Sex, Gender, & Intersectional Analysis

Case Studies

- Science

- Health & Medicine

- Chronic Pain

- Colorectal Cancer

- Covid-19

- De-Gendering the Knee

- Dietary Assessment Method

- Gendered-Related Variables

- Heart Disease in Diverse Populations

- Medical Technology

- Nanomedicine

- Nanotechnology-Based Screening for HPV

- Nutrigenomics

- Osteoporosis Research in Men

- Prescription Drugs

- Systems Biology

- Engineering

- Assistive Technologies for the Elderly

- Domestic Robots

- Extended Virtual Reality

- Facial Recognition

- Gendering Social Robots

- Haptic Technology

- HIV Microbicides

- Inclusive Crash Test Dummies

- Human Thorax Model

- Machine Learning

- Machine Translation

- Making Machines Talk

- Video Games

- Virtual Assistants and Chatbots

- Environment

Haptic Technology: Analyzing Gender

The Challenge

Engineers are designing new ways to communicate touch virtually through haptic devices. This raises questions about how touch should be employed in robotics. Should robot touch follow human conventions? Can touch between a human and a robot or mediating haptic device have the same meaning as it does between two humans?

Methods: Analyzing Gender

Research into human/robot touch is in its infancy, and few studies have considered the gender of the human as it interacts with robot “gender” (as established by social cues—see Gendered Robots). Roboticists need to consider how gender figures into human/robot touch. Studies need to include: 1) representative numbers of men, women, and gender fluid individuals plus robots with different gender configurations; 2) disaggregated data by gender (men, women, gender diverse); and 3) analyzed results by gender. Analyzing gender human/robot interaction is crucial to building effective interactions.

Gendered Innovations

1. Understanding the Gender Dynamics of Touch Among Humans

2. Building Gender Appropriate Touch into Robots and Haptic Devices

Next Steps

1. Analyzing the Impact of Human Gender in Human/Robot Touch

2. Analyzing the Impact of Perceived Robot Gender in Human/Robot Touch

The Challenge

Social robots are entering our lives in healthcare, elderly care, teaching, and entertainment (Li et al. 2017). In these settings, robots interact and communicate with humans by following rules of appropriate social behaviors. Social touch is an important part of human non-verbal communication. Emotions such as anger, fear, and happiness can be accurately communicated by touch, and more complex emotions like envy can be communicated by people who are close, such as romantic couples (Hertenstein et al., 2006; 2009; Thompson & Hampton, 2011).

Engineers are designing new ways to communicate touch virtually through haptic devices. Van Erp and Toet argue that haptic interactions help humans bond with robots (2013). This raises questions about how touch should be employed in robotics. Should robot touch follow human conventions? Can touch between a human and a robot or mediating haptic device have the same meaning as it does between two humans?

Gendered Innovation 1: Understanding the Gender Dynamics of Touch Among Humans

How does gender factor into the equation of social touch? As engineers seek to reproduce human social touch as closely as possible, it is important to understand the strong (largely unwritten) rules of etiquette governing human social touch (van Erp & Toet, 2013). Affective touch is a subset of social touch that communicates either positive or negative emotions. When appropriate, affective touch can modulate physiological responses, increase trust and affection, establish bonds, and moderate behavior. When inappropriate, affective touch can induce fear and repulsion (van Erp & Toet, 2015; Burleson et al., 2018). Here we focus specifically on how affective touch among humans varies with gender, keeping in mind that gender norms differ with intersecting factors, such as ethnicity and age.

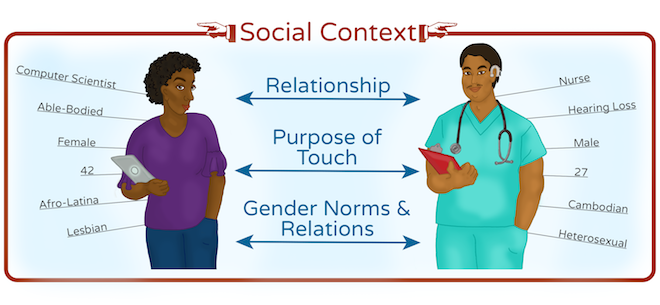

The social aspects of touch lie in the interaction between two humans. Each human is made up of different social characteristics; these include gender, age, educational background, etc. Click on the highlighted elements in Figure 1 to see how the meaning of touch between humans depends on: 1) the overall social context in which humans touch; 2) the relationship between the people touching; 3) the purpose of the touch; and 4) the broader gender norms & relations governing social interaction in particular cultures.

