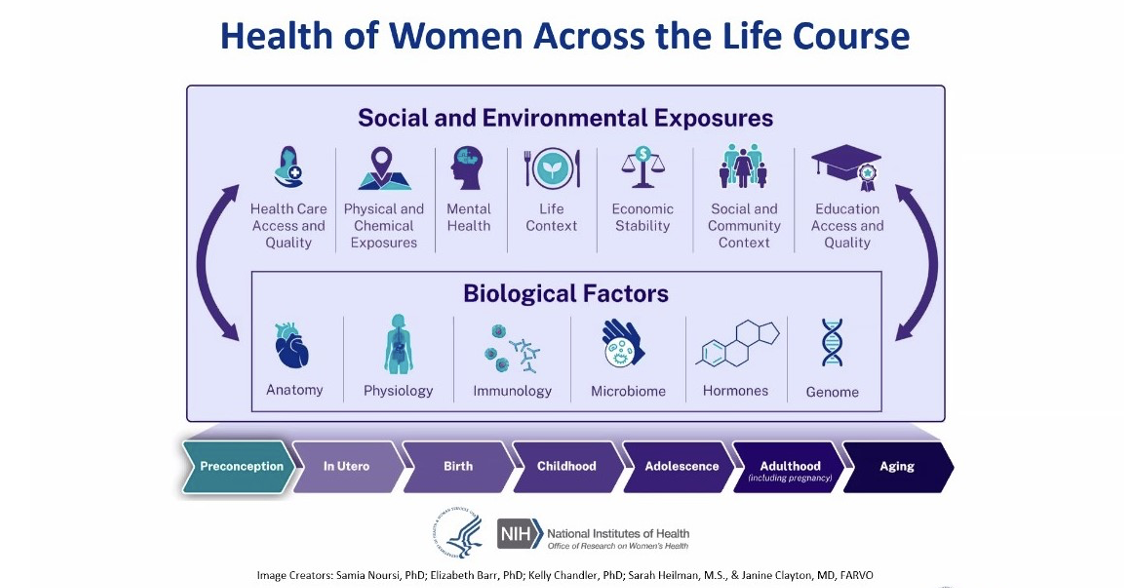

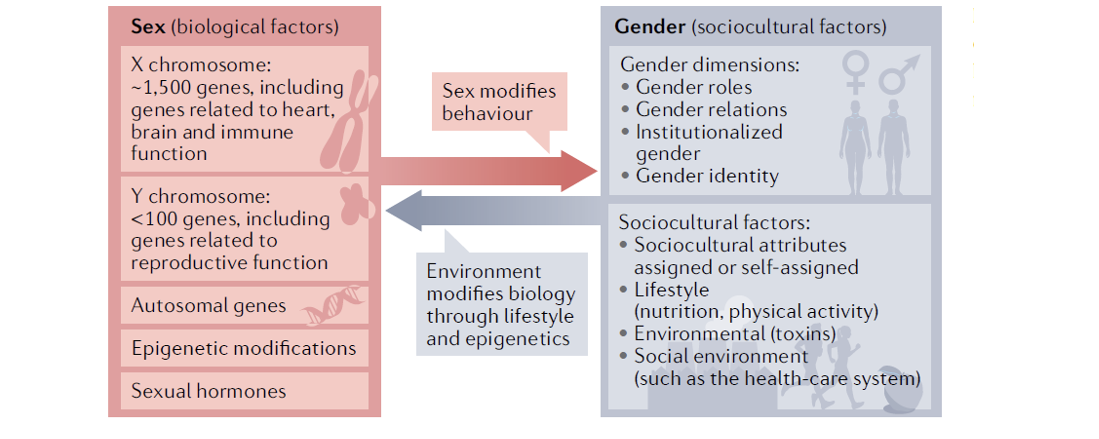

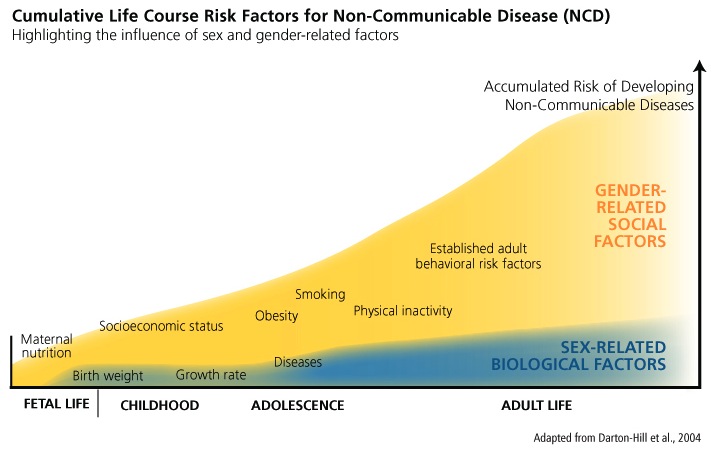

It is important to analyze the complex interdependency of sex and gender across the human life cycle. If we take health status, for example, sex influences health by modifying behavior. At the same time, gender behaviors can modify biological factors.(see Heart Disease in Diverse Populations; Nutrigenomics; Osteoporosis Research in Men).

