Sex & Gender Analysis

Case Studies

- Science

- Health & Medicine

- Chronic Pain

- Colorectal Cancer

- Covid-19

- De-Gendering the Knee

- Dietary Assessment Method

- Gendered-Related Variables

- Heart Disease in Diverse Populations

- Medical Technology

- Nanomedicine

- Nanotechnology-Based Screening for HPV

- Nutrigenomics

- Osteoporosis Research in Men

- Prescription Drugs

- Systems Biology

- Engineering

- Assistive Technologies for the Elderly

- Domestic Robots

- Extended Virtual Reality

- Facial Recognition

- Gendering Social Robots

- Haptic Technology

- HIV Microbicides

- Inclusive Crash Test Dummies

- Human Thorax Model

- Machine Learning

- Machine Translation

- Making Machines Talk

- Video Games

- Virtual Assistants and Chatbots

- Environment

Smart Energy Solutions: Intersectional Approaches

The Challenge

In the EU, buildings are responsible for approximately 40% of energy consumption and 36% of CO2 emissions. They are therefore the single largest energy consumer in Europe (EC, 2019). For climate change solutions, the world needs an effective energy transition. This energy transition depends, at least in part, on users’ acceptance of new technologies and services, and on robust public engagement in conceptualizing, planning, and implementing low carbon energy solutions. This case study analyses how to integrate gender and intersectional analysis into energy research and into the development, design and commercialization of energy products and services in order to maximize the adoption of new energy efficiency tools and technologies.

Method: Engineering Innovation Process

Energy efficiency tools and solutions need to work for everybody in order to support an effective energy transition. Although many energy-efficient technologies and products are available, they are often rejected by users in households, the public sector, and industry because they do not meet the values, motivations and needs of different user groups, which are shaped and influence by gender norms and different lifestyles. Redesigning the engineering process can lead to broader acceptance of energy efficiency tools and products.

Method: Intersectional Approaches

The energy debates often ignore the human factor. An intersectional approach is needed, one that recognizes people’s multiple, interdependent and overlapping axes of social identity, e.g. gender, socio-economic status and age. A single factor, such as gender, both shapes and is shaped by other social attributes such as age, ethnicity and socio-economic status. Together, these factors influence the life experiences of citizens engaging with the complex sociotechnical networks that constitute the energy system.

Gendered Innovations:

1. Designing Energy Efficiency Tools that Integrate Gender Perspectives: Redesigning the Engineering Innovation Process has led to new opportunities for environmental and economic solutions that can propel the energy transition by increasing users’ adoption of novel technologies.

2. Driving the Energy Transition by Taking an Intersectional Approach to Gender, Age and Socioeconomic Factors Energy researchers, companies, policy-makers, and researchers need to better understand the role that gender and other social, economic and demographic factors play in energy policy. Gender and intersectional analysis are required for effective and equitable energy technologies and policies.

Method: Engineering Innovation Process

Method: Intersectional Approaches

Gendered Innovation 1: Designing Energy Efficiency Tools that Integrate Gender Perspectives

Gendered Innovation 2: Driving the Energy Transition by Taking an Intersectional Approach to Gender, Age and Socioeconomic Factors

Conclusions

Next Steps

The Challenge

Over the past few decades, governments and intergovernmental agencies have set ambitious energy efficiency and reduction targets. For example, the EU’s Directive on Energy Efficiency sets a target of 32.5% increase in energy efficiency by 2030 (EP, EC, 2012 - 2012/27/EU; EP, EC, 2018 - 2018/2002). These targets are part of the United Nation’s global effort to ensure access to affordable, reliable and sustainable energy for all. The UN aims to substantially increase the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix by 2030, which will require expanding infrastructure and upgrading technology (UN, 2015).

Despite energy-efficient construction and smart home installations, energy targets for the EU building sector have not been met. Consumers are often blamed for not using the technologies correctly. At the same time, smart technologies are often complex and frustrating to users. To overcome these problems, engineers and design experts need to integrate user perspectives in the design of technologies for homes and public buildings.

This case study analyses how energy efficiency projects can integrate gender perspectives along with sensitivity to age, socioeconomic and other social factors into design. Getting it right for a broad user base will help realize the potential of smart technologies that support EU and global energy targets.

Gendered Innovation 1: Designing Energy Efficiency Tools that Integrate Gender Perspectives

Over the past decades, product developers have integrated user-centric perspectives to better meet user needs and expectations. The field of energy efficiency, however, has lagged behind.

