Identify problem

Identify problem

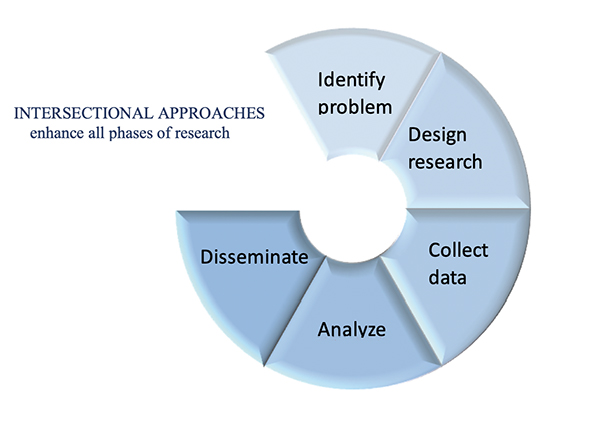

Intersectional approaches may be relevant in any study involving human subjects. While sex and gender are important concepts to consider (see Analyzing Sex; Analyzing Gender), they shape and are shaped by other socio-political dimensions. The way the research problem is formulated will determine which intersecting dimensions and factors are required for analysis.

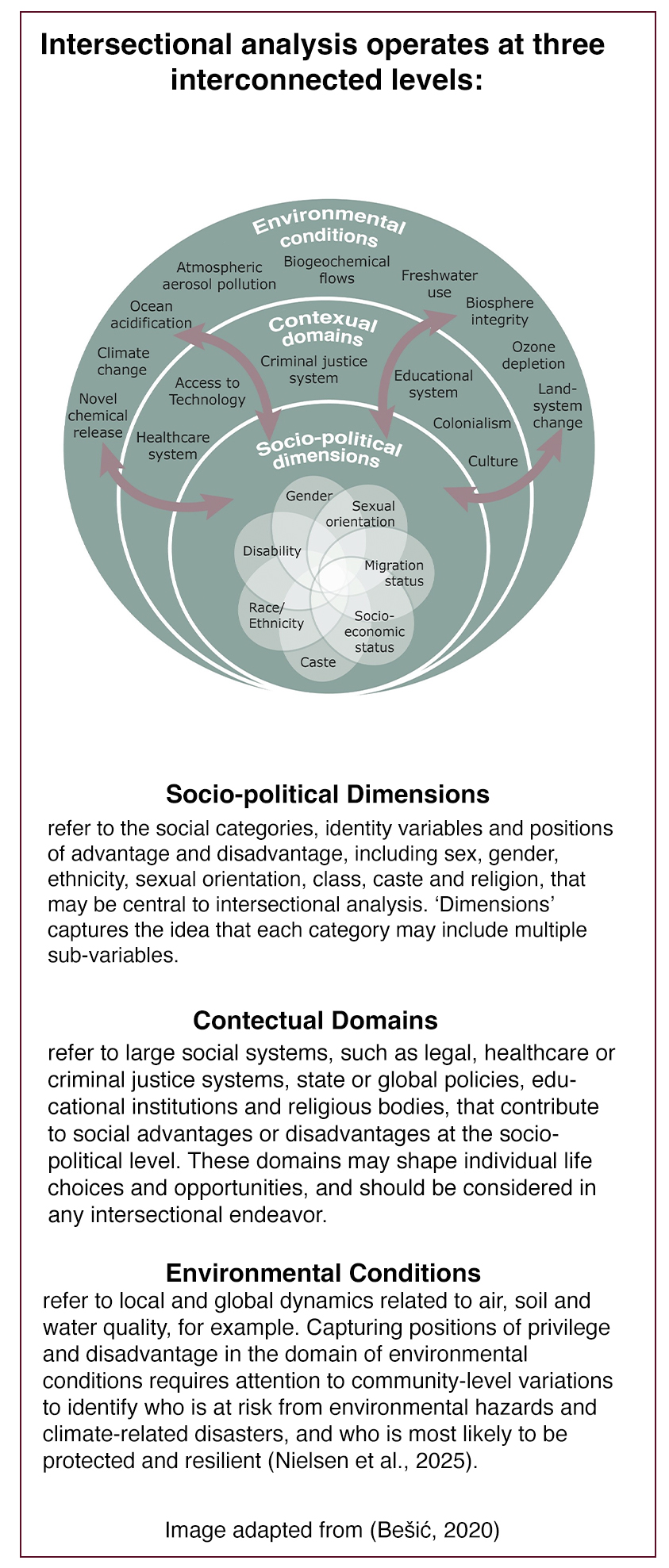

Before beginning a study, researchers should conduct systematic literature searches to identify factors and categories of potential relevance (Hankivsky, 2014). Analysis may consider three interconnected levels: socio-political dimensions, contextual domains, and environmental conditions (see box). Intersectionality always considers the compounded effects of two or more socio-political dimensions, such as gender, race, socio-economic status, disabilities, sexuality, geographic location, etc. (see Case Study: Facial Recognition). Intersectional analysis will also often consider the contextual domains or systems of power that shape and are shaped by people’s life experiences, opportunities, and choices in different ways. These may include societal, institutional and community-level circumstances (e.g. laws, policies, healthcare providers, school systems, law enforcement, religious institutions, crime rates) (see Case Study: Population and Climate Change).

Finally, intersectional analysis may examine environmental factors, such as air, soil, and water quality, and how they contribute to inequalities at the socio-political level. A focus on environmental factors, for example, enables a better understanding of the differential impacts of products and policies across geographical locations and social communities (see Case Study: Sustainable Fashion; Abi Deivanayagam et al., 2023).

From the outset, researchers will have to consider whose practical knowledge or experience is relevant to the project. Involving diverse groups of research subjects or potential end users in the research process (from problem formulation to research design) may sharpen the intersectional analysis and lead to more inclusive solutions (see Method: Co-Creation and Participatory research).

Intersectional research should be designed to illuminate interdependencies across socio-political dimensions, contextual domains, and environmental conditions. Intersectional statistical methods are usually multiplicative, not additive, implying a focus on compounded effects of different but interdependent categories and contexts. Determine which methods (qualitative, quantitative or mixed-method) are best suited for examining the intersecting variables of relevance to your project. Qualitative approaches (e.g., focus groups, document analysis, interviews and observations) can