Image 1:

Regitz-Zagrosek, V. (2012). Sex and Gender Differences in Health. European Molecular Biology Organization Reports, 13 (7), 596-603.

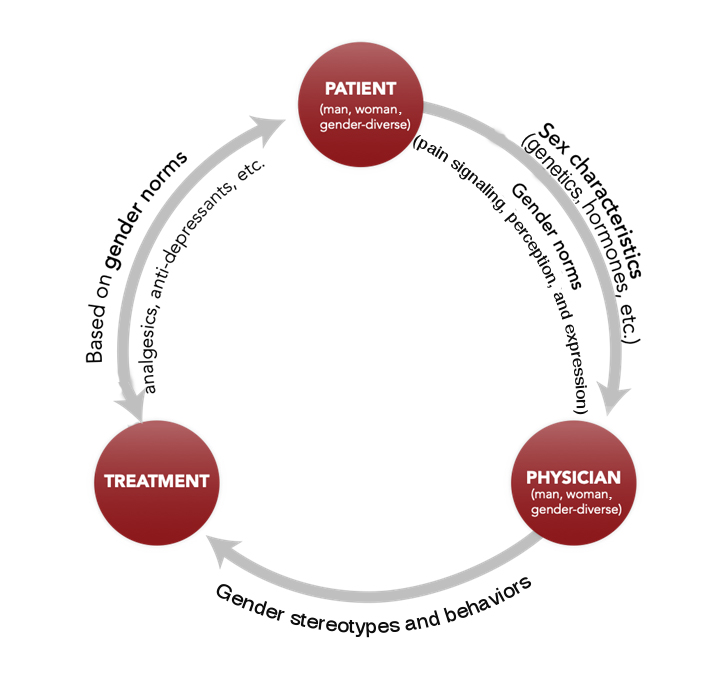

Image 2:

NIH, Office for Research on Women’s Health: Notice of Special Interest: Health Influences of Gender as a Social and Structural Variable