Danfoss, an international manufacturer and service provider for energy-efficient smart heating solutions, experienced low sales figures for one of its new products. When looking at its customer base, the company realized that women should constitute 50% of their users, but they were, in fact, significantly under-represented. To address the problem, Danfoss teamed up with design-people, a Danish design agency, to investigate the values, motivations and needs of women in relation to technology.

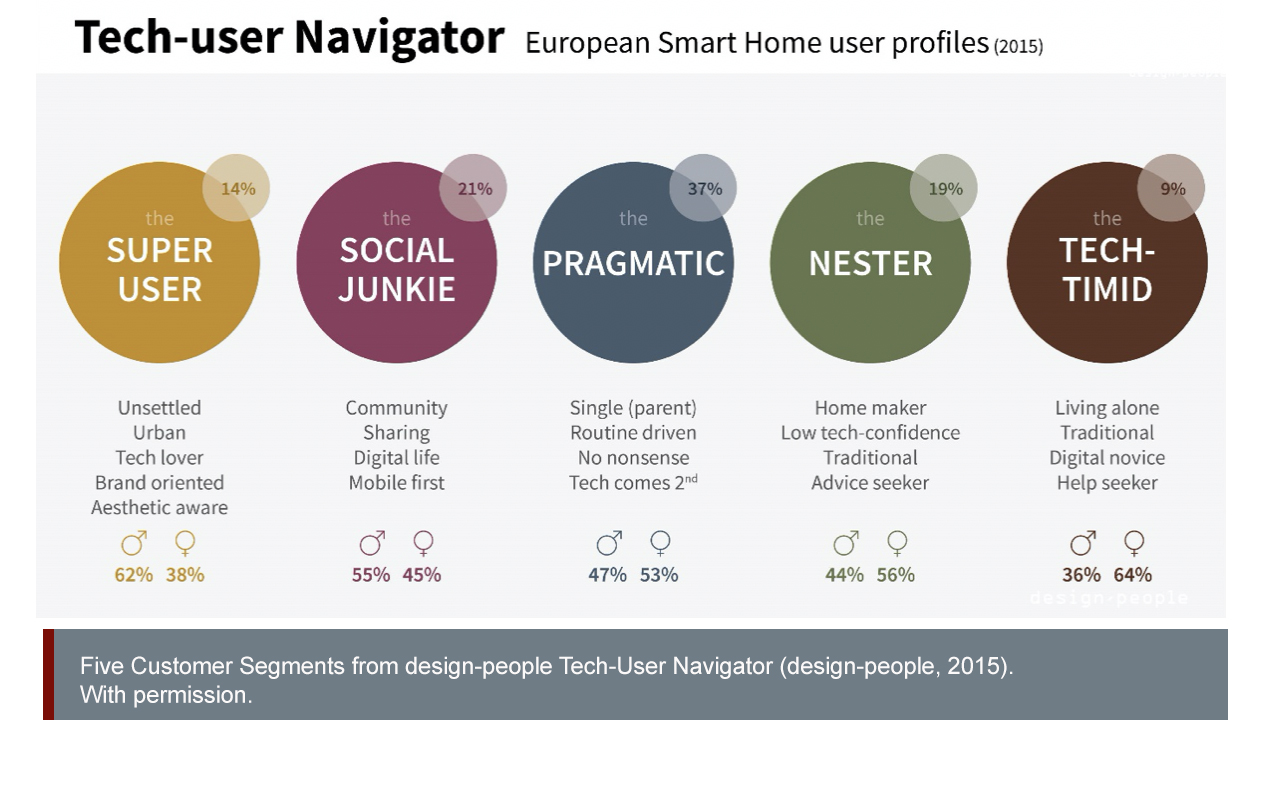

The agency used surveys to cluster users into five segments, characterized by different attitudes to technology.

The largest segment was characterized as “Pragmatic” tech-users (37%, finely balanced with 53% women and 47% men). Danfoss chose this group as the target for the company’s new entry-level smart thermostat. The company created a persona, named “Johanna,” to represent this group. A careful focus on Johanna’s preferences along the entire customer journey allowed the design and engineering team to create an award-winning user experience for their new Danfoss ECO thermostat (https://www.design-people.com/portfolio/danfoss-eco/). Two years after introduction, the sales figures of the new thermostat—a good proxy for user adoption—exceeded Danfoss’s expectations.