Figure 1. Touch between humans depends on who the person is in terms of gender, age, occupation, ethnic background, education, language, culture, ability, etc. It also depends on the social context within which a touch takes place—for example, at work or at home—and the gender norms governing social interactions in that space. Touch is governed by the purpose of the touch, gender relations between individuals, and their social relationship.

Next Steps in Studying Human/Human Touch

Studies of human social touch show that participants’ age, gender identity, and cultural backgrounds—as well as social context and purpose of the touch—all change touching behavior and response. To date, most studies analyze binary gender, i.e., men and women, with the assumption that people are heterosexual. We recommend that studies be expanded to consider gender-diverse individuals, including diverse sexual orientation, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, asexual (LGBQA) or diverse gender, such as transgender, genderqueer, or gender fluid.

Gendered Innovation 2: Building Gender Appropriate Touch into Robots and Haptic Devices

Some dimensions of human social touch may translate to human/robot interactive touch. Three aspects of human/robot touch will be considered here: 1) human touch mediated by haptic devices, 2) humans touching robots, 3) robots touching humans.

Human Touch Mediated by Haptic Devices

In many instances, haptic technologies aim to reproduce certain effects of human/human social touch at a distance. Researchers argue that mediated touch should mimic interpersonal human touch. Yohanan has cataloged 30 different haptic prototypes that use force, vibration, and temperature to mimic different human sensations, including a hug and a handshake (Yohanan & MacLean, 2012). Examples of such devices include The Hug, Thermal Hug, HotHands, POKE, etc. (for a list see Huisman, 2017, 396).

Humans Touching Robots

Etiquette for humans touching robots tend to follow human/human interaction, including gender conventions. For example, in one experiment in which participants were asked to “clean” virtual dirt particles from a virtual person, subjects of both genders used less force with female representations than male representations. They also used more force on the person’s torso than on their face (Bailenson & Yee, 2008, 167).

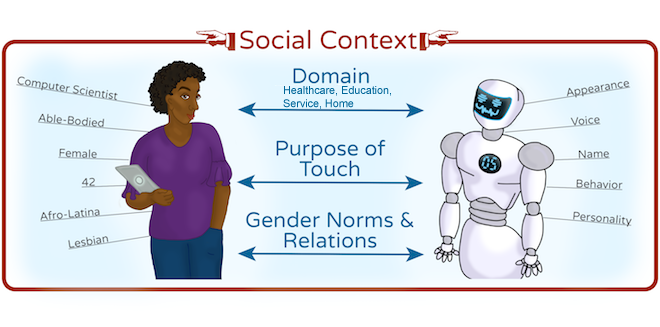

Figure 2. Touch between human and robot depends on who the human is and the domain in which the robot serves—for example, healthcare, service, education, etc. Responses to touch are governed by the purpose of the touch. What has not been studied is the interaction between human gender and perceived robot gender (see Gendering Social Robots).

Importantly, norms governing access to specific body regions is similar for humans and robots. In one study, 31 participants (16 female, 15 male) were asked to touch or point to anatomical regions on a humanoid robot. Participants were told they were engaged in an interactive anatomy lesson. The robot used was the 23-inch NAO, which is made of white plastic with various accent colors. Participants had increased physiological responses (electrodermal arousal) when asked to touch the robot’s buttocks or genitals and less when asked to touch accessible regions, such as its hands and feet. Although the experimenters recruited nearly half men and women, the authors did not analyze sex-disaggregated data (Li et al., 2017). The robot used has no perceivable sex or gender apart from the colored areas (in personal communication we learned that the accents are gray, which we interpret as gender neutral). Participants were prompted by NAO to touch them with a synthesized voice. We were unable to evaluate the voice for gender cues.

Importantly, norms governing access to specific body regions is similar for humans and robots. In one study, 31 participants (16 female, 15 male) were asked to touch or point to anatomical regions on a humanoid robot. Participants were told they were engaged in an interactive anatomy lesson. The robot used was the 23-inch NAO, which is made of white plastic with various accent colors. Participants had increased physiological responses (electrodermal arousal) when asked to touch the robot’s buttocks or genitals and less when asked to touch accessible regions, such as its hands and feet. Although the experimenters recruited nearly half men and women, the authors did not analyze sex-disaggregated data (Li et al., 2017). The robot used has no perceivable sex or gender apart from the colored areas (in personal communication we learned that the accents are gray, which we interpret as gender neutral). Participants were prompted by NAO to touch them with a synthesized voice. We were unable to evaluate the voice for gender cues.