provide detailed insights into the complex web of factors, processes and relationships that shape people’s identities, opportunities, and practices (Collins & Bilge, 2020; Abrahms et al., 2020). Quantitative methods (e.g., survey questionnaires, social-media data, product purchases and register data) allow the researcher to examine similarities and differences across groups and subgroups, and may reveal how such similarities and differences vary by social context and evolve over time (Guan et al., 2021; Else-Quest and Hyde, 2016). In mixed-method designs, qualitative methods may be deployed to explore which intersectional categories, factors and relationships to examine in a subsequent quantitative analysis. Qualitative methods, however, may also be used to obtain a deeper understanding of salient interactions and relationships identified in a preceding quantitative analysis. A quantitative analysis, for example, may reveal unexpected differences between women and men that cannot be explained by gender or socioeconomic status alone, such as women of high socioeconomic status having similar health outcomes to those of men of low socioeconomic status (Sen et al., 2010). In this case, a qualitative follow-up study may help tease apart the underlying processes and mechanisms that drive the observed differences and similarities.

Consideration should always be given to the potentially dynamic nature of the intersectional categories and contextual factors in focus. The importance of different categories and factors may vary by social context, and may change over time (Hankivsky, 2014). In quantitative research, such variations could be examined using geospatial analysis or longitudinal designs (Weber et al., 2019; Warner & Brown, 2011).

Finally, researchers using qualitative interviews or surveys should inspect their questions and categories for misguided or stereotypical assumptions before initiating the data collection. Extensive piloting and/or cognitive interviews with the target population may improve the study’s validity and reliability, and make data collection more effective. Collect dataIntersectional research requires detailed information on socio-political dimensions (such as sub-variables for sex, gender, class, and caste) and careful consideration of the contextual domains and environmental conditions that structure the data (D'ignazio & Klein, 2023). Treating sex assigned at birth as a proxy for gender identity, for example, risks properly assessing the experiences of minoritised identities. To remedy this shortcoming, researchers may adopt a two-step method in questionnaires that measures sex assigned at birth and self-reported gender identity separately (Magliozzi, 2016). Researchers may need to strategically oversample specific subgroups to ensure sufficient statistical power for intersectional analysis.