Method: Engineering Innovation Processes

1. Evaluating Past Innovation Practices

By analyzing the traditional engineering innovation process of Danfoss smart home appliances, the engineering team identified a lack of diversity in user perspectives as a problem. Without a clear focus on target personas, engineers and designers may unconsciously use themselves as a benchmark for the user experience.2. Building diverse development and design teams

The Danfoss case clearly demonstrates the advantages of including women and men with diverse attitudes to technology in the design process. Integrating a wide range of new and diverse perspectives will lead to further innovation. New research priorities and research questions can lead to new findings and innovative ideas (see Rethinking Research Priorities and Outcomes and Formulating Research Questions).3. Analyzing Users and Markets

User needs and behaviors can be identified through surveys, interviews, focus groups and direct observation. Engineers and designers can analyze gender by collecting quantitative survey data, as in the Danfoss example, or by observing user practices and learned behaviors. The best user research will include intersectional approaches to gender, ethnicity, age, socioeconomic status, etc.4. Obtaining User Input

In the Danfoss project, participatory research allowed designers to tap into users’ tacit knowledge (see Co-Creation and Participatory Research). User research revealed that women valued both easy temperature control and air quality control. The engineers had not considered air quality or the aesthetics of thermostat design in the product development, and they had not been confronted with different experiences with respect to the ease of use of their product.5. Evaluation and Planning

To improve the engineering innovation process, companies should assess the benefits and problems of current products and services. They should then transfer the lessons learned across other areas of the organization. Guidelines for the evaluation and planning of the engineering innovation process can be based on design-people and Rethinking Research Priorities and Outcomes.

Danfoss and design-people translated their research findings and principles into a more user-responsive indoor climate solution, i.e. including not only temperature but also air quality controls. They replaced the wall-mounted control panels with more discreet sensors controlled from tablets and smart phones. This allowed users to balance climate comfort and energy saving by controlling their heating system remotely.

In addition, Danfoss paid attention to air quality. The surface of the new thermostat and sensors ruptured into crystal patterns when air quality deteriorated, indicating that users should refresh the air.

Gendered Innovation 2: Driving the Energy Transition by Integrating an Intersectional Approach to Gender, Age and Socioeconomic Factors

To tackle the energy transition, the European Union-funded H2020 research project ENTRUST (Energy System Transition Through Stakeholder Activation, Education and Skills Development) focused on the social dimensions of the energy system. This project introduced an intersectional approach to understand how gender, age and socioeconomic status impact the transition to a low carbon energy system. ENTRUST focused on attitudes to different energy technologies, including energy sources: fossil fuels, renewables and nuclear energy. Other projects might use different social analytics, such as sexuality, gender-diverse individuals, religion, etc. Each project must hypothesize the social factors most relevant to its goals.

ENTRUST analyzed the daily domestic routines of users from six European communities that differed socially, economically and geographically. The intersectional approach analyzed gender, socio-economic status and age as these relate to energy practices. The results showed that culture, age or poverty may have more impact on energy use than gender—see also Case Study: Climate

Laundry, for example, is a gendered issue. Men often leave laundry to women or to a laundry service, and thus do not mention it when describing their daily routines (Dunphy et al., 2018. D3.2, p.77). Income also impacts laundry practices. One low-income participant (male), conscious of the high cost of electricity, paid extra to buy an ecological washing machine. Two other low-income participants (female) did laundry at off-peak times when electricity rates were lower or simply did less washing to reduce costs. It is important to consider both gender and socioeconomic status as intersecting factors in order to forge solutions that cater for all social groups (Dunphy et al., 2018. D3.2, pp.56-57).

Another example is cooking, which neither women nor men typically mention as energy intensive. In lower-income households, however, both women and especially men have developed specific practices to reduce costs when preparing hot meals (Dunphy et al., 2018. D3.2, pp.62-63).