Robots Touching Humans

Does etiquette for robots touching humans tend to follow human/human interaction, including gender conventions? Or do other rules apply? Research into robot-initiated touch is in its infancy, and few studies have considered the gender of the participant in the interaction with robot “gender” (as established by social cues). HRI experts caution the effective robot-initiated touch will depend on all the dimensions of the interaction that influence the effectiveness of human/human touch, such as the appearance and behavior of the robot, the user’s personality, including gender, the social context of the interaction, etc. (Willemse et al., 2017).

Robot-initiated touch will be crucial in areas such as nursing care. In an experiment at Georgia Tech, researchers programmed a robotic caregiver to touch and wipe subjects’ forearms. People responded more positively when the touch was instrumental, i.e., to clean the person’s skin, than when it was affective, i.e., to comfort the person (Chen et al., 2011). The experiment used equal numbers of men and women, but an analysis of gender differences in participant response was not reported.

Conclusion

As we have seen above human/human touch is complex, dependent on the overall social context in which touching occurs, the relationship— or degree of familiarity—between the people touching, the purpose of the touch, and gender norms. While well understood in human/human touch, gender has yet to be thoroughly examined in human/robot touch.

Next Steps

- 1. Analyzing the impact of human gender in human/robot touch.: Although most studies we reviewed were designed to include equal numbers of men and women, few: 1) disaggregated data by gender (whether the human is a man, woman, or gender fluid); or 2) analyzed results by gender. Reporting aggregated summaries for men and women may lead to flawed conclusions. For example, in a study of eight emotions, Hertenstein et al. (2009) reported that men and women were able to effectively communicate these emotions by touch. When they reanalyzed their data by sex in 2011, however, they found that only pairs of women touching women were able to effectively communicate happiness. Similarly, sympathy was effectively communicated only when one partner of the pair was a woman, and anger only when one partner of the pair was a man (2011). Analyzing gender in this instance was crucial to understanding the full implications of their results.

- 2. Analyzing the impact of perceived robot gender in human/robot touch. We know of no study that controlled for the perceived gender of the robot used or provided an analysis of perceived robot gender as it interacts with human gender. As robots are increasingly enter our lives, these analyses will be important for effective and safe collaborations between humans and robots.

Works Cited

Bailenson, J. N. & Yee, N. (2008). Virtual Interpersonal Touch: Haptic Interaction and Copresence in Collaborative Virtual Environments. International Journal of Multimedia Tools and Application 37(1), 5-14..

Bailenson, J. N., Yee, N., Brave, S., Merget, D., & Koslow, D. (2007). Virtual Interpersonal Touch: Expressing and Recognizing Emotions Through Haptic Devices. Human-Computer Interaction 22(3), 325-353.

Burleson, M. H., Roberts, N. A., Coon, D. W., & Soto, J. A. (2018). Perceived Cultural Acceptability and Comfort with Affectionate Touch: Differences between Mexican Americans and European Americans. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 0265407517750005.

Cabibihan, J. J., & Chauhan, S. S. (2017). Physiological Responses to Affective Tele-Touch During Induced Emotional Stimuli. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, 8(1), 108-118.

Cramer, H., Kemper, N., Amin, A., & Evers, V. (2009. The effects of robot touch and proactive behaviour on perceptions of human-robot interactions. In Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), 2009 4th ACM/IEEE International Conference on (pp. 275-276). IEEE.

Dibiase, R. & Gunnoe, J. (2004). Gender and Culture Differences in Touching Behavior. The Journal of Social Psychology 144(1), 49-62.

Evans, J. A. (2002). Cautious Caregivers: Gender Stereotypes and the Sexualization of Men Nurses’ Touch. Journal of Advanced Nursing 40(1), 441-448.

Gallup News (17 January 2017). http://news.gallup.com/poll/201731/lgbt-identification-rises.aspx

Haans, A., de Nood, C., & Ijsselsteijn, W.A. (2007). Investigating Response Similarities between Real and Mediated Social Touch: A First Test. CHI'07 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems,pp. 2405-2410.

Hall, J. A. & Veccia, E. M. (1990). More “Touching” Observations: New Insights on Men, Women, and Interpersonal Touch. Journal of Personality and Social Pscyhology 59(6), 1155-1162.

Hertenstein, M. J., Keltner, D., App, B., Bulleit, B. A., & Jaskolka, A. R. (2006). Touch Communicates Distinct Emotions. Emotion 6(3), 528-533.

Hertenstein, M. J., Holmes, R., McCullough, M., & Keltner, D. (2009). The Communication of Emotion via Touch. Emotion 9(4), 566-573.

Heslin, R., Nguyen, T. D., & Nguyen, M. L. (1983). Meaning of Touch: The Case of Touch from a Stranger or Same Sex Person. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 7, 147-157.