In quantitative research, calculate the minimum sample size required for each group included in your analysis to allow for meaningful statistical analysis (Rouhani, 2014). Strategic oversampling of some groups may be necessary to allow sufficient statistical power for cross-group comparisons and interaction analyses. Respondent-driven sampling (Heckathorn, 1997) and time-space sampling (MacKellar et al., 2007) can be used to recruit marginalized or hidden populations that are difficult to access through traditional sampling methods (Bowleg & Bauer, 2016). When considering human-environment interactions, research increasingly combines Satellite Earth Observation and georeferenced social science data to provide high resolution, longitudinal estimates of human population distributions, where needed (Bosco et al., 2017; Kugler, et al., 2019). Currently, only two global datasets, Gridded Population of the World (GPW) v4 and WorldPop, provide estimates by sex and age (Dahmm & Rabiee, 2020).

In qualitative research, the sample should be heterogeneous enough to capture the various intersecting positions of relevance to the research problem.

Analyze dataAn intersectional analysis seeks to illuminate the multiplicative effects of different but interdependent categories and factors.

Quantitative research should move beyond an additive focus on main effects (e.g. estimating separate effects for gender, race, and sexual orientation) to examine how the variables in focus intersect (Bauer, 2014; Hancock, 2007; Bowleg & Bauer, 2016; Evans et al., 2024). Multilevel models (e.g., hierarchical linear modelling) may be employed to tease out estimates at the intersection of multiple variables capturing socio-political dimensions (e.g., gender and sexual orientation and immigration status) that possibly vary across contexts (e.g., countries, regions, schools, hospitals or neighborhoods), and environmental conditions (e.g., air, soil, and water quality) (for details of these methods, see Nielsen et al., 2025).

Qualitative analyses will often be exploratory in nature and should offer rich descriptive accounts of the various categories, factors and processes that intersect to shape people’s identities, opportunities and practices in a given context (Hunting, 2014). Such an analysis should examine both commonalities and differences across categories and factors, and acknowledge within-group variations in experiences, viewpoints and behaviors. A multi-level approach, operationalized through a nested coding of the data material, may be used to explore how individual experiences and behaviors relate to broader group-level and contextual factors (Hankivsky, 2014).

Reporting and Disseminating resultsFor reporting guidelines, see Guidelines for Intersectional Analysis in Science and Technology: Implementation and Checklist Development (2025).

Reporting should specify the sample characteristics by gender, sex, and relevant intersecting variables and describe how information for each variable was obtained. To promote transparency, researchers should report all relevant outcomes of the intersectional analysis including inconclusive results. Be specific about which findings generalize broadly and which apply to specific populations, variables, or geographical or environmental locations.

When reporting the results of cross-group comparisons, provide information on the within-group variability and between-group overlap of the distributions. Be careful not to overemphasize differences between individuals or groups. Ensure that information on both differences and similarities is properly reported in the text, tables and figures, and that sensitivity to nuance is maintained throughout the report (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016; Cole, 2009).In quantitative research, statistical interactions (and effect-measure modification) should be reported in sufficient detail to enable readers to interpret the effect size and practical significance of the findings (Bauer, 2014; Knol & Van der Weele, 2012).

Given the close link between intersectionality and questions of power, privilege and inequality, it is important to situate the study findings in the context of the target populations’ particular institutional, community-level, and environmental circumstances (Hankivsky, 2014; Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016b).

Dissemination strategies should take into account the complexity of target audiences. Too often, researchers restrict their audience to academic peers. An intersectional approach helps sensitize the researcher to many other potential audiences.

When intersectional datasets are made open access, careful considerations about anonymity are warranted. For instance, “anonymized” data including demographic information on zip code, birth data, ethnicity and sex may offer sufficient information for others to de-anonymize the data (Sweeney, 2002).

Works Cited

Abrams, J. A., Tabaac, A., Jung, S., & Else-Quest, N. M. (2020). Considerations for employing intersectionality in qualitative health research. Social science & medicine, 258, 113138.