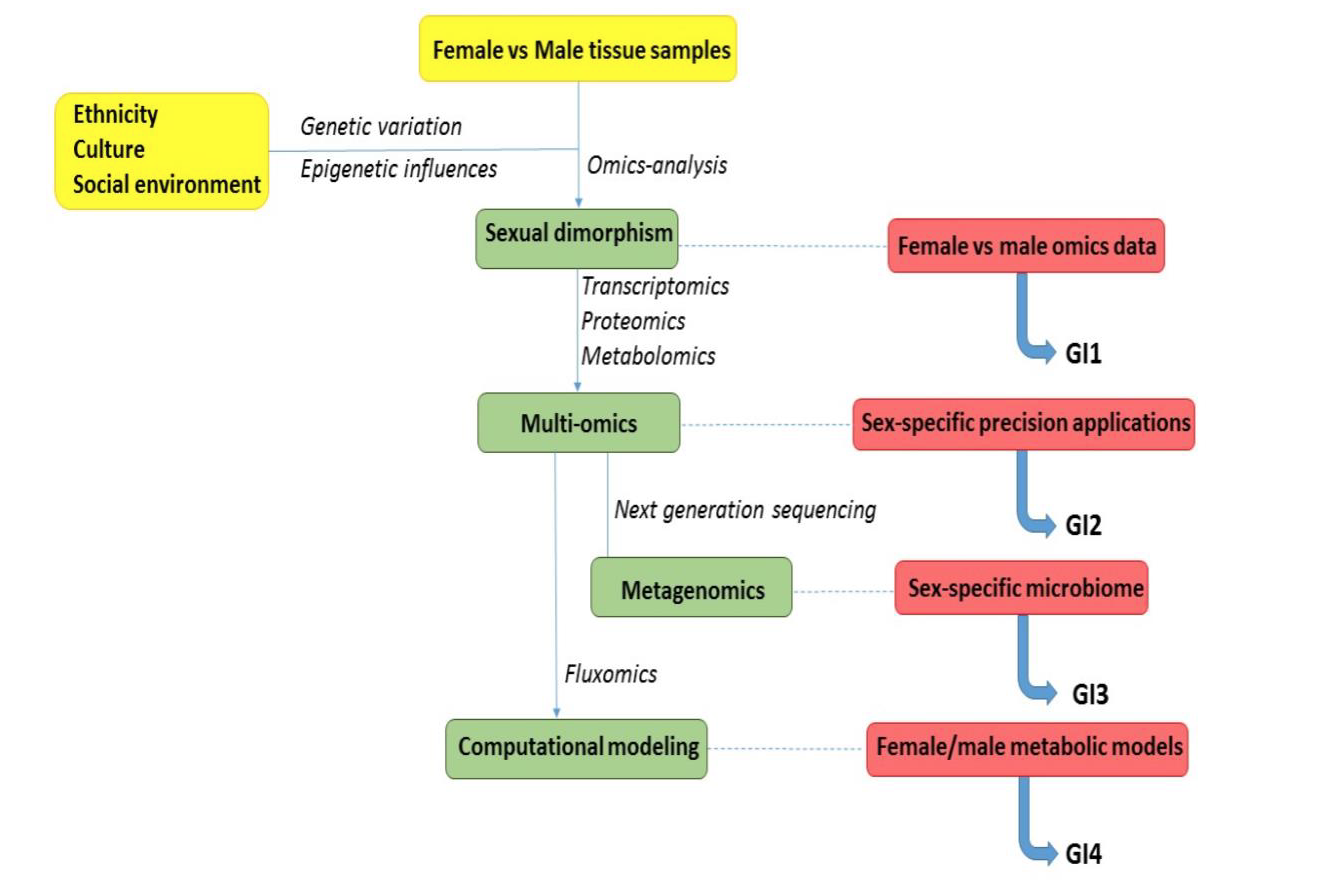

Image 3:

NIH, Office for Research on Women’s health, NIH-Wide Strategic Plan for Research on the Health of Women, 2024-2028

Image 4:

Regitz-Zagrosek, V., & Gebhard, C. (2023). Gender medicine: effects of sex and gender on cardiovascular disease manifestation and outcomes. Nature Reviews Cardiology, 20(4), 236-247.

Example 3: How Sex and Lab Environment Interact in Animal Research

Example 4: How Sex, Gender, and other Factors Interact in Nutrigenomics

Example 5: How Sex, Gender, and other Factors Interact in Pain

Example 6: How Sex and Gender Interact in Systems Biology

Works Cited

Bartley, E. J., & Fillingim, R. B. (2013). Sex differences in pain: a brief review of clinical and experimental findings. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 111, 52–58.

Chapman, C. D., Benedict, C., & Schiöth, H. B. (2018). Experimenter gender and replicability in science. Science Advances, 4(1), doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1701427.

Fausto-Sterling, A. (2012). Sex/Gender: Biology in a Social World. New York: Routledge.

Fine, C. (2017). Testosterone Rex: Unmaking the Myths of Our Gendered Minds. London: Icon Books.

Holmboe, S. A., Priskorn, L., Jørgensen, N., Skakkebaek, N. E., Linneberg, A., Juul, A., & Andersson, A. M. (2017). Influence of marital status on testosterone levels:a ten year follow-up of 1113 men. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 80, 155–161.

Hoffman, K. M., Trawalter, S., Axt, J. R., & Oliver, M. N. (2016). Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(16), 4296-4301.

Kaiser, A. (2015). Re-conceptualizing “sex” and “gender” in the human brain. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 220(2): 130-136.

Krieger, N. Genders, sexes, and health: what are the connections—and why does it matter? (2003). International Journal of Epidemiology, 32, 652–657.

Leopold, S., Beadling, L., Dobbs, M., Gebhardt, M., Lotke, P., Manner, P., Rimnac, C., & Wongworawat, M. (2014). Fairness to All: Gender and Sex in Scientific Reporting. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 472(2), 391-392.

Maures, T. J., Booth, L. N., Benayoun, B. A., Izrayelit, Y., Schroeder, F. C., & Brunet, A. (2014). Males shorten the life span of C. elegans hermaphrodites via secreted compounds. Science, 343(6170), 541-544.

Notwatski, N. & Grant, K. (2011). Sex is not Enough: The Need for Gender Based Analysis in Health Research. Health Care for Women International, 32 (4), 263-277.

Regitz-Zagrosek, V. (2012). Sex and Gender Differences in Health. European Molecular Biology Organization Reports, 13 (7), 596-603.

Ritz, S. A., & Greaves, L. (2022). Transcending the Male–Female Binary in Biomedical Research: Constellations, Heterogeneity, and Mechanism When Considering Sex and Gender. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 4083.

Schiebinger, L. & Stefanick, M. (2020). Analyzing how sex and gender interact. Lancet (forthcoming).

Schwarz, K. A., Sprenger, C., Hidalgo, P., Pfister, R., Diekhof, E. K., & Buchel, C. (2019). How stereotypes affect pain. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 8626. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-45044-y

Sorge, R. E., Martin, L. J., Isbester, K. A., Sotocinal, S. G., Rosen, S., Tuttle, A. H., ... & Leger, P. (2014). Olfactory exposure to males, including men, causes stress and related analgesia in rodents. Nature methods, 11(6), 629.

Springer, K., Stellman, J., & Jordan-Young, R. (2012). Beyond a Category of Differences: A Theoretical Frame and Good Practice Guidelines for Researching Sex/Gender in Human Health. Social Science & Medicine, 74, 1817-1824.

Tannenbaum, C., Ellis, R., Eyssel, F., Zou, J., Schiebinger, L. (2019). Sex and gender analysis improves science and engineering. Nature, 575(7781), 137-146.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2014), Evaluation of Sex-Specific Data in Medical device Clinical Studies. Washington, D.C.