Huisman, Gijs. (2016). Social Touch Technology: A Survey of Haptic Technology for Social Touch. IEEE Transactions on Haptics. 10(3), 392-408.

Kosnar, Petr. (2012). Gender Differences in Same and Opposite Sex Mediated Social Touch: Affective Responses to Physical Contact in a Virtual Environment. Masters Thesis, Eindhoven. Adapted from Heslin, R., Nguyen, T. D., & Nguyen, M. L. (1983). Meaning of touch: The case of touch from a stranger or same sex person. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 7, 147-157, reprinted with permission.

Li, J. & Ju, W. (2017). Touching a Mechanical Body: Tactile Contact with Intimate Parts of a Humanoid Robot of Physiologically Arousing. Journal of Human-Robot Interaction 6(3), 118–130.

Major, B., Schmidlin, A. M., & Williams, L. (1990). Gender Patterns in Social Touch: The Impact of Setting and Age. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 58(4), 634-643.

Nilsen, W. J. & Vrana, S. R. (1998). Some Touching Situations: The Relationship Between Gender and Contextual Variables in Cardiovascular Responses to Human Touch. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 20(4): 270-276.

Remland, M. S., Jones, T. S., & Brinkman, H. (1995). Interpersonal Distance, Body Orientation, and Touch: Effects of Culture, Gender, and Age. The Journal of social psychology, 135(3), 281-297.

Suvilehto, J. T., Glerean, E., Dunbar, R. I. M., Hari, R., & Nummenmaa, L. (2015). Topography of Social Touching Depends on Emotional Bonds between Humans. PNAS 112(45), 13811-13816. Copyright (2015) National Academy of Sciences. PNAS does not require permission to reuse images for noncommercial and educational purposes.

Suzuki, K., Yokoyama, M., Kinoshita, Y., Mochizuki, T., Yamada, T., & Sakurai, S. (2016). Enhancing Effect of Mediated Social Touch between Same Gender by Changing Gender Impression. Proceedings of the 7th Augmented Human International Conference 2016.

Thompson, E. H. & Hampton, J.A. (2011). The Effect of Relationship Status on Communicating Emotions Through Touch. Cognition & Emotion 25(2), 295-306.

Tremblay, L., Roy-Vaillancourt, M., Chebbi, B., Bouchard, S., Daoust, M., Dénommée, J., & Thorpe, M. (2016). Body Image and Anti-Fat Attitudes: An Experimental Study Using a Haptic Virtual Reality Environment to Replicate Human Touch. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 19(2), 100-106.

Van Erp, J. B., Kyung, K. U., Kassner, S., Carter, J., Brewster, S., Weber, G., & Andrew, I. (2010, July). Setting the Standards for Haptic and Tactile Interactions: ISO’s Work. In International Conference on Human Haptic Sensing and Touch Enabled Computer Applications (pp. 353-358). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Van Erp, J. B., & Toet, A. (2013, September). How to Touch Humans: Guidelines for Social Agents and Robots that Can Touch. In Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction (ACII), 2013 Humaine Association Conference on (pp. 780-785). IEEE.

Willemse, C. J. A. M, Toet, A., & van Erp, J. B. F. (2017). Affective and Behavioral Responses to Robot-Initiated Social Touch: Toward Understanding the Opportunities and Limitations of Physical Contact in Human-Robot Interaction. Frontiers in ICT 4:12. doi: 10.3389/fict.2017.00012.

Willis, F. N., & Reeves, D. L. (1976). Touch Interactions in Junior High Students in Relation to Sex and Race. Developmental Psychology, 12(1), 91.

Social robots are entering our lives in healthcare, elderly care, teaching, and entertainment. In these settings, robots interact and communicate with humans by following rules of appropriate social behaviors. Social touch is an important part of human non-verbal communication. Emotions such as anger, fear, and happiness can be accurately communicated by touch, and more complex emotions like envy can be communicated by people who are close, such as romantic couples.

Research into human/robot touch is in its infancy, and few studies have considered the gender of the human as it interacts with robot "gender" (established by social cues—see Gendered Robots). Analyzing gender human/robot interaction is crucial to building effective interactions.

Engineers are designing new ways to communicate touch virtually through haptic devices. This raises questions about how touch should be employed in robotics. Should robot touch follow human conventions? Can touch between a human and a robot or mediating haptic device have the same meaning as it does between two humans?

Gendered Innovations

1. Understanding the gender dynamics of touch among humans

2. Building gender appropriate touch into robots and haptic devices

Next Steps

1. Analyzing the impact of human gender in human/robot touch.

2. Analyzing the impact of perceived robot gender in human/robot touch