Abi Deivanayagam, T., English, S., Hickel, J., Bonifacio, J., Guinto, R. R., Hill, K. X., ... & Devakumar, D. (2023). Envisioning environmental equity: climate change, health, and racial justice. The Lancet, 402(10395), 64-78. Bauer, G. R. (2014). Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Social Science & Medicine, 110, 10-17. Bešić, E. (2020). Intersectionality: A pathway towards inclusive education? Prospects, 49(3), 111-122. Bosco, C., Alegana, V., Bird, T., Pezzulo, C., Bengtsson, L., Sorichetta, A., ... & Tatem, A. J. (2017). Exploring the high-resolution mapping of gender-disaggregated development indicators. Journal of The Royal Society Interface, 14(129), 20160825. Bowleg, L., & Bauer, G. (2016). Invited reflection: Quantifying Intersectionality. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(3), 337-341. Cole, E. R. (2009). Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist, 64(3), 170-180. Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2020). Intersectionality. John Wiley & Sons. Dahmm, H. & Rabiee, M. (2020). Leaving no one off the map: a guide for gridded population data for sustainable development. Data and Statistics (TReNDS) of the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network. D'ignazio, C. & Klein, L. F. (2023). Data feminism. MIT Press. Else-Quest, N. M., & Hyde, J. S. (2016). Intersectionality in quantitative psychological research: I. Theoretical and epistemological issues. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(2), 155-170. Evans, C. R., Borrell, L. N., Bell, A., Holman, D., Subramanian, S. V., & Leckie, G. (2024). Clarifications on the intersectional MAIHDA approach: A conceptual guide and response to Wilkes and Karimi (2024). Social Science & Medicine, 350, 116898. Guan, A., Thomas, M., Vittinghoff, E., Bowleg, L., Mangurian, C., & Wesson, P. (2021). An investigation of quantitative methods for assessing intersectionality in health research: A systematic review. SSM-population health, 16, 100977. Hancock, A. M. (2007). Intersectionality as a normative and empirical paradigm. Politics & Gender, 3(2), 248-254. Hankivsky, O. (2014). Intersectionality 101. The Institute for Intersectionality Research & Policy, SFU, 1-34. Heckathorn, D. D. (1997). Respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems, 44(2), 174-199. Hunting, G. (2014). Intersectionality-informed qualitative research: A primer. The Institute for Intersectionality Research & Policy, SFU, 1-20. Knol, M.J., VanderWeele, T.J., 2012. Recommendations for presenting analyses of effect modification and interaction. International Journal of Epidemiology, 41(2), 514-520. Kugler, T. A., Grace, K., Wrathall, D. J., de Sherbinin, A., Van Riper, D., Aubrecht, C., ... & Van Den Hoek, J. (2019). People and Pixels 20 years later: the current data landscape and research trends blending population and environmental data. Population and Environment, 41(2), 209-234. Landrigan, P. J., Raps, H., Cropper, M., Bald, C., Brunner, M., Canonizado, E. M., ... & Dunlop, S. (2023). The Minderoo-Monaco commission on plastics and human health. Annals of Global Health, 89(1), 23. MacKellar, D. A., Gallagher, K. M., Finlayson, T., Sanchez, T., Lansky, A., & Sullivan, P. S. (2007). Surveillance of HIV risk and prevention behaviors of men who have sex with men—a national application of venue-based, time-space sampling. Public Health Reports, 122(1_suppl), 39-47. Magliozzi, D., Saperstein, A., & Westbrook, L. (2016). Scaling up: Representing gender diversity in survey research. Socius, 2, 2378023116664352. Nielsen, M. W., Gissi, E., Heidari, S., Horton, R., Nadeau, K. C., Ngila, D., Noble, S. U., Paik, H. Y., Tadessa, G. A., Zeng, E. Y. Zou, J., & Schiebinger, L. (2025). Intersectional analysis for science and technology. Nature, 640(8058), 329-337. Rouhani, S. (2014). Intersectionality-informed quantitative research: A primer. The Institute for Intersectionality Research & Policy, SFU, 1-16. Schiebinger, L., Nielsen, M. W., Gissi, E., Heidari, S., Horton, R., Nadeau, K. C., Ngila, D., Noble, S. U., Paik, H. Y., Tadessa, G. A., Zeng, E. Y. Zou, J., & Marsh, J. (2025). Guidelines for Intersectional Analysis in Science and Technology: Implementation and Checklist Development. European Science Editing, 51, e162102. Sen, G., Lyer, A., & Mukherjee, C. (2010). A Methodology to Analyze the Intersections of Social Inequalities in Health. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 10(3), 397-415. Sweeney, L. 2002. K-Anonymity: A Model for Protecting Privacy. International Journal of Uncertainty, Fuzziness and Knowledge-based Systems, 10(5), 557–570. Warner, D. F., & Brown, T. H. (2011). Understanding how race/ethnicity and gender define age-trajectories of disability: An intersectionality approach. Social Science & Medicine, 72(8), 1236-1248. Weber, A. M., Cislaghi, B., Meausoone, V., Abdalla, S., Mejía-Guevara, I., Loftus, P., ... & Buffarini, R. (2019). Gender norms and health: insights from global survey data. The Lancet, 393 (10189), 2455-2468.