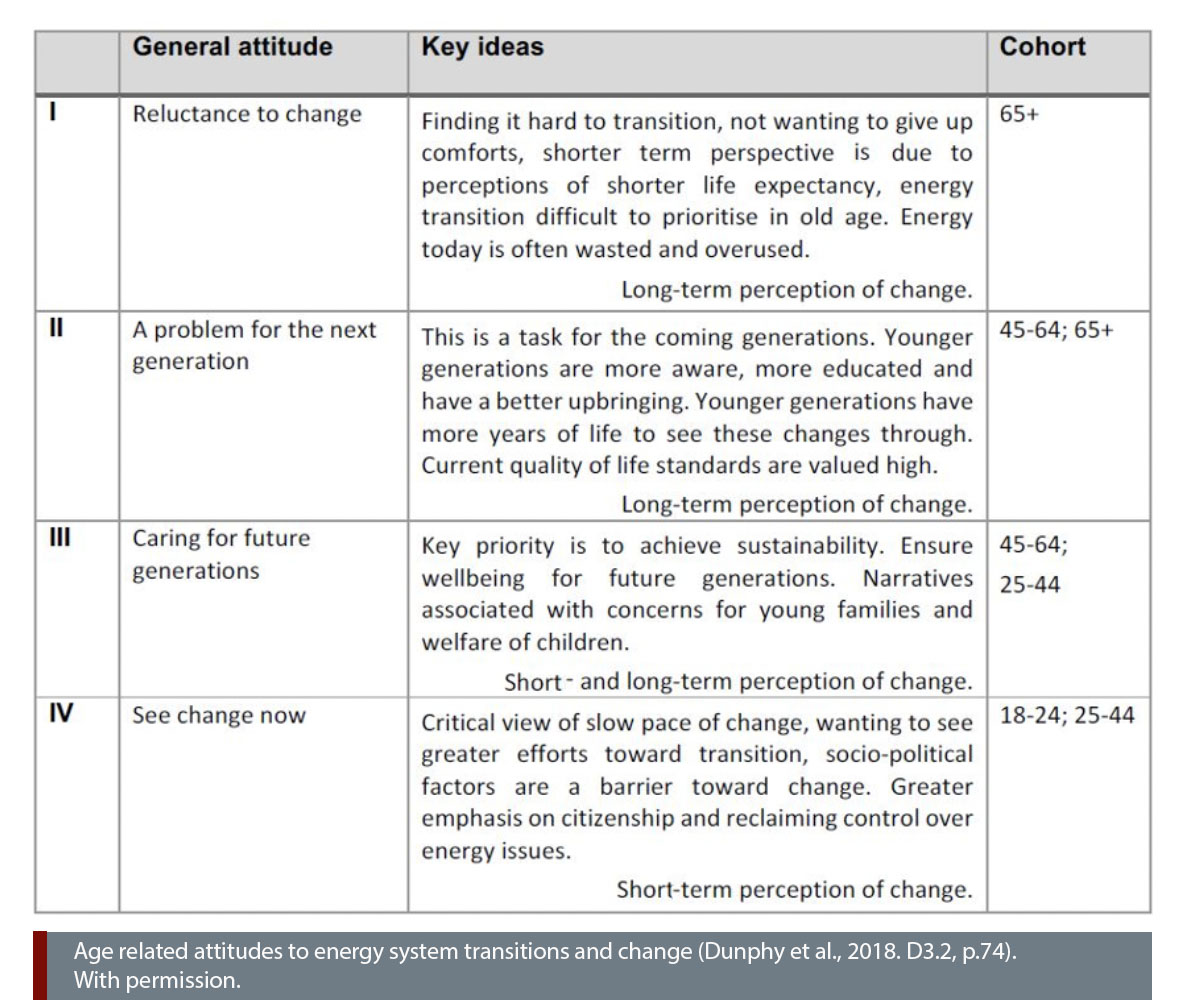

Further, analyses show that older generations consider today’s availability of electricity and energy as a privilege, not a given. Lifestyle changes which could reduce energy consumption are less appealing to this group (over 65). For different cohorts, different short-term and long-term perceptions of change will affect their choice of energy source and service, as shown below, and intersect with other sociodemographic factors such as gender or socio-economic status.

Based on this research, ENTRUST developed new approaches to public policy, business innovation and community engagement. Twelve business models emerged for energy production and supply, urban environments and shared mobility, with a particular focus on public-private partnerships and community-based approaches. Other approaches included Public Private Modularized Building (PPMB), Community-based energy service companies (ESCOs), Peer-to-Peer Community Energy Trading (P2P-CETs) or Free-floating Car Sharing with an Operational Area (FCSOA) (Dunphy, Lennon, et al., 2018. D6.4).

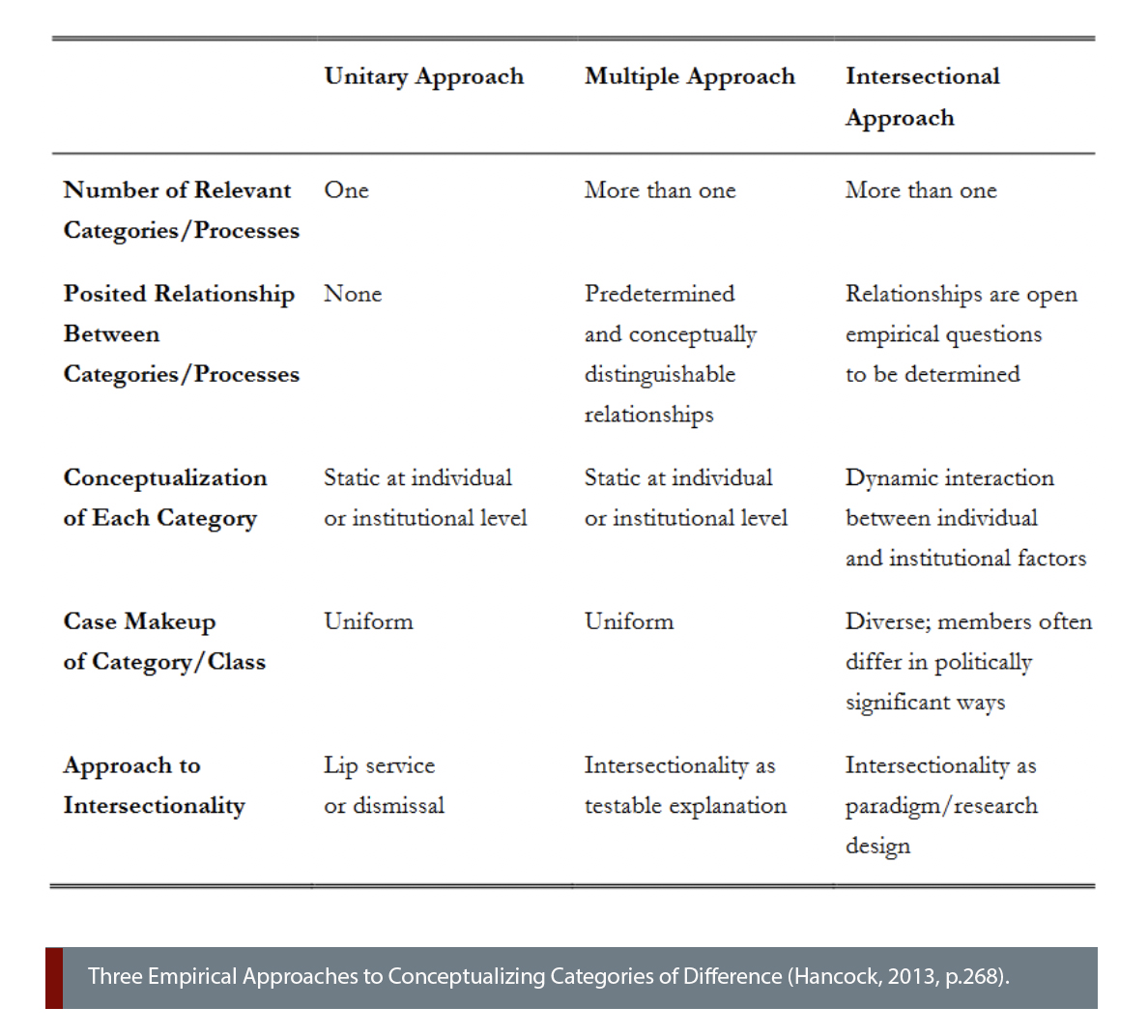

Method: Intersectional Approaches to the Energy Sector

The ENTRUST project applies the concept of intersectionality to highlight how various sociodemographic factors interact. The project seeks to understand how energy attitudes and behavior are shaped by social attributes, such as gender, age and socio-economic status. The teams were particularly interested in understanding the life experiences of citizens engaging with the complex socio-technical networks that constitute the energy system. This intersectional approach allows for a more differentiated analysis of energy-related attitudes and behaviors. The following table demonstrates the benefits of an intersectional analysis in comparison to other more restricted approaches (Hancock, 2013).

Conclusions

The case study provides clear examples of how to improve research and innovation processes relevant to energy efficiency measures. It also shows how to improve new and existing technologies and enhance their market acceptance by integrating gender and diversity perspectives into development, design and testing.

1. To reach the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for energy infrastructure and technology, it will be important to implement gender and intersectional analyses as a cross-cutting issue. This will enhance the acceptance and usability of energy products and services, and stimulate the market uptake of energy solutions.

2. We recommend regular and systematic audits to evaluate energy systems and solutions from a gender perspective and an intersectional perspective.

Works Cited

Tech-User Navigator. (2015). design-people. (a href="https://www.design-people.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Tech-user_Navigator_Light_9-17b.pdf"> https://www.design-people.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Tech-user_Navigator_Light_9-17b.pdf

Dunphy, N., Lennon, B., Sanvicente, E., Tart, S., Kielmanoicz, D., & Morrissey, J. (2018). Innovative Business Models to Foster Transition. D6.4 of the ENTRUST H2020 project.

Dunphy, N., Revez, A., Gaffney, C., Lennon, B., Aguilo, A. R., Morrissey, J., & Axon, S. (2018). Intersectional analysis of energy practices. Deliverable 3.2 of the ENTRUST H2020 project. Cork.

Dunphy, N., Revez, A., Gaffney, C., & Lennon, B. (2018). Intersectional Analysis of Perceptions an Attitudes Towards Energy Technologies. Deliverable 3.3 of the ENTRUST H2020 project. Cork.

Dunphy, N., Revez, A., Gaffney, C., Lennon, B., Sanvicente, E., Landini, A., & Morrissey, J. (2018). Synthesis of socio-economic, technical, market and policy analyses. Deliverable 3.4 of the ENTRUST H2020 project. Cork.

ENTRUST: Energy System Transition Through Stakeholder Activation, Education and Skills Development.

European Commission (EC). (2019). Energy performance of buildings directive. https://ec.europa.eu/energy/en/topics/energy-efficiency/energy-performance-of-buildings/energy-performance-buildings-directive#facts-and-figures

European Commission (EC). (2019). Orientations towards the first Strategic Plan for Horizon Europe. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/research_and_innovation/strategy_on_research_and_innovation/documents/ec_rtd_orientations-he-strategic-plan_122019.pdf

European Parliament (EP), Council of the European Union (EC). (2012). Directive 2012/27/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2012 on energy efficiency, amending Directives 2009/125/EC and 2010/30/EU and repealing Directives 2004/8/EC and 2006/32/EC Text with EEA relevance. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2012/27/oj

European Parliament (EP), Council of the European Union (EC). (2018). Directive (EU) 2018/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 amending Directive 2012/27/EU on energy efficiency. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2018/2002/oj

Fraune, C. (2016). The politics of speeches, votes, and deliberations: gendered legislating and energy policy-making in Germany and the United States. Energy Research & Social Science, 19, 134-141.

Hancock, A. M. (2013). Empirical intersectionality: a tale of two approaches. UC Irvine Law Review, 3, 259-296. https://www.law.uci.edu/lawreview/vol3/no2/hancock.pdf

Henwood, K., & Pidgeon, N. (2015). Gender, ethical voices and UK nuclear energy policy in the post Fukushima era. In B. Tahbi & S. Roeser (Eds.), The Ethics of Nuclear Energy, pp. 67-84. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lennon, B., Dunphy, N., Sanvicente, E., Hillman, J., Morrissey, J. (2018). Energy Management Approaches for Sustainable Communities. D5.3 of the ENTRUST H2020 project.

United Nations (UN). (2015). Sustainable Development Goals: Goal 7: Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/energy/

To solve climate change, the world needs to transition to efficient energy. Energy solutions depend, at least in part, on users’ acceptance of new technologies and services. This case study analyses how energy efficiency projects can—early in the design process—integrate gender perspectives along with sensitivity to age, socioeconomic status, and other social factors. Getting it right for a broad user base will help support the UN Sustainable Development Goal # 13—Climate Action.

The Danish multinational Danfoss experienced low sales figures for one of its new home-heating products—a smart thermometer. When looking at its customer base, the company realized that women should constitute 50% of their users, but were, in fact, significantly underrepresented. To address this issue, the company used surveys to cluster users into five segments, characterized by different attitudes toward technology.

The largest segment was characterized as “Pragmatic” tech-users (37%, nicely balanced with 53% women and 47% men). Danfoss chose this group as the target for its new entry-level smart thermostat. Two years later, the sales figures of the new thermostat—a good proxy for user adoption—exceeded Danfoss’s expectations.